AUSTRALIAN ART

Toledo museum to offer distinct, dazzling exhibit

Aboriginal works contemporary, captivating

4/10/2013

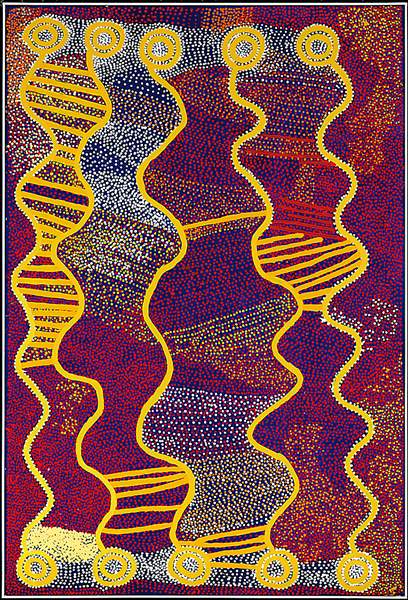

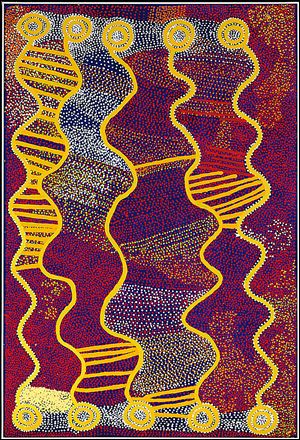

The exhibit includes this piece by Shorty Jangala Robertson, an acrylic on canvas from 2007.

TOLEDO MUSEUM OF ART

The exhibit includes this piece by Shorty Jangala Robertson, an acrylic on canvas from 2007.

Brian Kennedy has slept outside under Australia’s infinite blanket of brilliant stars, walked the continent’s desiccated desert floors, and traveled its rough back roads.

So it is understandable when the director of the Toledo Museum of Art became animated and broke into a little dance shuffle while describing how a piece of art could be interpreted as he showed a visitor a preview of Crossing Cultures: The Owen and Wagner Collection of Contemporary Aboriginal Australian Art at the Hood Museum of Art, the fascinating exhibition that opens with a semiprivate reception today at the museum.

The display, which will be available to the general public for free at 10 a.m. Friday and run until July 14, is educational and strikingly beautiful, exploring a culture and art movement that Americans will find both familiar and alien. Analogies to the European settlers’ treatment of the natives who lived in North America are inescapable. But the Australian experience is unique and should be taken on its own terms.

Crossing Cultures also questions conventional definitions of art. For the uninitiated, the idea of “Aboriginal art” most likely conjures images of relatively dusty works that stretch into antiquity, but the reality of these paintings and sculptures is much different, Mr. Kennedy said.

“It is challenging for a lot of Western museums to accept this art into their museums, to consider it contemporary,” he said.

“So the dichotomies at work are those between Western understanding of art and artifact ... and then the dichotomy between our notion of tradition and what is contemporary. So in the West, say America, we have difficulty with the idea of folk art and, can folk art be contemporary? And I would say, of course it can.”

‘It changed our lives’

The exhibition’s journey to Toledo is a result of a confluence of circumstances that spans the globe, starting with the fact that from 1997 to 2004, Mr. Kennedy was director of the National Gallery in Australia, which afforded him numerous opportunities to explore the continent’s rich art history.

The other key players are Will Owen and Harvey Wagner, a pair of collectors who work at the University of North Carolina. In 1988, they were introduced to Aboriginal Australian art by chance while visiting other galleries in New York.

Museum director Brian Kennedy said the exhibit is ‘loaded, powerful.’

Instantly, they were smitten.

“I mean this literally: it changed our lives,” Mr. Owen said in a telephone interview. “Two years later, we were on a plane to Australia, and we bought our first painting. It has been a passion for 23 years.”

They began collecting various works from Aboriginal artists, amassing a large collection of pieces from what the late art critic Robert Hughes called the “last great art movement of the 20th century.”

As their collection grew, they began looking for someplace to house it and, as Mr. Owen writes in the catalog created for Crossing Cultures: “to find a home for the collection in an institution of higher education where it could further the study, appreciation, and understanding of Aboriginal art and culture.”

Enter Mr. Kennedy, who by the mid-2000s was director of the Hood Museum of Art at Dartmouth in Hanover, N.H.

After meeting with him and exploring their common interests, Mr. Wagner and Mr. Owen donated their works to the museum, which curated a show of Aboriginal women’s art. Dartmouth also organized classes and various seminars to study the works.

Beautiful and challenging

An important component of the Toledo exhibit is educational. The first panel of information for visitors features a map of the continent and text about its history and that of the Aboriginal people. While Australia is roughly the same size as the United States, the country has just 23 million people, about 550,000 of whom are of Aboriginal descent.

Its historic treatment of the natives is every much as shameful as that of this country. When the continent was settled by the British in 1788, 1 million Aboriginal people lived there. That population was decimated to just 60,000 or so because of disease, forced removal from native lands, and massacres.

A key civil rights problem was the concept of Terra nullius, which meant the Aboriginal people had no legal rights and essentially were treated as animals.

“It meant that the people didn’t exist. That practice had extraordinary consequences,” Mr. Kennedy said. “Not only did the Aboriginal people in Australia not get the right to vote until 1967, they weren’t even counted in the census until then because they were included under the Wildlife Act, the flora and fauna act, so they weren’t actually people.”

While the Aboriginal people have made a significant recovery, Crossing Cultures directly addresses their current status with a second room filled with contemporary photos that are both beautiful and challenging.

“This is a very loaded, powerful room,” he said. “It’s actually very deliberate to start here and say, ‘This is contemporary Australia. These are the issues and we’re not going to shy from them.’ It’s a very beautiful show, but there are a lot issues here that have to be addressed.”

Alien and similar

The rest of the exhibit curated by Stephen Gilchrist of the Hood Museum is organized roughly by geography as it takes visitors to the various regions of Australia and introduces them to wonderful spiritual concepts such as “the dreaming” and the “everywhen.”

The art is filled with undulations, shimmering effects, vibrant earth-tone colors, and a sense of movement. Mr. Kennedy noted that it “sings” and he improvised a little dance to express its vitality.

He noted that ancestral stories are encoded in many of the works, which capture the way the earth looks to the people who have lived there for millennia. “After a rain what happens to the desert is just amazing. It’s mind-bogglingly beautiful,” he said.

Mr. Owen, who along with Mr. Wagner will be in Toledo for the opening, said the exhibit contains an element of anthropology because it covers so much cultural ground. He remembered when he first started reading about Aboriginal art. “I started thinking, ‘Wow, these people see the world totally different than I do. Everything about them is different and alien and kind of interesting,” he said.

But then he read more and realized something contradictory: “Wow, these people are just like us,” he said, laughing. “It was about relationships, it was about status, it was about your place in the world, how you got along with other people or not. But the expression of it was so radically different than our culture that I was just fascinated.”

Opportunities

Mr. Kennedy noted there are many complicating factors with collecting Aboriginal art, from usual concerns about forgeries and ensuring artists are paid fairly, to issues such as how you communicate with people who live in remote areas and don’t speak English. He said the Toledo museum can advise anyone interested in exploring how to collect it.

He also is bullish on the idea of bringing more culturally enriching exhibits to the museum. “Just because we’re in Toledo doesn’t mean we can’t speak to the world. How do we do that? Well, we bring the world to Toledo and like with this exhibition, people will ask me, ‘Will there be a Native American exhibition?’ and I say, ‘Quite likely in the next 10 years there will be,’ ” he said.

“But I would go even further and say, ‘Why when we represent world culture, why do we not have a single, great work of Native American art?’ Because of the way we marginalize and this is a very western-centric museum.”

His solution? A Japanese exhibit is planned later this year; a big Islamic exhibit is coming next year, and the museum just featured a display of Jewish Haggadot.

Crossing Cultures: The Owens and Wagner Collection of Contemporary Aboriginal Australian Art from the Hood Museum of Art goes on display to the public for free at 10 a.m. Friday and runs until July 14.

A preview event is later today from 6:30 to 9:30 p.m. for museum members and will feature light hors d’oeuvres, contemporary Aboriginal music, and a cash bar. The cost to attend the preview for nonmuseum members is $20 at the door.

Contact Rod Lockwood at: rlockwood@theblade.com, or 419-724-6159.