O'Neill: A true believer

7/29/2001

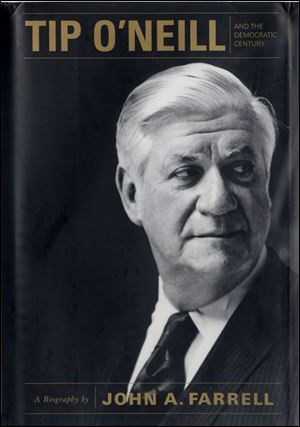

FEA Book jacket for "Tip O'Neill," by author John A. Farrell. Cover Photo: Rymm Massand

TIP O'NEILL AND THE DEMOCRATIC CENTURY. By John Aloysius Farrell. Little Brown and Co. 692 pages. $29.95.

Tip O'Neill was, for many people, the perfect caricature of a larger-than-life hack congressman - something Ronald Reagan was shrewd enough to use to great advantage. O'Neill had a huge red nose, a shambling bear-like body, a thick Boston-Irish accent, and seemed stuck forever in the New Deal era of big-city machine politics.

Few remember now, but one of Reagan's most effective TV ads in 1980 was one in which a caricature of O'Neill was driving a car with a desperate passenger (America) trying to get the oblivious congressman to notice they were almost out of gas.

Yet he was a major power and a presence in the decade he ruled the House (1977-1987) and for most of the Reagan years, he was what amounted to, for most intents and purpose, the national leader of the Democratic Party.

John Aloysius Farrell, the Washington editor of the Boston Globe, has now written a massive, honest, but sympathetic biography of his fellow Irishman, from his birth in 1912 - a few months after the Titanic went down - to his death in 1994, mercifully months before his beloved Democrats lost his equally beloved House to Newt Gingrich.

Most of the action, however, is set in the years he was speaker, years in which, as the author notes, the party of Franklin Roosevelt was falling apart. O'Neill reigned at a time when increasingly, “There were no longer enough militant union bosses, poor folk, and minorities, urban ethnic and `yellow dog' southern Democrats to negate the growing influence of suburbanites, independents, white-collar workers [and] middle-class Catholics who were now prosperous and secure enough” to vote Republican.

Tip O'Neill, this book argues, kept the faith, and in his final years in power helped preserve the inheritance of the Democratic party, keeping the faith by, as the dust jacket puts it, “representing a set of political values - justice, generosity, loyalty - that were as important as the entrepreneurial, conservative ideals of Reagan.”

Well, maybe. Tip was a decent, sentimental man who once pushed through a bill making a British boy killed in action a posthumous American citizen in half a day. “If we can't do this for this kid, why have a Congress?” he asked. He was also a shrewder legislator than he seemed, and in his last two years in power, led his troops to several signal victories, notably on Social Security, taxes, and against funding for the contras.

Yet it is hard to come away from this book without concluding that O'Neill, who did have all the virtues of the New Deal generation, had all the faults too - and his inability to change helped weaken the Democratic Party in the Age of Reagan.

“You're not my cup of tea,” he told Gary Hart when he came to see him, months before the scandals, to ask for his support. “You're this new type of liberal. I'm the old - work and wages, take care of the poor and hungry.”

Hart, as the world knows, soon self-destructed. But Democrats running on platforms more to O'Neill's liking lost 133 out of 150 states in the three presidential elections of the 1980s.

He never quite got it. “I was a New Dealer then and I'm a New Dealer now,” he said at Hyde Park in 1987. But the world had changed. The man best known for having said “all politics is local,” had survived to an age when everything was international.

When he left office, he, ironically, like his nemesis Ronald Reagan, and like other old pols dating back to Finley Peter Dunne's Mr. Dooley, had “seen his opportunities and took 'em.” Sadly, far too many today remember the Speaker mostly for the tacky TV commercials he did at the end of his life, shamelessly huckstering for Miller Lite and the Trump Shuttle, and rising magically out of a suitcase for Quality Inn. And there was the million-dollar-advance for his ghostwritten, “based on fact” memoirs.

By the time he died, he had, like so much in the America of his era, become his own best parody. Yet this biography also helps explain him, a man who grew up in an era where “the average citizen had an eighth-grade education, worked a full day on Saturday, and still did not earn the $2,000 a year needed to provide for a family.”

He came from a world when, as the author notes, “there was no such thing as health insurance. Your chance of dying in an accident, on the farm or on the job, was more than twice what it is today . . . and concepts like weekends and retirement were unheard of.” The Democratic party of his youth did a lot to change that.

Tip O'Neill knew that in what all agreed was his very big heart. Which may do a lot to explain why, in the end, he was so unwilling to change.

Jack Lessenberry is The Blade's ombudsman.