What makes an artist? Joan Acocella knows

3/24/2007

Joan Acocella writes about dance and books for the New Yorker.

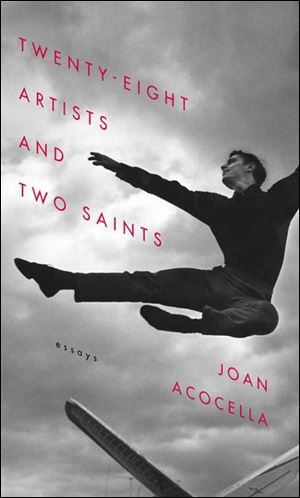

JOYCE RAVID / VIA BLOOMBERG NEWS

The book jacket for "Twenty-Eight Artists and Two Saints" by Joan Acocella is pictured in this undated handout image. Source: Random House via Bloomberg News.

You got it wrong.

A good critic suggests this.

Not just this, of course.

But a good critic casts doubt:

You ve made an assumption.

You re certain how you feel.

Now you re not so sure.

Take Joan Acocella.

By chance I finished her new book of essays and profiles, Twenty-Eight Artists and Two Saints (Pantheon, 525 pages, $30), with the one story which stands outside the book s title. The 31st piece, so to speak. It s a brief history of writer s block. I read the book out of order. Many of the stories are culled from her 15 years on the staff of the New Yorker, where Acocella writes about dance and literature; she has a loose structure in mind, an ebb and flow of theme and subject.

But her prose is so accessible and devoid of pretension, so deceptively simple, read out of order and not a thing gets lost. The middle is something of an informal history of 20th century dance; the rest are longish, biographical sketches of writers, sculptors, a pair of saints not quite thumbnail portraits, not quite the entire life story, either.

More of a thumb and a digit.

We should all have so elegant a portraitist in our corner, explaining our lives. What binds her stories is not necessarily the subject art and the people who make it but a tireless sympathy for artists and their foibles, and a challenge to the way we think of people who make art. Acocella writes in her introduction: We should love these people not just for artistic reasons, but for moral reasons.

That s kind of shocking.

What her great artists share is not, as it s romantically assumed about artists, a muse, a mental illness, a tormented soul, or a neurosis though it happens, and here it happens endlessly. For instance, patterns emerge. Food writer M.F.K. Fisher s husband killed himself when she was 33; when her mother died, she moved home at 41 to help her father and published nothing for 12 years, sitting in obscurity longer. When the father of sculptor Louise Bourgeois died, she didn t show a single piece for 11 years. There s alcoholism: Dorothy Parker, Frank O Hara, the choreographer Twyla Tharp.

That s a particularly long list.

In The Soloist, her classic portrait of Mikhail Baryshnikov, greatness is arrived at after a hellish childhood and the loss of a parent, but Acocella is quick to avoid the cause and effect of armchair psychology: The loss of a mother may explain his devotion to ballet at an early age, she writes, but to explain his talents, all of which are as much a part of him today as they were when he was twelve we must look to him alone. What magic trick, after all, explains the life of George Balanchine, who loses his family at age 9, survived the Russian Revolution, starvation, escaped only to develop tuberculosis, found success, then lost it a lifetime of loss and 425 ballets?

Joan Acocella writes about dance and books for the New Yorker.

Dignity, she allows.

The dignity of genuine guts humble, unfashionable virtues, refreshingly free of artistic romance. She argues that great art springs from artists who keep on keeping on, who show supreme patience, who recognize luck, work through the droughts, and persevere despite the odds stacked against them. Discipline, talent, and sacrifice are what draw together her subjects, not neurosis, but its opposite ... Sunday-school virtues such as tenacity and above all the ability to survive disappointment.

In which case, after so many sob stories, it takes a critic of Herculean empathy to write with depth on a topic as minor as writer s block. Acocella regards it as something like lactose intolerance a concept that other cultures, other times, have done fine without but she doesn t dismiss the real panic it instills. She mentions, for instance, that artists rarely discuss their work in psychoanalysis but focus instead on that which keeps them from returning to their work, like kids and a pile of bad reviews. When their personal, peripheral problems are solved, they quit:

They didn t know and didn t care what underlay their creative function. They just wanted to get back to it as long as it lasted.

That s one definition of art.

She writes almost exclusively about artists who show an urgency so long and through so many downturns, it s hard to say where their urgency ended and resilience began. She s not blind to missteps. Her piece on Dorothy Parker is sad, full of disappointment for a talented writer content to write fluff. Acocella falls on the side of the enthusiast critic as opposed to the scowl. But when a subject lives down to their potential, she is uncompromising. Her portrait of H.L. Mencken takes pains to explain how he gave American journalism its native language and its casualness, the way Mark Twain developed an American idiom for the novel. In the next paragraph she points out he was a philistine, with one emotion:

The pleasure of despising.

No such gene exists in Acocella. She takes on only those artists whom she admires, those worth the effort artists, more or less, like Acocella. She draws on the world. She sees connections, which gather force like a snowball on a steep glade. She makes the most esoteric art accessible. (Her dance stories, for instance, never waste an adjective on an indescribable move.)

Collectively, like the best criticism, the pieces in Twenty-Eight Artists and Two Saints say so much about Acocella, they are really not many thumbnail portraits but a single portrait.

Her own.

Contact Christopher Borrelli at: cborrelli@theblade.comor 419-724-6117.