GETTYSBURG'S 150th

‘The turning point’ in the Civil War or something less?

Some historians say significanceof bloody, 3-day fight is overstated

6/30/2013

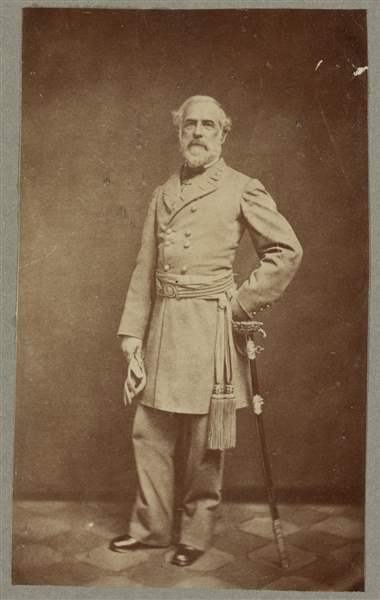

Gen. Robert E. Lee led Confederate troops at Gettysburg.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

Gen. Robert E. Lee led Confederate troops at Gettysburg.

GETTYSBURG, Pa. — Ten major roads came together at Gettysburg in 1863. That convergence allowed Union and Confederate forces to assemble there quickly for a three-day fight that remains the biggest and bloodiest battle in the history of the Americas.

Gen. George G. Meade took over Union forces days before the battle.

By the evening of July 3, about one in four of the 94,000 Northern soldiers was killed, wounded, captured, or missing. The proportion of casualties in the Southern ranks of about 72,000 was one in three.

RELATED CONTENT: Read more about 150th Anniversary of The Battle at Gettysburg

PHOTO GALLERY: Click here to view

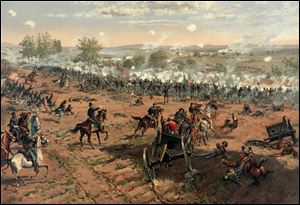

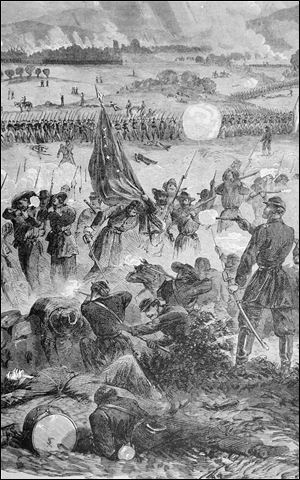

A painting by Thure de Thulstrup titled ‘Hancock at Gettysburg’ shows Gen.Winfield Scott Hancock leading his troops on Cemetery Ridge during Pickett’s Charge.

Leading the armies were Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee and Union Gen. George G. Meade. General Lee had arrived at Gettysburg after winning dazzling victories against a series of Union generals. Many of General Lee’s battlefield foes had been his comrades during his 32-year U.S. Army career. General Meade had been put in command of Union forces just three days before the battle.

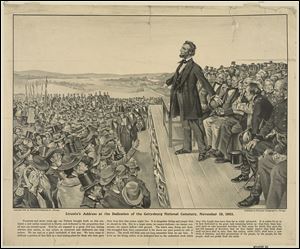

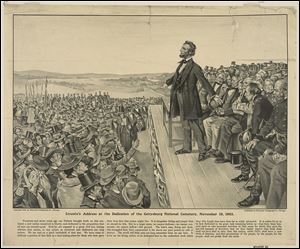

A lithograph shows President Abraham Lincoln speaking at the dedication of the national cemetery at Gettysburg in November, 1863. During that speech, known as the Gettysburg Address, he dedicated the nation to a ‘new birth of freedom.’

Almost from the moment the fighting there ended, on-the-scene reporters and editorial writers began describing the battle in monumental terms. Some compared it to Napoleon’s 1815 defeat at Waterloo. That view was bolstered by the near simultaneous surrender of the Confederate stronghold at Vicksburg, Miss., on July 4. Those victorious Union troops were led by Gen. Ulysses S. Grant.

Library of Congress Confederate dead at Rose Woods in Gettysburg, PA Photograph attributed to Alexander Gardner July 5, 1863. BLADE

Many modern historians, however, think the battle’s significance has been overstated. “Terms like ‘the turning point’ and ‘high-water mark of the Confederacy’ are not the products of military analysis, but the words of journalists,” Carol Reardon said in a recent interview.

Larry Roberts/Post-Gazette February 5, 2013 local civil war barcousky Gettysburg, Pickett's Charge image from Volume 2 of Harper's Pictorial History of the civil War, published in 1868 Courtesy of Senator John Heinz History Center Original Filename: Tiffcivilwarbarcousky44.tif BLADE

Ms. Reardon, George Winfree Professor of American History at Penn State University, and Tom Vossler, a retired Army colonel and former director of the Army’s Military History Institute, are co-authors of the just-published A Field Guide to Gettysburg.

A lithograph shows President Abraham Lincoln speaking at the dedication of the national cemetery at Gettysburg in November, 1863. During that speech, known as the Gettysburg Address, he dedicated the nation to a new birth of freedom.'

The fight had not begun well for the Union on the morning of July 1. A U.S. Cavalry commander, Gen. John Buford, had sought to hold Gettysburg and its important crossroads from ridges north and west of the town. Despite the arrival of reinforcements commanded by Maj. Gen. John Reynolds, Northern troops were forced to retreat south through the town. General Reynolds was killed.

Union soldiers, however, were able to hold and began to fortify Cemetery Hill on the south end of town. “I give full credit to Buford and Reynolds in recognizing the key ground — Cemetery Hill, Cemetery Ridge, and the Round Tops,” Mr. Vossler said. Their first-day maneuvering gave Union forces control of both the high ground and several major roads.

Actions by General Buford and General Reynolds assured that their commander, General Meade, had multiple options for action, including the choice of not challenging the Confederates at Gettysburg, Ms. Reardon said.

The Union line formed at Gettysburg usually is described as a fishhook. The 1993 movie Gettysburg focuses on the heroic defense of Little Round Top by the 20th Maine and its commander, Col. Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain. Little Round Top on July 2 was the extreme left flank of the Union Army’s line — the eye of the fishhook.

While Colonel Chamberlain’s troops carried out their famous bayonet charge against Confederate Gen. John Bell Hood’s Alabamians, other Union soldiers were engaged in a similar dogged defense at the other end of the federal line.

“It doesn’t take one whit away from the 20th Maine to recall that the 137th New York was doing something very similar on Culp’s Hill,” Ms. Reardon said. Culp’s Hill was on the far right of the Northern line — the barb on the fishhook. The New Yorkers, led by Col. David Ireland, had held out against multiple Confederate attacks on July 2, ending the evening’s fighting at Culp’s Hill with their own bayonet charge.

The single event most people associate with Gettysburg took place on July 3, the final day of battle. Pickett’s Charge, a Confederate infantry attack on the left center of the Union line, was only part of General Lee’s battle plan for that day.

“Lee was going to build on the successes of July 2 and again launch early morning attacks on the two flanks,” Ms. Reardon said. As those battles drew in more and more troops, Lee concluded Meade had been able to strengthen his right flank by withdrawing troops from the center, she said. The Confederate commander believed that move would have weakened the Northern line around the famous “Copse of Trees.”

“Lee has been in command [of the Army of Northern Virginia] for 13 months ... and his boys have done everything he asked them to do,” Mr. Vossler said. Despite the skepticism of his corps commander, Gen. James Longstreet, Lee gave the order for the Confederate advance. While a frontal assault, uphill, against strong enemy positions seems almost suicidal, Ms. Reardon said it had several arguments in its favor.

Similar attacks succeeded multiple times for the Confederates, she said. They included victories at Gaines’ Mill, Va., in 1862, and at Chancellorsville, Va., and Chattanooga, Tenn., in 1863, before and after Gettysburg.

Ms. Reardon and Mr. Vossler said their many walks across the mile-wide expanse between Confederate lines at Seminary Ridge and Union defenses on Cemetery Ridge gave them new insight into the battlefield topography. While it looks like the ground between the two ridges is wide open, it is rolling as far as the Emmitsburg Road. Those undulations gave the Confederates significant cover for much of their attack, Ms. Reardon said. “The real killing zone is the last 400 yards,” she said.

While some Confederates under Gen. Lewis Armistead broke through the Union line at the “Angle,” they couldn’t hold the position.

“It is all my fault,” General Lee is quoted as saying as the remnants of General Longstreet’s forces fled back to the Confederate lines after the unsuccessful assault.

As was Gen. George McClellan after the Battle of Antietam, General Meade has been criticized for failing to pursue General Lee’s retreating army before it could escape back into Virginia. Mr. Vossler and Ms. Reardon agreed that it was unrealistic to expect the exhausted Union soldiers to mount a pursuit. “The Union was as disorganized in victory as the Confederates were in defeat,” Ms. Reardon said.

Gettysburg was important to the ultimate Northern victory in 1865, but it did not spell the end of the Confederacy, both agreed. Sixty days after the losses at Gettysburg and Vicksburg, the South won a major victory at Chickamauga, Ga., Mr. Vossler said.

“The results of Gettysburg and the capture of Vicksburg raised concern in the South, but the attitude was, ‘We’ve seen tough times before, and we will come back,’” Ms. Reardon said.

Despite the heavy losses during the battle, many in the North had a feeling of euphoria after Gettysburg. “But, of course, the war continued for another two years,” she said.

The two historians pointed to other major turning points in the war.

They included the Union win at Antietam, which encouraged President Abraham Lincoln to issue his Emancipation Proclamation, Mr. Lincoln’s speech at the national cemetery at Gettysburg that dedicated the nation to a “new birth of freedom,” and Mr. Lincoln’s 1864 re-election victory against the Democratic Party’s “Peace candidate,” General McClellan.

Gettysburg undoubtedly was a significant event in the war, they agreed. “I’ll go with ‘a’ turning point, but not ‘the’ turning point,” Ms. Reardon said.

Block News Alliance consists of The Blade and the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Len Barcousky is a staff writer for the Post-Gazette.

Contact Len Barcousky at: lbarcousky@post-gazette.com or 724-772-0184.