Traveling on Central Asia's Silk Road

On the trail of history’s trade caravans

4/30/2017

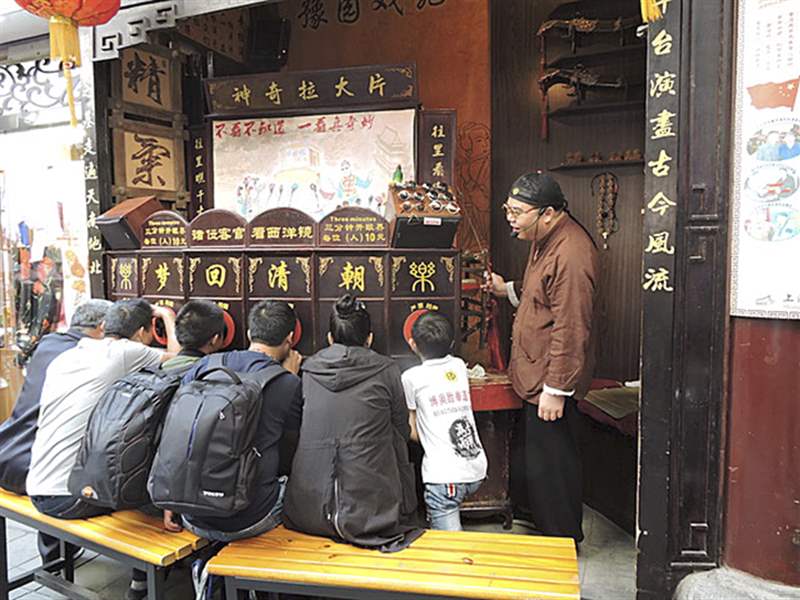

Customers peer through a bioscope in Shanghai to see a show of still pictures with commentary from the operator.

S. AMJAD HUSSAIN

First in a series

SHANGHAI — Just the mention of the Silk Road conjures up images of trade caravans making their slow and plodding way across China on their way to Central Asia and Europe.

The road was first mentioned in ancient Chinese travelogues and in the diaries of the Chinese Buddhist pilgrims who went westward from the city of Xian, the ancient capital of the Qin (pronounced Chin) dynasty. They left detailed accounts of the places they visited and the roads they traveled.

The idea to travel the Silk Road in China continuing on to its southern extension into Pakistan has always intrigued me. To travel on the northern fringes of the massive Taklamakan Desert and visit the storied cities of Xian, Urumqi, and Kashgar is something I have wanted to do for years.

The ancient stories of old caravansaries of yore drew me in. Tales of travel-weary caravaneers unrolling their bedrolls, sipping tea, and gazing at the crackling fire while sharing tales of their travel and talking about the perils that lay ahead, intrigued me.

Then I received a surprise phone call from KM Ali of Seattle. Mr. Ali is a soft-spoken aeronautical engineer who recently retired from Boeing. I know him from his adventurous forays into the deserts and northern mountains of Pakistan. He said he had put together a group of eight explorers for an expedition along the Silk Road and invited me to join them.

Others in the group include Mr. Ali’s wife, Yasmin, a veteran of many adventures.

From Karachi, Pakistan, come Sabiha Omar and her daughter, Mahera, a videographer and a writer who is a graduate of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Also on the expedition is Babar Ali, a Harvard-educated executive at Liberty Mutual in Boston, who is an experienced photographer and like his father, KM Ali, has an adventurous spirit.

The other three members to join us from Karachi are the husband and wife team of Drs. Imran and Nasim Chaudhry, and writer Lubna Khan.

The team met in Shanghai to get acquainted and to explore the city. Once a small coastal village, Shanghai has over the centuries and particularly in the past 70 years become a megacity with a population of 25 million. It is the financial nerve center of Asia and the fashion capital of China. The city is studded with high-rise buildings and old neighborhoods.

Colonial occupiers of China left their mark on the city architecture. An evening walk on the Bund, a promenade on the river in the former Foreign Quarter, is a sight to behold.

It was Shanghai where the art of silk making was developed and the silk made in Shanghai found its way to Europe via the Silk Road.

According to legend, Emperor Huang, the 2500 B.C.E. Chinese leader known as the Yellow Emperor and the Yellow God, was sipping tea under a mulberry tree when a fine filament dropped from the tree into his cup. That led to the discovery of the silkworm and the start of the silk making in China.

Silkworms are amazing creation of nature. In their 60-odd days of existence they undergo amazing changes. They grow from smaller-than-a-pinhead eggs into worms of 2 to 3 inches in length feeding continuously on mulberry leaves. Then they start secreting an extremely thin silk filament and in 4 to 6 weeks they spin a cocoon around themselves. If left alone, the pupae break through the cocoon in the shape of a winged moth. Before ending their life cycle they mate, and females lay up to 500 eggs.

In order to harvest silk, the cocoons are immersed in boiling water to kill the enclosed pupae before they come out of the cocoons and damage the continuity of the silk filament. When unraveled, each cocoon yields a single strand of silk measuring 500 to 700 yards in length.

The see-through fabric the ancient Chinese made from the silk strands was a sensation in Europe, and increasing demand for silk made the Chinese emperors rich.

The Romans believed that silk grew on trees and called it the wool of the Chinese forests. They also believed that the Chinese “comb off leaves their delicate down.” The Chinese were able to hold on to the secret of silk manufacturing for almost 1,600 years until, as one story goes, Nestorian monks smuggled the silkworm eggs out of China to Byzantine concealed in their hollowed-out staffs.

The attachment of the word silk to the network of caravan routes across China is rather recent. It first appeared in a multivolume historical geography by the noted German traveler and geographer Baron Ferdinand von Richthofen. He used the word in plural — Silk Roads — to denote a network of east-west routes that connected China across the Pamir Mountains with Central Asia and Europe.

Tourists to Shanghai, where the art of silk making was developed, can view the popular Water City nearby.

There were also the southern extensions across the Hindu Kush and the Karakorum Mountains to the present day Afghanistan, Pakistan, and northern India. On these roads Chinese silk moved during the Han Dynasty, 206-220 B.C.E., but silk was just one commodity exported and imported by China.

Many other commodities such as domesticated horses, cotton, paper, and gunpowder traveled along the Silk Road. These had more far reaching impacts on the history of Eurasia than silk alone.

But more important than the silk and other goods that crossed Asia on the Silk Road may have been the arts, literature, music, languages, and religions that moved freely in both directions. They found fertile ground in distant lands.

Buddhism, Christianity, and Islam were spread by caravans plying the vast expanses of distant lands that were connected by the Silk Roads. The caravansaries, far from being towers of Babel where no one understood one another, were connected by the Persian language that for many centuries was the lingua franca on those ancient rails.

It was also along the Silk Road that Indian Buddhist statuary art met the Greek statuary art and developed a fusion where Buddha began wearing a Greek toga instead of an India loincloth.

The Silk Road my team of adventurers will traverse will skirt the northern edge of the Taklamakan, a large formidable desert in the western China.

“As I was growing up in Pakistan,” KM Ali, our team leader told me, “I was fascinated by the stories of trade caravans coming to Peshawar through the Khyber Pass. They would bring goods and stories from far away places like Samarkand, Balkh, and Bukhara, once the fabled cities of the Silk Road.”

He said that in not too distant a past, not more than 70 years ago, the famous Street of Storytellers in Peshawar was a kaleidoscope of faces from lands near and far.

Most Silk Road caravans traveled along the northern and southern fringes of the Taklamakan Desert. The ever-changing topography the Taklamakan has, over millennia, swallowed a number of important oasis towns. It was from the writings of Chinese Buddhist monks who traveled the road in search of ancient Buddhist manuscripts and scrolls that we learned of the existence of those cities.

Customers peer through a bioscope in Shanghai to see a show of still pictures with commentary from the operator.

Using that information many European explorers took to the desert and excavated some of the buried cities and carted off countless frescoes and ancient Buddhist manuscripts to their home countries. The names of the Englishman Sir Marc Aurel Stein and the Swede Sven Hedin top the list.

The exploits of these two and many other high-brow robbers is described in Foreign Devils on the Silk Road, a fascinating 1980 book by Peter Hopkirk.

As an aside, Mr. Hedin discovered the source of the Indus River in the Kailas mountain range in western Tibet in the early 1900s. In 1996, I led a team to the source of the Indus following his footsteps.

In the past, distances on the Silk Road were measured in the time it took the caravans to reach various oases along the long and arduous journey. Today, one does not hear the tolling bells of an approaching caravan in an oasis town.

The same journey that took many months can now be done in few days in traveling on asphalt roads in buses and cars or riding China’s fast bullet trains in some parts. The oases are now flourishing cities and towns where trading still happens and wares are still sold from different parts of China and the Asian steppe.

Times have changed, but human curiosity to learn about other people and their cultures remains embedded in the human heart. The present Silk Road expedition is an attempt to look at the past through the clear lens of today.

That is what drew Mahera Omar, the filmmaker and writer, to our expedition.

“I enjoy meeting people and documenting glimpses of their lives,” she said. “What better place to meet people than the ancient caravan routes?”

In the next few weeks our expedition of explorers will travel along the Taklamakan Desert to the cities of Xian, Dunhuang, Iiauguan, Turpan, Aksu, and Kashgar. At Kashgar, I will part company with the team, and as I fly home, they will continue across the Karakorum Mountains into Pakistan all the way down to the Arabian Sea.

Next: From Shanghai, our next oasis will be the ancient Chinese capital of Xian (pronounces SheeAaN), where the ancient terracotta army awaits our arrival.

S. Amjad Hussain, a columnist for The Blade, is an emeritus professor of surgery and humanities at the University of Toledo. He is a native of Peshawar, Pakistan. Contact him at aghaji@bex.net.