Civil rights pioneer Rosa Parks dies at 92; local highway was named in honor

10/25/2005

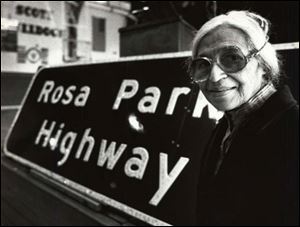

Rosa Parks stands next to a sign at Scott High School in Toledo in 1990. Part of I-475 is designated as Rosa Parks Highway.

DETROIT Rosa Parks, a black seamstress whose refusal to relinquish her seat to a white man on a city bus in Montgomery, Ala., almost 50 years ago helped touch off the civil rights movement, died yesterday. She was 92.

Her death was confirmed late last night by Dennis Archer, the former mayor of Detroit. He served as Mrs. Parks guardian.

For her act of defiance in 1955, Mrs. Parks was arrested, convicted of violating the segregation laws, and fined $10, plus a $4 court fee.

In response, blacks in Montgomery boycotted the buses for nearly 13 months while mounting a successful Supreme Court challenge to the Jim Crow law that enforced their second-class status on the public bus system.

The events that began on that bus in the winter of 1955 captivated the nation and transformed a 26-year-old preacher named Martin Luther King, Jr., into a major civil rights leader.

It was Mr. King, the new pastor of the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery, who was drafted to head the Montgomery Improvement Association, the organization formed to direct the nascent civil rights struggle.

Mrs. Parks arrest was the precipitating factor rather than the cause of the protest, Mr. King wrote in his 1958 book, Stride Toward Freedom. The cause lay deep in the record of similar injustices.

Her act of civil disobedience, which seems a simple gesture of defiance so many years later, was in fact a dangerous, even reckless move in 1950s Alabama.

By refusing to move, she risked legal sanction and perhaps even physical harm.

But she set into motion something far beyond the control of city authorities. Mrs. Parks clarified for public consumption far beyond Montgomery the cruelty and humiliation inherent in the laws and customs of segregation.

That moment on the Cleveland Avenue bus turned a very private woman into a reluctant symbol and torchbearer in the quest for racial equality and of a movement that became increasingly organized and sophisticated in making demands and getting results.

Even in the last years of her life, the increasingly frail Mrs. Parks made appearances at events and commemorations, saying little but lending the considerable strength of her presence.

In 1990, Mrs. Parks visited Toledo for a dedication ceremony at Scott High School. She was 77 at the time.

One year earlier, Ohio Gov. Dick Celeste had signed a bill naming a section of I-475 that runs through Lucas and Wood counties the Rosa Parks Highway.

The measure was introduced by the late Rep. Casey Jones, a Toledo Democrat.

Mr. Jones said he decided against the names of Toledo-area civil rights activists for the honor because many of the motorists who used the highway would not recognize a local name.

By allowing interstate number 475 to be named after her, Ohio would be following suit of other states such as Michigan, who have named roads and streets after her, he said.

The stretch is designated as I-475 on highway maps, but commemorative markers have been installed at Auburn Avenue and Jackman Street westbound entrances to the highway and at the eastbound entrance near State Rt. 25 at Perrysburg.

Over the years myth tended to obscure the truth about Mrs. Parks.

Speaking in 1992, she said history too often maintains that my feet were hurting and I didn t know why I refused to stand up when they told me.

But the real reason of my not standing up was I felt that I had a right to be treated as any other passenger, she said. We had endured that kind of treatment for too long.

Her arrest triggered a 381-day boycott of the bus system organized by Mr. King, who later received the Nobel Peace Prize for his work.

At the time I was arrested I had no idea it would turn into this, Mrs. Parks said 30 years later. It was just a day like any other day. The only thing that made it significant was that the masses of the people joined in.

The Montgomery bus boycott, which occurred one year after the U.S. Supreme Court s landmark declaration that separate schools for blacks and whites were inherently unequal, marked the start of the modern civil rights movement.

The movement culminated in the 1964 federal Civil Rights Act, which banned racial discrimination in public accommodations.

After taking her public stand for civil rights, Mrs. Parks had trouble finding work in Alabama.

Amid threats and harassment, she and her husband Raymond moved to Detroit in 1957. She worked as an aide in Rep. John Conyers Detroit office from 1965 until retiring Sept. 30, 1988.

Raymond Parks died in 1977.

Rosa Louise McCauley was born in Tuskegee, Ala., on Feb. 4, 1913, the elder of Leona and James McCauley s two children. Although the McCauleys were farmers, Mr. McCauley also worked as a carpenter and Mrs. McCauley as a teacher.

Rosa attended rural schools until she was 11 years old, then Miss White s School for Girls in Montgomery. She attended high school at the Alabama State Teachers College, but dropped out to care for her ailing grandmother.

It was not until she was 21, and had been married for two years, that she earned a high school diploma. She was 42 when she committed the act of defiance that was to change the course of American history and earn her the title mother of the civil rights movement.

Shy and soft-spoken, she often appeared uncomfortable with the near-beatification bestowed upon her by blacks, who revered her as a symbol of their quest for dignity and equality.

Looking back in 1988, Mrs. Parks said she worried that black young people took legal equality for granted. Older blacks, she said have tried to shield young people from what we have suffered. And in so doing, we seem to have a more complacent attitude.

We must double and redouble our efforts to try to say to our youth, to try to give them an inspiration, an incentive, and the will to study our heritage and to know what it means to be black in America today.