INFRINGEMENT SUITS

‘Patent trolls’ strike fear in businesses large, small

7/20/2013

Erich Spangenberg's firm, IPNav, has sued 1,638 companies in the last five years, more than any other patent-assertion entity, records show.

NEW YORK TIMES

If you’re a corporate executive, this might be one of the last sentences you want to hear: “Erich Spangenberg is on the line.” Invariably, Mr. Spangenberg, the 53-year-old owner of IP Navigation Group, known as IPNav, is calling to discuss a patent held by one of his clients, which he says your company is infringing — and what are you going to do about it?

Mr. Spangenberg is likely to open the conversation on a diplomatic note, but if you put up enough resistance or try to shrug him off, he can also, as he put it, “go thug.”

He demonstrated this recently in his rented apartment in Paris. His voice dropped, the curse words flowed, and he spoke with carefully modulated menace.

Mr. Spangenberg’s company, based in Dallas, helps “turn idle patents into cash cows,” as it says on its Web site. A typical client is an inventor or corporation, with a batch of patents, demanding a license fee from what it contends is an infringer, usually a titan in the tech realm. His weapon of choice — the brass knuckles of his trade, so to speak — is the lawsuit.

In the last five years, IPNav has sued 1,638 companies, according to a recent report by RPX, a patent-risk management provider, more than any other entity in the patent field.

“To get companies to pay attention, in some percent of the market, you need to whack them over the head,” Mr. Spangenberg said. “In our system, you can’t duel, you can’t offer to fight in the street, which would be fine with me.”

This combat readiness has made Mr. Spangenberg, a high-school dropout raised in Buffalo, very rich. He gets about $25 million a year, he said, which is at least a couple of million more than the nation’s top bank executives. His 14,000-square-foot home in Dallas is now on the market for $19.5 million. He often flies on a company jet, and at one point he owned 16 cars, six of them Lamborghinis.

His clients, who pay IPNav a percentage of any recovery, contend that he earns every dollar.

“Erich saved our bacon,” said Steve Dodd, a patent holder with a client company called Parallel Iron. “We were more than $1 million in debt and I was getting ready to file for bankruptcy.”

Mr. Spangenberg’s opponents use less flattering terms to describe his work. Like shakedown artist. Or patent troll.

The term broadly refers to people who sue companies for infringement, often using patents of dubious value or questionable relevance, and then hold on like a terrier until they get license fees. In recent years, patent trolls — they prefer “patent-assertion entities,” — have gone from low-profile corporate migraine to mainstream scourge.

This is partly because the number of patent-infringement suits has more than doubled in recent years, to 4,731 cases in 2012 from 2,304 in 2009, according to that RPX report. The cost to businesses, which pass along the expense to consumers, is immense. One study found that U.S. companies — most of them small or medium-sized — spent $29 billion in 2011 on patent-assertion cases.

“And only about $6 billion of that money wound up in the hands of inventors,” said James Bessen, a study co-author a professor at the Boston University school of law.

“As for the other $23 billion, most of it goes to legal expenses, both for defendants and patent troll companies, with the rest going to operating expenses of the trolls — overhead and marketing — and finally, patent troll company profits,” Mr. Bessen. “That’s why we call this type of litigation a tax on innovation. It discourages innovation much more than it encourages it.”

The notoriety of trolls also arises from legal claims that, at minimum, sound absurd.

Like the patent-assertion entity that last year mailed letters to companies contending it had a patent on emailing scanned documents and asking for a license fee of $1,000 per employee. Or the company that has sued for license fees from podcasters through a patent originally filed in 1996, long before podcasts were conceived.

The inevitable counterattack on patent asserters has begun. In June, President Obama announced a handful of executive orders “to protect innovators from frivolous litigation.”

Companies, large and small, are fighting back, and figures as varied as Judge Richard Posner of the 7th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals and Marc Maron, a stand-up comedian and podcast host, have denounced trolling.

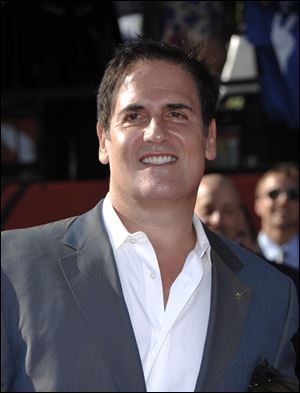

Mark Cuban, owners of the NBA’s Dallas Mavericks, recently gave the Electronic Frontier Foundation $250,000 to help finance “The Mark Cuban Chair to Eliminate Stupid Patents.”

Mark Cuban, owners of the NBA’s Dallas Mavericks, recently gave the Electronic Frontier Foundation $250,000 to help finance “The Mark Cuban Chair to Eliminate Stupid Patents.”

Mr. Spangenberg has been called “a costly nuisance,” “one of the most notorious patent trolls in America,” and many unprintable names in the comments sections of Web sites such as Techdirt.

Because of his 5 feet, 6 inch-stature, Mr. Spangenberg said he was bullied as a child but always fought back, he said. He usually lost.

This has given him a lifelong hatred of bullies, which explains, he said, why he wound up in a job where he often stands with a small company assailing a larger one.

But IPNav doesn’t exactly fight using the Marquess of Queensberry rules.

In a 2008 ruling, U.S. District Judge Barbara Crabb in Wisconsin concluded that Mr. Spangenberg was involved in witness tampering — specifically, inducing a lawyer to “intimidate a witness on the eve of trial.”

The 62-page ruling was in a case brought by DaimlerChrysler against a company owned by Mr. Spangenberg called Taurus IP LLC. The carmaker accused Mr. Spangenberg of breaking a 2006 we-won’t-sue-you-again agreement over certain tech patents.

“It was a mauling,” Mr. Spangenberg said of the ruling, now under appeal.

However, soon after Judge Crabb’s decision, IPNav’s phone was ringing with new business. RadioShack Corp., Bridgestone Corp., and others wanted to strike various deals to monetize their patents.

In the patent world, Mr. Spangenberg said, he has cultivated a reputation as a bit of carnivorous monster, but some opponents say he can be perfectly reasonable.

One, a lawyer named David Tsai, said IPNav’s lawyers dropped a case against his clients — Hulu, Amazon, and Twitter — after he showed that they were not infringing.

But such comity might be the exception.