Blind jobseekers deal with wary employers

Despite technology, hurdles are high

11/9/2013

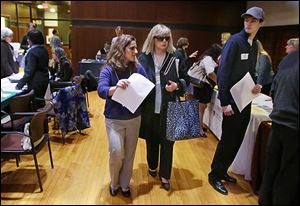

Maura Mazzocca attends a job fair for the visually impaired with the aid of volunteer guide Kate Loosian, left, at Radcliffe Yard in Cambridge, Mass.

CAMBRIDGE, Mass. — Back in the late 1980s, when Maura Mazzocca was a human resources administrator with a Boston-area firm, a blind man showed up to apply for a job. She remembers the encounter ruefully.

“What I kept thinking about was, ‘How can this man work in a manufacturing company?’” she recalled, saying she looked past his abilities and saw only his disability.

“I wish now I’d given him a chance.”

That reflectiveness is heartfelt. Ms. Mazzocca lost her own eyesight in 1994 through complications related to diabetes. Now a jobseeker herself, she knows firsthand the many hurdles the blind must overcome in pursuit of full-time work.

At a job fair last month for blind and low-vision people, she went from table to table, with a sighted volunteer by her side. Some of the other 80 jobseekers carried white canes, a few had guide dogs.

Like the rest, Ms. Mazzocca was greeted with firm handshakes and encouraging words — but none of the employers she spoke with had job openings matching her interests and qualifications.

The venue was the former Radcliffe College gymnasium where Helen Keller exercised en route to becoming the first deaf/blind person to earn a bachelor of arts degree in 1904. Over the ensuing decades, Ms. Keller helped raise public awareness of blindness and empathy for those affected by it.

Yet blind people remain largely unwanted in the U.S. workplace, despite technological advances that dramatically boost their capabilities. Only about 24 percent of working-age Americans with visual disabilities had full-time jobs as of 2011, according to Cornell University’s Employment and Disability Institute.

“There’s a lot of stigma, a lot of obstacles,” said Ms. Mazzocca, 51. “It comes down to educating employers. ... It’s going to take a really long time, if ever, for them to see us for who we are and what we bring to the table.”

What they bring, according to national advocates for the blind, is a strong work ethic and deeper-than-average loyalty to their employers. That’s in addition to whatever talents and training they bring, just like any other applicant.

While good jobs are hard to come by for anyone, the blind face added challenges. Even employers professing interest in hiring blind people often don’t follow through out of concern that they might be a bit slower with key tasks or require assistance that could be burdensome.

In some cases, said Ms. Mazzocca, who has held professional jobs since she lost her sight, “They’re thinking, ‘What if I have to fire them? Will they sue me?’”

Many national and local organizations are working hard to change the equation, through a mix of outreach to employers, training and counseling for jobseekers, and support for technological development. Though sometimes costly, myriad devices and technologies can convert computer text or printed pages into Braille or spoken words.

Still, the steadiest sources of jobs for many blind people are nonprofit organizations with missions related to blindness and other disabilities.

Among them is National Industries for the Blind, a network of 91 nonprofit agencies that collectively employ about 6,000 blind people. It recently conducted a survey of 400 hiring managers and human resource executives nationwide.

The survey found 54 percent of hiring managers said there were few jobs at their company that blind employees could perform, 45 percent said accommodating such workers would require “considerable expense,” 42 percent said blind employees would need someone to help them on the job, and 34 percent said they were more likely to have work-related accidents than sighted employees.

“We’re having to deal with lots of misconceptions and myths,” said Kevin Lynch, CEO of National Industries for the Blind. “From that standpoint, the study was clearly disappointing, but it gives us the opportunity to find a way forward.”

Mr. Lynch and his colleagues take heart from federal initiatives that have expanded hiring of blind people by government agencies and federal contractors. They also are encouraged by efforts of the U.S. Business Leadership Network, a coalition led by several dozen major corporations seeking to boost employment of people with disabilities, including blindness.

Another initiative called CareerConnect, launched by the American Foundation for the Blind, offers an array of resources and advice for blind jobseekers, including a mentorship program to connect them with blind people working in the professions they aspire to.

“We are one of the best kept secrets here in this country,” said Mr. Lynch. “We need to change that.”

He is among a number of blind Americans who have built successful careers as advocates for the visually impaired, but the pathway often is difficult.

Frederic Schroeder, who served as commissioner of the Rehabilitation Services Administration under President Bill Clinton, recalls sending out 35 job applications after earning his master’s degree in special education — and getting not a single offer in reply.

Such rejection can be demoralizing, said Mr. Schroeder, now a professor of vocational rehabilitation with San Diego State University and a vice president of the National Federation of the Blind.

“We need to make sure blind people don’t think, ‘Society doesn’t want me,’ and stop trying,” he said. “If a person gives up hope of finding a suitable job, it’s a terrible waste of human resources. It’s terrible for people to live in poverty simply because of public misunderstanding.”

About 31 percent of working-age people with visual impairments live below the poverty line, roughly double the overall national rate, according to Cornell’s Employment and Disability Institute.

This was the third year for the event. Marianne Gilmore of the Carroll Center for the Blind in Newton, Mass., one of the sponsors, said about 190 jobseekers attended during the first two years, collectively garnering two internships and perhaps a half-dozen full-time jobs.

Even with no job offers, Ms. Mazzocca was glad she attended. “People are not coming here expecting to get a job,” she said. “If they did, they’d be disappointed.”

She graduated from Westfield State College in 1984. A series of jobs followed, including a stint as human resources administrator with EG&G Torque Systems in Watertown, Mass., where she encountered the blind jobseeker.

In 1994 she lost her sight. She learned skills through the Carroll Center and landed a job with Fidelity Investments in 1999. She gave that up in 2001, returning to work in 2010 at Hanscomb Air Force Base, near Burlington. She lost the job after 16 months.

“I did have room for improvement — I don’t think the fact that I was blind had anything to do with it,” Ms. Mazzocca said.

She now hopes to find work as a diversity coordinator, either for a municipality or a business.

Among the 29 employers at the job fair were TD Bank, retailer T.J. Maxx, and several branches of Harvard University, including the job fair’s host — the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study.