EDITORIAL

Treasure hunt

7/2/2012

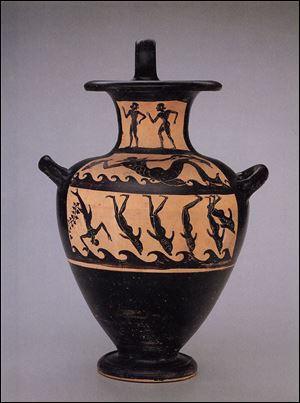

The water vessel has been on display in Toledo since 1982.

This summer, the Toledo Museum of Art will send one of its most prized possessions to Italy. This painful but necessary parting highlights how the sometimes shady business of museum acquisitions has changed.

Click here to view more Blade editorials.

The piece is a 20-inch-tall water jug, called a "kalpis," produced in southern Italy or Sicily in the 6th century B.C. Acting on the advice of a longtime curator, the museum bought the kalpis in 1982 from a Swiss dealer for $90,000.

At the time, it was considered a feather in the museum's cap. New York's prestigious Metropolitan Museum of Art also coveted the ancient vessel. But it turns out the jug was looted.

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, European and American museums, universities, and private collectors routinely pillaged ancient ruins from Peru to Italy to China, often with the cooperation of the foreign governments.

By the mid-20th century, countries began to object to the looting of their national treasures. Italy's Fascist government passed a law in 1939 that made all future archaeological finds the property of that country.

But a black market in ancient artifacts continued to flourish. Nefarious dealers employed entrepreneurs who dug up precious objects in the dead of night. The objects would be cleaned, restored, and smuggled out of the country.

Documents were forged to "prove" the objects had been privately owned for years or generations. Dealers, collectors, and museums often were not inclined to look too closely at the paperwork.

The papers that accompanied the Toledo museum's water jug claimed it had been the property of a Swiss hotel owner since 1935. But in 1995, a raid on a Swiss warehouse owned by an Italian antiquities dealer turned up thousands of Polaroid photos of ancient objects -- including the kalpis -- that appeared to have been recently dug up. Polaroid photos did not exist before the 1940s.

The path from that discovery to the museum's decision to return the kalpis to Italy has been long. To the museum's credit, it held out against U.S. Immigrations and Customs Enforcement threats to seize the vessel until it was satisfied that it had indeed been looted.

The museum's doubts have been addressed, so it is arranging to return the object to Italy by the end of the summer. As director Brian Kennedy properly noted, it's "the right thing to do."

Last year, the museum returned an 18th-century candy dish looted from a German museum during World War II. Mr. Kennedy said it doesn't appear any other pieces of questionable provenance are in the museum's collection.

Toledo may never know how much previous museum officials here knew or suspected about the 2,500-year-old water container they snatched from under the nose of the Met three decades ago. It is enough to know that museum officials today have acted honorably.

It cost $90,000 to have a beautiful example of ancient pottery serve as a centerpiece of the museum's collection for 30 years. That's a pretty good deal.