Speaking from the grave

2/8/2013

Richard III

ACCORDING to an old proverb, a kingdom can be lost because of a single missing horseshoe nail. The proverb often is associated with England’s last Plantagenet king, Richard III, who lost not only his kingdom but also his life in 1485.

Richard is remembered largely as the villain of Shakespeare’s eponymous play. The character is hunchbacked, with a withered arm; his outward deformities manifest his inner evil.

He was accused in the deaths of his two nephews, one of them the rightful heir to the English throne. The usurper lost his crown to Henry Tudor two years later, ending the War of the Roses.

Richard’s final resting place also was lost some 50 years after his death, when Henry VIII sold off England’s monastic estates and the church where Richard was buried was dismantled. Thanks to intrepid detective work, his shallow grave was rediscovered last year beneath a concrete parking lot.

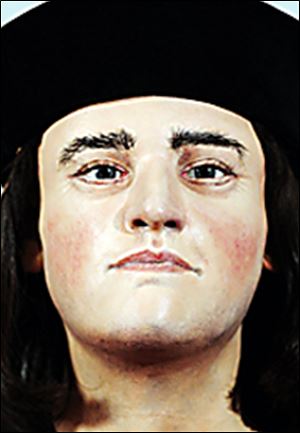

This week, the skeleton and computer-reconstructed face of the much-maligned monarch were put on display, as were details about his final moments. They demonstrated that outside of the theater, interior evil does not show through.

Richard’s body was distorted by scoliosis, but he was no Quasimodo. His arms were of normal size, and his computer-generated visage looked more like the liberal reformer he was than the murderer he was claimed to be.

Still, the last English king killed in battle stirred passionate enmities. After Richard was killed, he evidently was stripped, thrown across a horse, and stabbed and cut numerous times by his enemies before he was dumped in a grave two feet deep and barely big enough to accommodate his slight frame.

Richard’s hands were tied, even in death, and his feet were missing. Perhaps his enemies hoped to prevent his ghost from haunting their nightmares, as the ghosts of Richard’s victims haunted his dreams in the Bard’s account.

But the unkindest cut of all was a stab wound in Richard’s buttocks. It was inflicted after the monarch was dead, along with other “humiliation wounds,” similar to the indignities imposed on longtime dictator Moammar Gadhafi at the hands of Libyan rebels in 2011.

In Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar, Mark Antony says that “the evil that men do lives after them; the good is oft interred with their bones.” Richard’s bones have come back to speak from the grave.

They suggest Richard III was more complex than Shakespeare’s eloquent prose indicates. But they don’t reveal whether he killed his royal nephews. Even so, his bones serve both history and art.