Supporting residency

3/9/2013

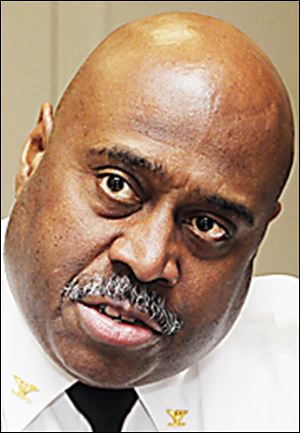

Diggs

Toledo Police Chief Derrick Diggs has embraced community policing as central to his department’s crime-fighting strategy. Toledo police have organized and strengthened neighborhood watch groups, brought city residents into call-in meetings with gang members, and worked with social-service, employment, and education agencies to provide options for young offenders.

The department also has worked hard to recruit a diverse pool of applicants, so that Toledo’s police force more closely reflects the community it serves. Minorities now make up nearly 20 percent of Toledo’s 600 or so police officers, compared with nearly 30 percent of its population.

These efforts will continue to assist Toledo police to reduce crime and violence. Police cannot control crime without the help and support of the community.

Despite these successes, however, Chief Diggs has been virtually silent on another important part of community policing: increasing the number of officers who live in the city. No one would argue that cops who live in the suburbs can’t be outstanding police officers in Toledo. But residency gives officers a greater stake in the community, deepens their understanding of its people and problems, builds relations with residents, and increases the visibility of police in the city’s neighborhoods.

Moreover, the collateral benefits of residency to a large central city that is struggling to maintain its population and middle-class tax base are obvious. The Toledo Police Department does not track how many of its officers live in the city. Police spokesman Sgt. Joe Heffernan said he believes more than half of the department’s officers live in Toledo.

Chief Diggs also lives in the city, but he said little about the issue when he was asked about it during an interview last week with The Blade’s editorial board. He noted, correctly, that courts have struck down residency requirements in municipal employee contracts. Cities, including Toledo, have long abandoned once-common residency rules.

“This issue was settled a long time ago,” Chief Diggs said. “That’s nothing I’m going to touch.” Even so, police chiefs and mayors can still encourage their police officers to live in the city they serve, and provide incentives for them to do so.

In Detroit, about 53 percent of the city’s 3,000 police officers live in the suburbs. Mayor Dave Bing and former police chief Ralph Godbee, Jr. were outspoken on the issue, arguing that it was far better for the city and its public-safety initiatives to have officers living in Detroit. In 2011, the city even started a program that offered assistance to buy tax-foreclosed homes in solid neighborhoods to lure police officers back to Detroit.

Chief Diggs could help bring more of his officers into Toledo simply by talking about the benefits of residency — and that wouldn’t cost the city a dime. Nor does the Toledo police contract appear to prohibit a residency incentive for officers who choose to live in the city, such as a one-time bonus of, say, $1,500.

That’s not a lot. But it would send a message to Toledo’s police officers — and citizens — that their employer places a value on police living in the city whose residents pay their salaries.