Digital justice

4/25/2013

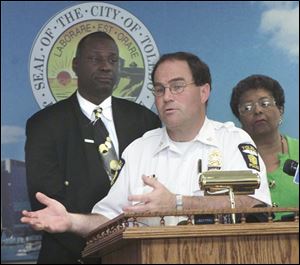

Navarre.

Domestic violence continues to plague northwest Ohio, accounting for much of its violence and, last year, more than a third of Toledo’s homicides.

Police departments still have a long way to go in dealing with this problem. But they have come a long way, as the Oregon Police Department showed this week.

Thirty years ago, police officers often responded to domestic calls by separating the couple and not even making a report.

“We put a Band-Aid on it,”’ former Toledo Police Chief Michael Navarre, who now heads the Oregon Police Department, told The Blade editorial page. “The boyfriend or husband would take a walk or find another place to stay for the night.”

That changed in the 1980s with mandatory reporting. Today, some departments file reports for any domestic dispute. Arrests are mandatory when violence, or the threat of violence, is involved.

Even so, prosecuting domestic cases remains difficult, partly because the victim, almost always a woman, often refuses to cooperate after the initial police call. She may fear for her safety, or genuinely care for the man and not want to see him prosecuted and incarcerated. Tragically, some of these cases end up in a homicide.

Even with an uncooperative victim, police departments can do more to ensure justice and public safety, as the sentencing this week of 23-year-old Cameo Pettaway showed.

Pettaway was arrested on Oct. 14, after assaulting his girlfriend, fracturing her left orbital floor and medial orbital wall around her eye.

He pleaded no contest last month to felonious assault. On Monday, Lucas County Common Pleas Judge Stacy Cook sentenced him to six years in prison.

Last year, Pettaway was acquitted of aggravated murder charges in the 2011 suffocation death of a young couple in Springfield Township.

In this domestic case, as in so many others, the victim refused to cooperate with police and prosecutors, starting the day after the incident, Chief Navarre said.

Pettaway could have skated and, perhaps, committed more violence. But Oregon officers are trained to assume the victim will not cooperate when gathering evidence at the scene.

They use digital cameras to photograph the victim the day of the beating — and the day after, when injuries are often most visually apparent.

They also photograph the scene, documenting any evidence of a struggle: broken or displaced furniture, a knocked-over lamp, pictures off the wall, broken glass.

Using a digital recorder, they get statements from the victim and as many witnesses as possible.

“You anticipate, from the moment you arrive on the scene, that you’re not going to have a victim when it comes time to go to court,” Chief Navarre said. “Our officers are trained to start preparing the case the moment they arrive.”

A team of cops — including officers Jeff Costanzo, Ted Moore, and Scott Wells; Sgt. Chris Bliss, and Detectives Randy Jacobs and Kelly Thibert — assembled compelling evidence for what Chief Navarre calls “victimless prosecution.”

Domestic violence is not just a law enforcement problem, it’s a community problem. But with better police training and a designated domestic violence court docket, communities can gain a stronger partner in overcoming this plague.