EDITORIAL

Buffer zone needed

1/17/2014

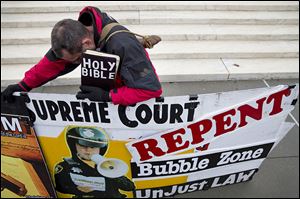

The U.S. Supreme Court heard arguments about buffer zones around abortion clinics. A man from North Carolina makes his point outside the court.

Massachusetts passed a law in 2000 creating a six-foot “floating buffer zone” to provide a bubble of protection around patients and staff entering and leaving abortion clinics.

The law responded to repeated incidents of harassment and violence by anti-abortion protesters at Massachusetts clinics, which included blockading entrances and intimidating those who entered and exited. Far worse, two Boston Planned Parenthood clinic employees were murdered.

Seven years later, witnesses told state legislators the floating bubble didn’t work: Protesters continued to impede access, harass those entering, and crowd and block entrances. It should be noted that many of those entering the clinic were there to get family planning and other medical and health-care services.

The legislature then passed a law setting up a fixed 35-foot buffer, represented by painted arcs around clinics in Boston, Worcester, and Springfield. Protesters must remain beyond them.

The buffer is now being challenged in the Supreme Court, which is scheduled to decide in June. As justices heard arguments Wednesday, they appeared evenly divided.

The buffer-zone challenge comes as abortion rights are under attack, both in Congress and state legislatures across the country. A bill introduced by Rep. Chris Smith (R., N.J.) would expand federal policy banning federal funding for abortion to include any funding, subsidy, or tax credit for plans that cover abortion in private insurance.

The lead petitioner in the case before the U.S. Supreme Court is Eleanor McCullen, a 77-year-old suburban grandmother who quietly approaches pregnant women walking to the Boston clinic and seeks to talk them out of an abortion. She and others who describe themselves as “sidewalk counselors” sued, arguing that the buffer violated their First Amendment rights to peacefully protest and communicate on public streets.

To her credit, Ms. McCullen offers to help patients through their pregnancies, promises to hold a baby shower for them, and with her husband provides them infant-care equipment. She claims to have been successful enough to save the lives of hundreds of babies. That claim, however, precisely negates her argument that the buffer zone keeps her from effectively communicating with the women.

Buffer zones walk a line between First Amendment rights, legitimate privacy rights, and public safety. Still, they are well-established in law and in practice. If this zone is not upheld, the area outside clinics will likely become spots where protesters can once again create havoc and impede a woman’s constitutional right to abortion.

Opponents of the law argue that the buffer impedes the ability of people to freely exchange ideas on public sidewalks. But the statute, as the American Civil Liberties Union notes in its friend-of-the-court brief, is “directed at behavior, not speech.” Outside the buffer, no limit is placed on what the protesters say or how they say it. The issue here is safety and a history of harassment and violence at these clinics.

Massachusetts and other states already create buffers around political conventions, funerals, and polling places — 150 feet for the latter in Massachusetts. Ohio law sets up a 100-foot buffer marked by flags outside a polling place.

Even the Supreme Court has a buffer on the plaza outside its building. Demonstrators must remain on the sidewalk beyond.

If the high court, of all places, surrounds itself with a buffer, clinics that have had a history of undergoing intimidation and violence deserve the same.