Decision had little initial effect in Toledo

5/16/2004

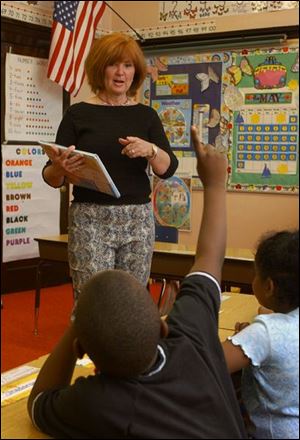

Pam Jackson works in a school system that has seen much change in 50 years since the ruling of Brown vs. Board of Education.

Retired Toledo Municipal Court Judge Robert Penn remembers when he and other attorneys huddled around Thurgood Marshall at the 1953 NAACP convention as Mr. Marshall shared his thoughts about arguing the Brown vs. Board of Education case before the U.S. Supreme Court a year earlier.

Judge Penn had recently finished law school and was handling local cases on behalf of the Toledo NAACP branch. He said he and other young attorneys just wanted to absorb some of Mr. Marshall's wisdom and did not fully comprehend the magnitude of that moment in time.

"The court hadn't ruled on the case yet," Judge Penn said. "[Mr. Marshall] was just talking, and we were all listening. We had no idea, at that time, what an historic event it truly was."

It has been 50 years since the 1954 Brown decision shattered the "separate but equal" doctrine, arguably the most controversial case in Supreme Court history and one that remains a subject of debate over its impact.

For Judge Penn and others in Toledo, the case that shook the walls of racial segregation in the South barely registered a tremor here. Toledo did not have legally segregated schools and facilities but so-called "Jim Crow" practices that were an unwritten fact of everyday life.

"I just knew there were certain places I couldn't go into," Lucas County Common Pleas Judge Charles Doneghy said about growing up in Toledo at the time. "At Libbey, we had no black cheerleaders, majorettes, or anything like that. There were school groups you knew as a black you couldn't join."

Many African-Americans attended Gunckel School, located at Collingwood Boulevard and Nebraska Avenue. Judge Doneghy described the student population as "99.9 percent black." Many African-American teachers got their start as well at Gunckel, which served three African-American housing projects that the Lucas Metropolitan Housing Authority segregated by race.

"We didn't have segregated schools [in Toledo], but we had segregated neighborhoods," said Judge Penn. "Everyone lived in the same place; so we nearly all went to the same schools. When I moved out of the neighborhood in 1964, I needed a white person to buy the home for me. My neighbor came over and told me his property value dropped $5,000 the day I moved in."

Laura Palmer, a retired African-American teacher, moved to Toledo with her husband, Dr. Warren Palmer, an optometrist, right after the Brown decision in 1955. She taught in Virginia the year before, but the Brown decision brought no immediate help to African-Americans there.

"I taught in a two-room school with an outdoor bathroom," Mrs. Palmer said of her Virginia school. "Things were very dif-

ficult. Our books were outdated, and we did the best we could."

She said Toledo schools offered better facilities for black students, including nice classrooms, updated textbooks, and neighborhood schools. For the couple, Toledo proved to be a shelter from the racial divide they experienced in the South.

"[The segregation] just made you feel inferior," said Dr. Palmer, who grew up in North Carolina and met his wife while attending what is now Morgan State University in Baltimore. "You felt that you weren't equal, even though you knew down in your heart that you were."

Students in the predominantly black Spencer-Sharples schools likewise felt unwanted in the 1960s when neighboring school districts did not want to take in the students from the financially struggling school system - one of the 10 poorest in Ohio and one of the worst academically. The high school was not accredited and students were nearly two years below average in achievement.

Toledo Public Schools agreed to take up the challenge, and in 1967 the state board of education gave special permission for Spencer-Sharples students to be taken over by the larger district even though it was separated by several miles.

"It didn't have the size or the resources to support itself," former Spencer-Sharples superintendent Joe Rutherford told The Blade years later.

Meanwhile, deals cut during the 1950s and 1960s, when Toledo annexed large sections of neighboring Washington Township, allowed Washington Local schools to remain independent. Critics claimed township residents were allowed to gerrymander two tiny chunks of the township totaling one square mile so they could legally let the school system exist.

"Having these two school systems is blatantly racist," Lola Glover, executive director for the Coalition of Quality Education, a group representing parents in Toledo Public Schools, told The Blade in 1994.

Last week, Mrs. Glover reflected on the fact that she was a student when the Brown decision was handed down. "Most people felt that it would bring equality and fairness," said Mrs. Glover, whose family moved to Toledo from Mississippi in 1942. "Equity didn't come with desegregation. People thought once we were integrated, equality would come for blacks and whites, and it didn't."

Richard Jackson, a longtime Toledo schools administrator, said he transferred from Gunckel to Monroe School, once located at the corner of Monroe Street and Lawrence Avenue, in 1956. He said that school was racially mixed, and blacks started to have a little mobility.

Mr. Jackson said Toledo Public Schools managed to stay out of desegregation litigation with voluntary plans such as open enrollment, allowing minorities to move to other schools to achieve racial balance, and a desegregation of its faculty and staff in the 1970s.

The late Emory Leverette became the district's first black administrator when he was named assistant principal at Gunckel in 1944. Enrollment drops at the school, which once served as many as 1,700 students in the 1960s, led to a partial closing in 1982 and complete closure in 1989.

Shirley Walker was one of a handful of African-American teachers in Toledo who taught outside of Gunckel. She taught at Washington School, which at the time had a mixture of black and white students. She began splitting time between Washington and Gunckel in the 1940s until Washington had enough students for her to teach there full-time.

Mrs. Walker said she remembered the district hiring many African-American teachers from West Virginia because that state did not allow blacks to teach school. She said she is dismayed by the lack of African-American teachers in Toledo today.

"We had more black teachers [in Toledo Public Schools] then than we do now," she said. "There was a lot of prestige that came with being a teacher back then. We don't see teachers held with that regard today."

Today, Toledo Public Schools, like most urban districts, has become a majority minority district. African-Americans and Hispanics made up 54 percent of the 35,533 students during the 2002-2003 academic year.

"Brown didn't fulfill the promise of equality partly because we didn't hold people's feet to the fire to make sure it was done," Mrs. Glover said. "It sounded good, but we didn't work on how and when."

Contact Clyde Hughes at:

chughes@theblade.com

or 419-724-6095.