Parents, educators embrace new setup

11/21/2004

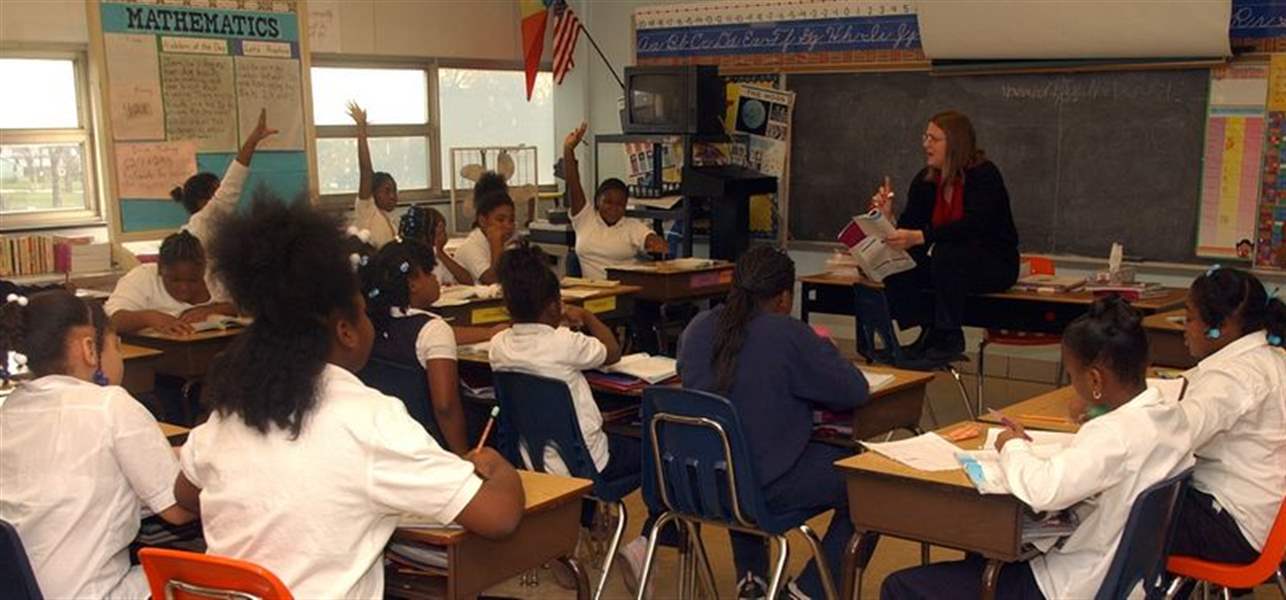

Student participation doesn't appear to be a problem in Barb Bainter's fourth-grade class at the Stewart Academy for Girls.

Hires / Blade

Student participation doesn't appear to be a problem in Barb Bainter's fourth-grade class at the Stewart Academy for Girls.

Seventh grader Kadlyn Rodgers misses just a few things about the traditional school she used to attend, but she doesn't really miss the boys - and certainly not mediocre grades.

For the 12-year-old, the move to Toledo Public Schools' all-female Stewart Academy for Girls was a joint parent-child decision and also a no-brainer.

"I've gotten way better grades since I've been at Stewart - way better," she said of the school at 707 Avondale Ave.

Just a mile and a half away at Lincoln Academy for Boys, 11-year-old Marvin Brown thought his mother was kidding last year when she told him he'd be going from Toledo Public's King Elementary to the district's new all-male elementary school at 1801 North Detroit Ave.

TPS and its 34,000 students were thrust into the national limelight in 2003 when Superintendent Eugene Sanders announced it would join a short list of communities with single-gender public elementary schools. A provision of the federal No Child Left Behind Act allows school districts to establish single-gender schools and classrooms.

Though now a growing trend around the country, the transformation to single-gender schools in Toledo initially drew a mixed bag of skepticism and support from parents.

Fifteen months after taking two low-income, neighborhood schools with problems like fighting, poor attendance, and poor academic performance and converting them to single-gender schools, both high ranking district officials and classroom teachers say they've seen some results that indicate the concept is working.

"I think that the first year, there was a fair amount of excitement because they were new," Mr. Sanders said. "This year the focus has shifted dramatically to significantly improve test scores and I think both schools are set up to do that, now that parents' panels are in place and that the rules have been fully communicated with parents."

As the former Stewart Elementary School, the average passage rate on proficiency and achievement tests for the 2001-2002 school year was just 17.2 percent. The following year, the rate rose to 27.5 percent. Last school year, as the new Stewart Academy for Girls, it went up again to 34.1 percent.

As the former Lincoln Elementary School, the average passage rate of proficiency and achievement tests for the 2001-2002 school year was just 19.7 percent. The following year, the rate was 23.5 percent. After the conversion last year to Lincoln Academy for Boys, the score last year rose again to 32 percent.

"There is some evidence of improvement, but it is not as dramatic as I would like to see," Mr. Sanders said. "I do think it's a kind of environment that can provide some pretty significant results."

Walking through the halls of Stewart, it's easy for anyone familiar with the building to see how a child would have fewer distractions - the volume levels in the classrooms and hallways are way down from when it was co-ed.

"It's very quiet here now since it's just the girls," said Laura Hixon, a first-grade teacher at Stewart. "There are some days that it's difficult to deal with their moods, but the girls are generally caring and very sensitive to each other."

Meanwhile, over at Lincoln the chit-chat is at a healthy decibel.

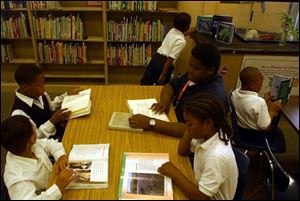

Students at Toledo Public Schools' Lincoln Academy for Boys spend some quiet time with books in the school's library.

"Boys are louder and need more physical interaction," said Su Breymaier, a Lincoln sixth-grade teacher. "Boys feel they have to perform for girls and without girls here, they have a comfort zone in which they can be themselves."

Girls in a single-gender educational settings are more likely to take classes in math, science, and information technology. Boys in single-gender schools are more likely to pursue interests in art, music, drama, and foreign languages, according to the National Association for Single Sex Public Education.

Teachers tend to agree.

"The girls don't seem as shy in class, especially in math," said Becky Henry, also a first-grade teacher at Stewart.

Rosalyn Hands enrolled her sixth-grade son at Lincoln last year without hesitating.

"I thought the concept was good because boys do have their own issues that need to be addressed and when girls are in the mix, their issues tend to be pushed aside," Ms. Hands said. "Somewhere along the line, boys lose interest in education You can see here that they are feeling their ways in society and how they should be acting as men."

Teachers at Lincoln admit they had a rocky start.

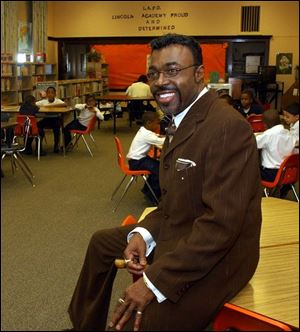

There were practically no changes in the school's curriculum or discipline standards when the building changed to all-male. But this year, it undertook an innovative discipline program that promotes "responsible thinking" and instilled the concept of being a team for each classroom where the teacher is the coach, Principal Derrick Roberts said.

"Behavior was my immediate concern," Mr. Roberts said. "We are teaching them how to work together and be leaders. We are also getting them to think that actions have consequences."

Behavior at both schools has improved dramatically, teachers said.

"This was a rough school," said Ms. Hixon of Stewart Academy. "There is definitely more structure and we don't have the type of problems like fights, which we had even in the first grade."

When the school year resumed after summer break last September, Stewart was Ohio's only all-girls public school, while Lincoln was one of just four public schools for boys, according to the state Department of Education.

'Behavior was my immediate concern,' says Derrick Roberts, principal of the Lincoln Academy for Boys. 'We are teaching them how to work together and be leaders. We are also getting them to think that actions have consequences.'

Although the schools gained a lot of attention, neither Stewart nor Lincoln has come close to enrollment capacity. District officials said last year that each school could accommodate up to 500 pupils, yet Stewart has about 350 students and Lincoln has just under 300 - not much different than their enrollment before the single-gender switch.

Mr. Roberts, Lincoln Academy's principal, said both schools will probably see increases in enrollment over time "as they become more established," he said.

Stewart has grades kindergarten through seven and Lincoln hosts kindergarten through six. Many of the other single-gender schools across the nation are for middle school and high school, according to the U.S. Department of Education.

All-boys and all-girls private and Catholic high schools have commonly existed for many years, but now more public school districts are experimenting with the concept, said Rosemary Salomone, author of Same, Different, Equal: Rethinking Single-Sex Schooling.

"We know for sure the single-sex schools do not harm children, and there is some evidence that [children], particularly girls, can achieve in that environment," Ms. Salomone said. "There is a study that came out of Catholic schools in the 1980s that showed girls and minority boys in single-gender schools showed higher achievement gains and higher self esteem."

Students at the Stewart and Lincoln are more than 95 percent African-American, according to district records.

Mr. Sanders said he believes the all-boys school will show that the single gender atmosphere can increase graduation rates among African-American males. "We will be able to track these students through middle school and high school and be able to say the percentage of boys from [Lincoln] who graduate high school was 80 or 85 percent, rather than 65 percent," Mr. Sanders said.

Contact Ignazio Messina at: imessina@theblade.com or 419-724-6171.