EDUCATION MATTERS: One in an occasional series

Chattanooga district may offer TPS lessons

Focus on teachers yields gains for students

6/12/2011

Emily Baker, principal at East Side Elementary in Chattanooga, Tenn., talks with a parent who was collecting her child’s report card on the last day of school. Ms. Baker says the school was a mess when she took over in 1997.

CHATTANOOGA, Tenn. — Set in the Appalachian Mountains along the Tennessee River near the border of Georgia and Alabama, Chattanooga doesn’t look much like Toledo.

With thick southern accents and a conservative strain, it doesn’t sound much like Toledo either.

But what educators learn in this southeast Tennessee city may be valuable lessons for northwest Ohio. Chattanooga, like Toledo and most other urban school districts, suffers from the doughnut effect — a circle of high performing, wealthy schools surrounding high poverty, central-city schools that score abysmally.

A decade ago, many Chattanooga teachers were burned out, inexperienced, or simply not up to par. Their students were highly mobile, lived volatile lives, came into school behind wealthier peers in basic skills, and didn’t have the support at home many other students get.

SEE MORE:

District helps principals hone leadership skills

Those factors heavily influence student performance on standardized tests that assess as much of what a student has lived as what they are taught in the classroom. Schools can’t control those factors. Chattanooga school leaders focused on what they could control: teacher quality.

“The most important variable to improve student achievement is teacher quality, and effective instruction,” said Susan Swanson, director of urban education for the Hamilton County (Tennessee) school district, which includes Chattanooga.

Those who knew Chattanooga’s central-city schools knew they were in bad shape. It wasn’t until the schools were ranked that they realized the depth of the problems.

An independent research group ranked Tennessee’s elementary schools in 2000 based on standardized state test scores. Of the 20 lowest-rated schools, nine were in Chattanooga. The reaction by most in the community was muted.

“You would think there would have been shock, outcry,” said Clara Sale-Davis, who works for a Chattanooga foundation involved with turning the city’s schools around. “People expected them to fail.”

But for some, there was shock. They didn’t accept that the schools couldn’t excel. Ms. Sale-Davis slams her hands onto her knees when she talks about the failure to educate the most vulnerable children.

“We’ve allowed malpractice to continue,” she said. “We’ve hidden malpractice in schools of poverty.”

A group of district leaders joined with two private foundations in Chattanooga — the Benwood Foundation and the Public Education Foundation, which put up millions of dollars for something called the Benwood Initiative.

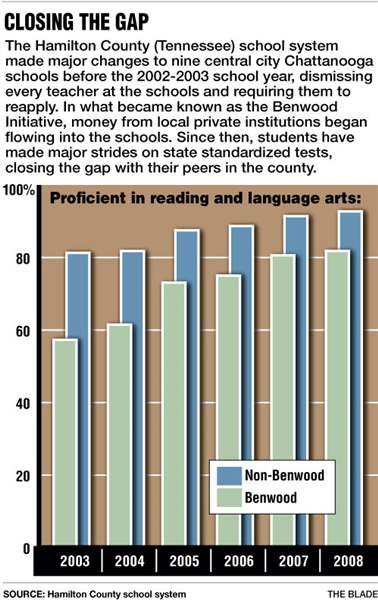

When it began, the gap between the schools in the program and the rest of the county’s schools seemed insurmountable.

More than 42 percent of Benwood students were not proficient in reading in 2003, compared with about 19 percent of non-Benwood students. By 2008, nearly 82 percent of students in Benwood schools were scored as proficient in reading, only 11 percent less than non-Benwood students.

Clara Sale-Davis, director of the Benwood Initiative for Public Education Foundation, addresses fifth-grade teachers who gathered to swap advice on test preparation.

The teaching staff at all nine schools was reconstituted: All teachers had to reapply for their jobs at the schools. In a collaborative move, the teachers’ union signed off on the reconstitutions and other controversial measures. Teachers who excelled and schools that showed gains qualified for bonuses. Parallel initiatives offered teachers paid tuition to obtain master’s degrees.

But at the core of Benwood’s success, according to the teachers and administrators in the schools, were three constants: accurately evaluating teacher quality, providing support to improve teachers, and holding them accountable. In short, make teachers better.

Focus on data

When kindergarten teacher Patricia Clark arrived at East Side Elementary nearly two decades ago, the program was mostly based around teaching children social adjustments.

“If they didn’t know all the letters,” Ms. Clark said, “it wasn’t that big of a deal.”

Now, kindergarten teachers have color-coded charts, showing in what month each student learned a particular letter of the alphabet.

She continuously tracks her classroom’s mastering of the ABCs throughout the year. She can see, just by color, how many students are likely to struggle in first grade.

The Benwood Initiative has a heavy data focus.

After the Hamilton County district reconstituted staff in 2003 at the Benwood schools, about two-thirds of the teachers let go in the reconstitution were hired back. The majority of the schools’ success hasn’t come from finding better teachers, but from improving those already there.

“An effective teacher is one who has a relationship with a kid,” Ms. Swanson said, “and helps that kid to grow at least a year in academic growth.”

While the district uses a variety of assessment tools and teacher evaluation criteria, Hamilton County has become in many ways the epicenter of the value-added movement. Value-added is a system that attempts to assess whether a student learned as much over a given year as expected, using a student’s prior scores.

The focus on value-added assessment isn’t surprising. Tennessee is a pioneer in the use of it; the system used by Ohio is modeled after Tennessee’s, which was developed by then-University of Tennessee professor William Sanders.

The value-added approach is growing in popularity, but it’s controversial. Some statisticians argue the measurement doesn’t take into account the realities of a classroom. But a school has to measure effectiveness somehow.

“A kid who is a year behind, if they don’t get at least a year’s growth, they’ll never catch up,” Ms. Swanson said.

Learning together

Before the Benwood Initiative, the district provided teachers annually with two days of professional development. The training was broad and often didn’t apply to classroom realities.

Benwood teachers get extra professional development, tailored to school, even classroom, needs. Every teacher has data on how students are progressing, and they know where they most need help.

The foundations pay for national experts to come to the schools, teaching new techniques in small groups that the schools themselves asked for. But the training is worthless if there’s no follow up.

“Just doing professional development is a waste of money,” Ms. Swanson said. “What we need is a system where you learn best practice and then use them.”

At the outset of the Benwood Initiative, each school added an assistant principal, splitting the role between two people. The other half of the pair’s day was spent in classrooms, observing teachers and giving constant feedback.

Each school was given “consultant teachers,” math and reading teachers deemed highly effective, who worked with teachers one on one. They’ve proved they can raise students’ test scores, and now they help the rest of the staff raise their game, teaching them new techniques and pointing out weak spots.

Emily Baker, principal at East Side Elementary, called it job-embedded professional development.

After a 2000 report ranked nine of Chattanooga’s schools as some of the worst in the state, local school leaders partnered with two private Chattanooga foundations — the Benwood Foundation and the Public Education Foundation — in an effort to turn the schools around.

The three entities developed a plan to reform the schools that focused heavily on analyzing data and providing professional development to improve teacher quality. They called it the Benwood Initiative.

The two foundations agreed to contribute up-front costs for the program — about $7.5 million.

The Hamilton County school district (Chattanooga’s school system merged with the county’s in 1997) then launched a variety of efforts, working in concert with the two foundations.

All teachers at the schools, along with most of the principals, were removed. The teachers had to reapply for their jobs at the schools.

Each Benwood school received yearly financial support, generally about $130,000, to spend as they chose. Schools hired additional staff and bought much needed material. The foundations also paid for national consultants and experts to train teachers.

At the same time, parallel initiatives provided financial incentives in an attempt to recruit and retain quality teachers. Teachers who moved near Benwood schools received forgivable loans for part of the purchase of a house. Teachers were offered paid tuition to obtain master’s degrees.

Teachers whose students showed significant academic growth qualified for financial bonuses.

The initiative showed almost immediate success. Reading and math scores have improved greatly, and the gap between central city students and their suburban peers has shrunk.

“We go into each other’s classrooms and learn from each other,” she said.

Several doors down from her kindergarten classroom, through a hallway lined with elaborate paintings of animals, Ms. Clark gathered on a late May day with other teachers. The year was winding down, and the conversation was less structured than it usually is. For most of the year, this is where they learn to teach.

Teachers in each grade level at East Side plan together, 30 minutes a day, four days a week. They use the time to discuss data and bounce ideas off each other.

It’s not a free-for-all. Teachers have to fill out a planning book that details what was discussed and how it fits into the goals for improvement. The principal has to sign off on the book.

Maybe a young teacher will admit he’s struggled teaching a group of students to decode words. Ms. Clark might offer to peer-model a new technique. It’s the kind of support many teachers, door closed and on their own island, never get.

“That’s huge, especially for a new teacher,” Ms. Clark said.

Taking the lead

Emily Baker reconstituted her school before anybody told her to. The diminutive woman in 1997 took over East Side Elementary, a poor school with a large Guatemalan population set along the city’s “Prostitution Row.”

The school was a mess when she came, she said. Her teachers hardly ever brought their A game to work, she said, and some had attitudes toward their jobs that were “borderline criminal.” Students, and parents, were out of control.

Ms. Baker put in new standards and behavior expectations. Many teachers didn’t like it. Each year, a handful left for another school. That was a good thing, she said.

“I don’t play when you are dealing with the lives of children,” Ms. Baker said.

With the constant feedback in the Benwood Initiative, teachers know how they are performing. It’s up to administrators to make sure they improve.

In the Benwood Initiative, tenured teachers who were not effective would be put on notice and observed regularly in the classroom by administrators, Deputy Superintendent Ray Swoffard said. If the teacher didn’t improve, that person was asked to retire or resign. The district always had the process in place, but with Benwood, school district officials actually used it.

“A lot of administrators don’t want to make discipline decisions with a teacher,” Mr. Swoffard said.

In coming years, the teachers won’t be asked to step down. Under a new Tennessee evaluation system being piloted in elementary schools such as Red Bank, tenured teachers could lose their jobs if they consistently underperform. Value-added assessment is a major component — about 35 percent — of a teacher’s evaluation.

No ‘silver bullet’

Building layouts, curriculum models, and classroom techniques can have positive or negative impact on student achievements.

But what the Benwood Initiative shows is that quality teaching and quality leadership are paramount.

“This is not the silver bullet,” Ms. Sales-Davis said. “It’s ammunition for school improvement.”

Hamilton County (Tennessee) School District

2010-2011

Students: 42,000

Percent minority: 40 percent

Economically disadvantaged (2009-2010): 60 percent

Schools: 73

District area: Approximately 540 square miles

Expenditures per student (2009-2010): $9,220

Average teacher salary: $46,000 (not including benefits).

Toledo Public Schools

2010-2011

Students: 25,000

Percent minority: 60 percent

Economically disadvantaged (2009-2010): 67 percent

Schools: 53

District area: Approximately 80 square miles

Expenditures per student (2009-2010): $13,544

Average teacher salary (2009-2010): $54,568 (not including benefits).

Officials tried a new technique this year, placing math and reading coaches in one classroom in Benwood buildings, team-teaching for half the day.

During the other half, they’re coaching other teachers.

But splitting the teachers’ duties between the classroom and coaching hasn’t been as effective as hoped, and the district is planning to scrap the idea.

As Red Bank reading coach Roxanne Anthony left her shared fourth-grade classroom, math coach Sandi Fain lit up a screen with a ceiling-mounted projector, math questions illuminated in front of the class.

A boy worked through a multiplication problem with a technique different from others. Ms. Fain presented his method to the class.

“Did it take any longer?” Ms. Fain asked her class.

“No!” they responded in unison.

“Did they get the same answers?” she asked next.

“Yes!” they said. Ms. Fain smiled, and turned back to the screen.

“Then they’re just strategies,” she said.

Contact Nolan Rosenkrans at: nrosenkrans@theblade.com or 419-724-6086.