TPS implements preventive approach to student discipline

5/4/2014

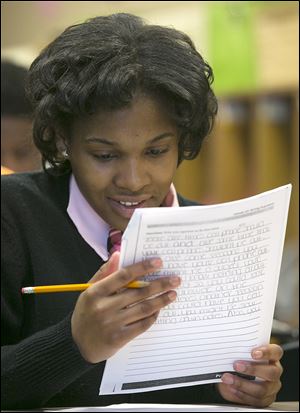

Teacher Tracey Johnson helps eighth-grader Demarko Craig prepare for an upcoming test at Chase STEM Academy. The school expelled Demarko last year for discipline problems. This year is different.

THE BLADE/ANDY MORRISON

Buy This Image

Teacher Tracey Johnson helps eighth-grader Demarko Craig prepare for an upcoming test at Chase STEM Academy. The school expelled Demarko last year for discipline problems. This year is different.

Chase STEM Academy gave up on Demarko Craig once.

He was suspended repeatedly last year. Acting out, being disruptive, not following directions. Demarko doesn’t deny that he was a class clown. He’d act out to get a rise out of students and staff in class. With just a few days left in the school year, administrators had enough.

“They said they were tired of me,” Demarko said. He was expelled.

Demarko, an eighth-grader at North Toledo’s Chase, regrets how he acted. But he also regrets that he never had anyone to talk to about why he acted out. If he got in trouble, he said, they simply sent him home. No discussion.

PHOTO GALLERY: Click here for more photos from STEM Academy

This year is different. Demarko hasn’t been kicked out of school. There’s discussion, instead. A new principal, Jack Hunter, didn’t just treat him differently. He thought of him differently. Mr. Hunter never even looked at Demarko’s file. Everyone got a clean slate.

Chase eighth-grader Cylenthia Pickett looks over her work. Cylenthia was kicked out of school and arrested for fighting last year. She knew she did wrong. ‘I thought I was big and bad.’

“He told me I wasn’t going to be like I was before,” Demarko said.

Student teacher Tara Smith, a student at the University of Toledo, helps eighth-grader Willie Mullins with his work at Chase STEM Academy. A core element of the support program is teacher buy-in.

This year, Demarko has not been suspended. He hasn’t even been referred for discipline.

Toledo Public Schools has made a concerted effort in recent years to overhaul its discipline program, reducing the number of students suspended and expelled. In many ways, it’s worked: Total suspensions and expulsions in the first semester this year were about half what they were in the 2009-2010 school year.

The district is implementing the Positive Behavior Interventions & Supports program, which is meant to improve school environments, reinforce positive behavior, and teach appropriate action to students through a preventative approach to discipline, rather than a reactionary one.

“We are happy about the progress we are making, but we know there’s still more work to do,” TPS Chief Academic Officer Jim Gault said.

A sign counts how many days have been lost because of suspension this year at Chase STEM Academy in Toledo. Last year, 260 days were lost by this time.

‘Love and logic’

Inside the data is a persistent problem. African-American students are suspended and expelled at three times the rate of white students. Most suspensions aren’t for violent incidents, but for classroom disruptions. High discipline rates rob students of classroom time, develop distrust among students, families, and schools, and can give the perception of racial bias.

It’s a trend seen across the country. Most suburban schools also have similar discipline disparities.

And what may be most frustrating — but at the same time offer a glimmer of hope — is that TPS has what appears to be the answer staring it in the face. That answer may be schools such as Chase, where discipline problems have nearly evaporated.

Suspensions at Chase have dropped dramatically this year. While students had lost 260 days to suspensions at this time last year, that number has dropped to 41 this year. No students have been expelled. The school has rejected, both in action and in mentality, a punitive discipline approach that has led to high discipline rates that have disproportionately affected minority students.

The new approach, using “love and logic,” hasn’t just led to less official discipline actions, staff said, but a better school environment that needs less discipline.

“If I send a kid out of my office angry, they take it out on the teacher and the classroom,” Mr. Hunter said.

Chase is one of more than a dozen TPS schools that has implemented the new approach.

While the general philosophy is the same, each school building using the program has its own individual approach. Mr. Hunter left teaching for a time to work in the automotive industry and venture capital, and he says he runs his school like a business. Students and parents are his clients.

A large part of his philosophy is giving students a voice. When they get in trouble, the first conversation isn’t about how they’ll be punished, but is an opportunity for students to explain why they acted the way they did. Almost every time, students can explain what they did wrong.

The idea is to mentor kids, not to punish them. Students are taught proper behavior, not reflexively punished for not understanding a school’s boundaries or expectations.

“Threatening kids never works,” Mr. Hunter said.

Some of the changes seem so simple, and yet drastic. Chase did away with detentions. A demerit system, where students were constantly reminded of their errors as part of “progressive discipline,” was ended. Staff found the practice an unnecessary focus on negative actions.

“It seemed petty,” Chase teacher Tracey Johnson said.

Instead, the school focuses on providing fun, yet educational, activities for students that are incentives for good behavior. The school’s science, technology, engineering, and math offerings were expanded under Mr. Hunter. Students now can do computer programming, participate in Lego League, or the stock market club.

“Kids work for rewards,” Mr. Hunter said.

Hunter

Teacher buy-in

A core element of the behavior support program is teacher buy-in. The best systems in the world don’t work without the right people, Mr. Hunter said. Chase works because of the staff, he said.

Staff must vote to accept the program in the school. While an extra administrative hurdle, it makes teachers invested in the concept. Ms. Johnson is an advocate; she teaches eighth grade and is the school’s teachers union representative.

The whole school atmosphere is better this year, she said. Kids want to be in class.

“We used to spend our time only focusing on the negative,” she said. “We focus more on what students do right than on what they do wrong now.”

Much of Mr. Hunter’s philosophy is born of personal experience. As a student, he got in trouble in school, and he still resents the way he was treated.

“I used to be belittled by teachers,” he said.

He looks back now, and finds the approach ineffective.

TPS wants to soon bring the program to every school. District leaders see success in school with strong leaders who have implemented the program with enthusiasm. But the progress at times seems slow, with some schools showing success, then lagging behind after a few years.

“We are trying, and we are seeing pockets of success with that,” Mr. Gault said. “The key is it’s pockets, we are striving to turn around the district one school at a time.”

Mr. Gault blames some of that on transiency, both with staff and students. Many central city schools have nearly wholesale changes in students and staff over a two to three-year period. That means that many schools are essentially starting from scratch each year.

“Leadership of the building matters, stability of the staff matters,” he said. “And if you have a lot of transiency you are in some cases going back to the drawing board.”

Superintendent Romules Durant says the discipline disparity has decreased in recent years, and the district has targeted the schools with the highest disparity rates for the positive behavior program.

While district leaders say they embrace the philosophical change at Chase, they’ve also had outside pressure.

A committee formed in 2008 by then-board of education member Jack Ford investigated the high number of students out of school for discipline problems.

Advocates for Basic Legal Equality Inc., Toledoans United for Social Action, the African-American Parents’ Association, and others pushed for changes in the district to reduce the racial disparity and how TPS approaches discipline.

And the U.S. Department of Justice’s Civil Rights Division and the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Northern District of Ohio opened an inquiry in 2011 into allegations of “significant racial disparities” in student discipline at TPS. Justice Department spokesman Mike Tobin said the investigation is ongoing.

TPS has worked with community organizations, including critics, to help improve its discipline approach, Mr. Gault said. ABLE, Toledoans United, and others advocated for the program.

The Rev. Dennis Payne of Toledoans United, who is pastor of Monroe Street United Methodist, said that TPS has made improvements, though more work needs to be done. It seems as though the school district is open to change and to working with others, he said.

“The school system is telling us it is a problem that leaves them vulnerable,” Pastor Payne said. “My hats are off to the superintendent for even admitting there is a problem.”

Durant

Discipline rates

Racial disparity in how discipline is meted out is not just a TPS problem.

The issue has found the national spotlight after the Obama Administration issued reports and statements about the high rates of discipline for minority students. The U.S. Department of Education’s Office of Civil Rights found that African-American students are more than 3.5 times as likely to be suspended or expelled as white students.

Most, but not all, suburban Toledo school districts discipline minority students at higher rates than white students.

Springfield Local Schools, for instance, disciplined African-American students as frequently as TPS did last year.

The Maumee district, according to state data, disciplineed African-American students about six times more frequently than white students. That was the largest disparity among sampled Toledo suburban school districts.

Joe Taylor, Maumee’s director of educational services, said discipline rates were declining in the district overall, and the school system is implementing new programs, such as the behavior support program, to continue to improve.

He believes the district’s staff has all students’ best interests at heart.

“We want to see positive outcomes for all of our kids at all of our buildings,” he said.

Few educators these days say, or believe, that they treat students differently based on race or socioeconomic status.

But Ohio State University’s Kirwan Institute for the Study of Race and Ethnicity cites “implicit bias” as a major factor in the disparity in discipline rates. The institute references a study by the Indiana Education Policy Center, which states there is no support for the belief that African-American students act out more than other students.

“Rather, African-American students appear to be referred to the office for less serious and more subjective reasons,” according to the Indiana study.

That’s backed up by data. The vast majority of African-American students who are disciplined in the Toledo area are not accused of violence, drugs, or other serious infractions. Instead, they’re suspended for disobedience, disruption, or disrespect.

“If a white child is a little bit aggressive or acts out in a certain way, that sometimes is perceived as that child being ambitious or creative or thinking for themselves,” said Robert Cole, an ABLE attorney. “When a black child does it, it’s viewed as a challenge of authority.”

That most teachers are white may also play a factor.

The Kirwan Institute says research shows that African-American teachers generally rate African-American students’ behavior more favorable than white teachers.

Toledo Public Schools has faced calls for years, possibly most vocally from the African-American Parents’ Association, to diversify its teaching and administrative ranks, which are weighted significantly toward white teachers and principals.

Mr. Durant places less weight on the race of teachers, and more on if they can culturally relate to their students. There are black teachers from the suburbs who can’t relate to students from rough neighborhoods. Mr. Hunter, he pointed out, is white.

“The only time race matters is when I first look at you,” Mr. Durant said.

Urban schools tend to have less seasoned staff who have had little training or experience working with or even relating to children and families from high poverty areas. A year of student teaching isn’t enough, he said.

There should be more preparation for teachers when they come into urban schools, he said. Mr. Durant also said he hopes to create a teaching pipeline from the district’s own students. Who better to relate than graduates of the same school?

Mr. Durant also pointed to the lack of student preparedness, with many coming into kindergarten behind peers and lacking social capital. A beefed up Head Start program should help, he said.

While zero-tolerance policies play a role in discipline disparity, the institute also cites “implicit bias,” or the “mental process that causes us to have negative feelings and attitudes about people based on characteristics like race, ethnicity, age, and appearance.”

The institute references a study that found that “teachers perceived students with African-American culture-related movement styles as lower in achievement, higher in aggression, and more likely to need special education services ...”

Another chance

At Chase, the idea is not to write students off after they’ve made mistakes. Given a chance, most students accept consequences and want to do right.

Cylenthia Pickett, 14, knows she made a mistake last year. A dispute with a younger girl escalated, she said, after friends egged on the disagreement. Words were exchanged, and the pair fought outside school. Later that day — and she says unbeknownst to her — Cylenthia’s friends tracked the girl down and severely beat her. That incident was caught on camera outside Chase.

Those girls were arrested, and so was Cylenthia for the initial fight. She was kicked out of school for the rest of the year and spent time in juvenile detention.

No one needs to tell her what she did was wrong. She’s embarrassed, she said. She should have walked away.

“I thought I was big and bad,” she said.

That fight could have pegged her as trouble for the rest of her life. Instead, Chase points to her as an example of the new way at the school. She’s getting good grades this year, and hasn’t been in trouble. She’s involved with the Young Women of Excellence program.

“It helps me calm down, and it helps me remember who I really am,” she said of the group.

Demarko is involved with the Young Men of Excellence. Once, kids followed his lead and acted out in class, he said. Now, they follow his lead and want to play football in high school.

Contact Nolan Rosenkrans at: nrosenkrans@theblade.com or 419-724-6086, or on Twitter @NolanRosenkrans.