EPA orders bigger cuts in emissions

New goal for coal plants is raised to 30% by 2030

6/1/2014

The Obama Administration will unveil a plan Monday to cut earth-warming pollution from power plants by 30 percent by 2030, according to people familiar with the proposal.

WASHINGTON — The Environmental Protection Agency will propose a regulation today that will cut carbon-dioxide emissions from existing coal plants by up to 30 percent, compared with 2005 levels, by 2030, according to individuals who have been briefed on the plan.

The draft rule would give states and utilities four options of how to meet the new standard, with emphasis on energy efficiency, shifting from coal to natural gas, investing in renewable energy, or discounts to encourage consumers to move to off-peak hours.

The rule represents one of the most significant steps the federal government has ever taken to curb the nation’s greenhouse-gas emissions, which are linked to climate change.

The plan is expected to spark a major political and legal battle.

President Obama called a group of Senate and House Democrats on Sunday to thank them for their support in advance of the proposed rule, according to a White House official who asked for anonymity.

Ever since a climate bill stalled in the Senate four years ago, environmental and health activists have been pressing Mr. Obama to use his executive authority to impose limits on the power sector, which accounts for 38 percent of the nation’s carbon-dioxide emissions.

Opponents — including coal producers, some utilities, and many Republicans — argue that the EPA is using a novel legal approach to demand greenhouse-gas cuts that are not achievable given current technology.

It is unclear whether the proposal ranks as Mr. Obama’s most sweeping climate policy because the plan would cut 500 million metric tons of carbon dioxide by 2030.

Previous measures to strengthen fuel-efficiency standards for cars and light trucks will cut 2.9 billion metric tons by 2050.

“This momentous development raises the bar for controlling carbon emissions in the United States,” said Andrew Steer, president of the World Resources Institute.

Mr. Steer said that “many states are well-positioned to meet or exceed the proposed carbon reductions through existing infrastructure and policies that are already in place.” He said the proposed standards “give states flexibility to implement plans according to their needs.”

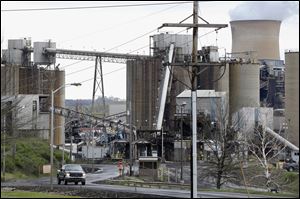

Much of the electricity sector’s carbon pollution stems from aging, coal-fired power plants.

The average U.S. coal plant is 42 years old, according to the EPA, meaning that most of them aren’t nearly as efficient as new ones, though many have been updated.

Some were built when Dwight D. Eisenhower was president, according to Exelon chief executive Christopher Crane.

The regulations could affect natural-gas-fired power plants, which emit about half as much greenhouse gas as coal plants.

The EPA said that natural-gas-fired combined-cycle plants in the United States are 14 years old on average.

The EPA plan resembles proposals made by the Natural Resources Defense Council, which would allow states and companies to employ a variety of measures — including new renewable-energy and energy-efficiency projects “outside the fence” or away from the power-plant site — to meet their target.

This approach aims to keep consumer electricity prices from rising too sharply as a result.

Usually when the EPA regulates pollutants under the Clean Air Act, the agency sets an emissions limit for each facility.

By contrast, under a “mass-based system,” states would have to meet an overall target for greenhouse-gas emissions and ensure that power plants either make those reductions at their facilities or finance efforts to achieve them in other ways, such as by reducing consumer energy demand or investing in carbon-free electricity generation.

Meeting the EPA targets might not be difficult for states that have cut carbon-dioxide emissions in the electricity sector or that have been meeting their own renewable energy standards.

Since the EPA proposed baseline year of 2005, 13 states and the District of Columbia have cut carbon emissions by about 30 percent or more, according to a Sierra Club compilation of Energy Information Administration data.

Daniel Fiorino, who directs American University’s Center for Environmental Policy, said that using this approach is “a really nice example of smarter regulation” because it gives firms and state regulators greater leeway in how they would meet a federal standard.

But Mr. Fiorino, who worked at the EPA for 31 years and served in the agency’s office of policy analysis, added, “When you have flexibility, there’s potentially more room for a legal challenge.”

Several coal industry and business officials have questioned the Obama Administration’s approach, saying it will cost coal miners their jobs and could lead to electricity shortages.

The Electric Reliability Coordinating Council, a lobbying group that represents energy companies with major investments in coal-fired power plants, has prepared an analysis that cites a study estimating that a phase-out of coal plants could cost consumers $13 billion to $17 billion a year between 2018 and 2033.

“There are no off-the-shelf technologies to address carbon, only fuel-switching regardless of expense or energy rationing,” the group writes.

The U.S. Chamber of Commerce has commissioned a separate study, projecting that the rule could cost the U.S. economy an average of $50 billion a year during the next 16 years.

Supporters of the administration’s proposal, meanwhile, argue that it will save Americans money because of the public-health benefits that result from cutting power plants’ soot and smog-forming pollutants.

Moreover, they say, renewable energy has become increasingly competitive with fossil fuels.