WEED IT & REAP

Michael Horst makes time for an urban farm

8/20/2014

Pekin ducks drink from a baby pool.

THE BLADE/LORI KING

Buy This Image

Pekin ducks drink from a baby pool.

Michael Horst in his backyard garden in Toledo.

Not fussy about weeds, Michael Horst’s vegetable patch is a bit out of control. He planted in May, then went to India for a few weeks and the weeds got a foothold.

Adding to the chaos, he tossed outdated seeds, some marked for use as long ago as 2008, into the patch.

“A lot of stuff came up. I keep finding surprises,” says Horst. Seeds beyond expiration date can still grow, but with lesser viability. He obtains free seed packets at the annual Seed Swap organized by Toledo Grows.

PHOTO GALLERY: Mike Horst‘s urban garden

And then there’s the buckwheat seed he’s thrown down to fix nitrogen in the soil, an idea he got from a Namibian soil scientist who “told me to always keep a live root in the soil. I’ve since been cover-cropping more.” Nitrogen in the soil is essential for green leaves, new roots, and shoots.

Horst loves trying new things and his hobby farm is an endless experiment. He lives in a quiet neighborhood of “young families, retirees, and lunatic farmers like me” near Reynolds Road and Bancroft Street.

A 2004 Northview High School and 2008 University of Dayton grad, he works at the heating and air conditioning company his father bought 22 years ago. He coaches and plays lacrosse, does blacksmithing at the Toledo Museum of Art, hunts, plays bass, and rents rooms in his home, sometimes showing visitors the town.

Behind the little white house he shares with Duke, a black lab, and a bunny, is a sunny yard, 260-feet-deep by 100-feet-wide. Rain water from the roof funnels through the downspout and then underground through a perforated pipe to a rain garden.

“It slows water down and supports pollinators like the monarch while reversing the flooding action of the Lake Erie watershed and subsequent algae blooms.”

The yard’s back section no longer floods because he’s built it up with about four inches of mulch. Compost piles, hidden by trees and bushes, are in the way back.

Raspberries.

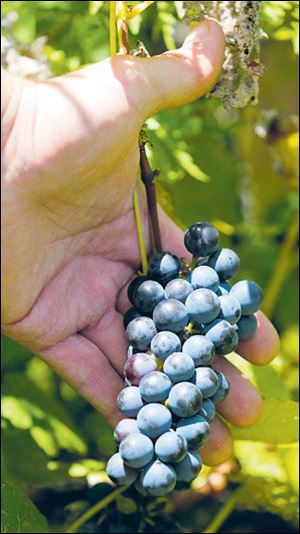

It’s his fifth gardening year here. Behind a fenced group of veggie patches (30-by-25-feet) is the young orchard. Fruit-tree saplings he planted last fall and this spring are healthy and four- to seven-feet tall. Concord grapes cling to a fence.

Concord grapes.

“I eat all I can and give a lot away. What you can’t eat right away you can freeze, can, dehydrate, and dry. I canned tomatoes last weekend.”

Giant pumpkin vine snakes across the lawn.

He’s had four chickens for two seasons years and added three this spring. Their breeds are dorking (they date to the Roman Empire), sussex (date to the time of the Roman conquest of Great Britain), andalusian, Rhode Island red, golden comet, and two Plymouth rocks, which have extra-large eggs.

The birds inhabit two movable coops and Horst moves the smaller, four-by-eight-foot coop as often as twice a day to provide the birds with fresh peckings. If he wants them to help prepare a new garden bed, the coop may remain in place for a longer period.

All four chickens survived the winter in an unheated box. Instead of removing soiled straw from the box, Horst stacked fresh straw on top of soiled, allowing the lower levels to generate heat as the composted, and reducing the space from floor to ceiling.

In the long days of summer, each hen gives him an egg a day; in the winter, very few.

The hens love to tear into the compost pile and dig at squash and pumpkin roots. They destroyed a cuke mound, some corn, and perhaps most unforgivably, developed a taste for tomatoes. So, this time of year when the vines are heavy with tomatoes, he only lets them out of the coops for the last half hour of the day and keeps a lookout for unsavory behavior. At dark, they return to the coop.

Three fast-growing Pekin ducks waddle and kvetch, drinking from a kiddie-pool, the dirty water from which he uses on some plants. As ducklings they were confined, but he’s “finishing them off” by letting them range the yard, figuring they will taste better.

In the coming weeks, he plans to assist a friend who has a poultry processing operation, with the slaughter of ducks and perhaps the chickens. “I think I should [do that] if I eat them. A lot of people are really disconnected from their food.”

***

Horst shows off his new honey bee hive.

This summer, after asking neighbors if they were allergic to bee stings, he installed honey bees in a top-bar hive, a horizontal trough in which combs hang from removable bars. The bees have multiplied by the thousands. He’s gotten three stings he figures he deserved, and has joined Maumee Valley Bee Keepers Association.

Bees swarm around flowers.

“My bee smoker is my great-grandfather’s, more than 50 years old. He’s the Mike I was named after. I did not know he was a beekeeper before I told my grandpa about getting bees and he suggested I inherit the old gear.”

In the fall he expands the garden, not by digging up turf but via the lasagna method: layering cardboard, grass clippings, and leaves on new-garden areas. The following spring, he’ll dig a hole through the layers and install the plants.

“I try to grow more than the pests can eat. I’m going for an 85-percent success rate,” he says. “It’s all a learning experience.”

Michael Horst, replacement sales at Overcashier & Horst, living in West Toledo.

Garden dimensions:

Six to eight plots totaling maybe 2,000 square feet.

When did you start gardening?

On purpose? I was a 12 year old and my parents said if I wanted my own garden, I’d have to take care of it myself, so I grew the vegetables I liked to eat. In school you grow the bean plant: it’s always been fascinating.

Before that, home videos show me diapered, playing among the tomatoes and garden mud. My father grew up on a farm and his father raised grain and beef cattle. My grandmother, Jo Ann Dixon, is a master gardener.

What do you grow?

The soil is mostly clay so I’ve had to work at it.

The fruit includes honey crisp and granny smith apple trees, Moorpark apricot, red haven and elberta peaches, plum, a bing and a black tartarian cherry tree. A few blackberry, blueberry, raspberry, and red currant plants, hardy kiwi, pineberry ( a white strawberry with the flavor of pineapple), and arctic strawberries.

Artichoke plants, asparagus, arugula, six kinds of beans, beets, broccoli, brussel sprouts, buckwheat (for ground cover), cabbage, Russian red kale (it overwintered with a sheet of heavy plastic over it), six types of carrots, cukes, Golden Bantam corn (a small variety), dill, eggplant, echinacea, fennel, garlic, giant pumpkins, ground cherries, horseradish, Iroquois melon (a muskmelon), amaranth.

Also, hairy mountain mint, catnip, butterfly milkweed, cup plant, 25+ varieties of heirloom tomatoes, lettuces, kales, radishes, fingerling potatoes, sweet potatoes, squash, turnips, onions, sunflowers, peas, kohlrabi, spinach, and I’m sure I’m forgetting some.

Flowers include button bush and New England aster. A carnivorous pitcher plant, its deep, narrow vessels holding liquid, serves as a bug trap.

A variety of tomatoes from Horstâs garden.

Favorite plant?

Chickens penned in the backyard.

Sunflower for its ability to rise above. Giant pumpkin for the ability to overtake its challenges. The giant pumpkin I grew last year weighed about 300 pounds. I rolled it on a tarp and hauled it out front. I ate a lot of its seeds and the chickens did too.

Give us a tip:

Mulch! Even if it’s just clean cardboard and grass clippings/leaf matter. And when I transplant, I fill the hole with SweetPeet, It’s very rich and gives the plant a good start.

Hours spent gardening per week?

One to five.

Annual expense:

$250, not counting chicken and duck feed.

Challenges:

Japanese beetles (aka chicken snacks), guiding prolific growth (ever stake a 20-foot-long tomato vine?), sharing/preserving the surplus (too many eggs!).

Unfortunately the squirrels got the three sisters (corn, beans, and squash planted symbiotically in a mound as Native Americans did). Squirrels also got the corn.

Of two artichoke plants I bought in four-inch pots, one has two fruits. I’ll cover up the other with mulch and it should bear fruit next year

I’m proud of:

Having an urban farm despite a full and busy life, especially the honey bees, ducks, chickens, bunny, and dog. I’m also proud to share any inspiration I can whether it be books, experience, seeds, or surplus.

*

What do you get out of gardening:

Gardening grounds me. It’s the practice of accepting the things I can’t change and changing the things I cannot accept. Plus, it makes me seem like a better cook. And it’s a great return on investment: You can plant a single clove of garlic and you might get a six-clove head. And if I save money on produce, I can spend money on better quality grass-fed meat

Contact Tahree Lane at: tlane@theblade.com or 419-724-6075.