COMMENTARY

Retire? No way; at 90, storied Detroit judge still learning

7/25/2014

Lessenberry

The Blade

Buy This Image

Lessenberry

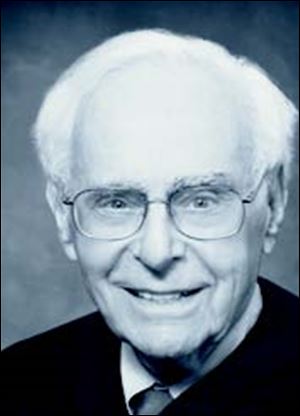

DETROIT — Nearly everyone in Michigan’s legal community knows U.S. District Judge Avern Cohn. He is one of the most colorful, fascinating, and occasionally temperamental justices on the federal bench. He is brilliant and hard-working. He turned 90 last week.

What are his plans for retirement? “They’ll have to carry me out,” Judge Cohn chuckled. “I’m happy. Every day is different. You are always learning something new. This is a job that keeps you young.”

That certainly seems to have been true for him. These days, the judge — who for years was a world traveler who scampered among Mayan ruins — uses a cane.

But nobody, even those lawyers who have been scorched by his occasionally acidic tongue, thinks he has slipped a step mentally.

Next week, he passes another milestone. Not only will he be the oldest federal judge in Detroit, he will become the longest serving, when Julian Abele Cook — a mere lad of 84 — fully retires.

Judge Cohn is not, however, the oldest federal judge in the country. More than a dozen others are older. Most older jurists, however, take senior status and work only part time. Judge Cohn took senior status in 1999, but has never reduced his caseload.

Cohn

By his count, he has weighed in on nearly 10,000 cases — not all of which went to trial — since he took the bench in 1979. Judge Cohn has had his share of high-profile cases, from a landmark windshield-wiper patent case to former Detroit City Council member Monica Conyers’ corruption trial.

A staunch defender of the First Amendment, Judge Cohn made national headlines in 1989 when he struck down the University of Michigan’s anti-hate speech code. Six years later, he threw out charges against a U of M student who posted Internet fantasies about raping and killing women, saying that while his words were repulsive, they were constitutionally protected free speech.

When I asked whether he had a favorite case, he told me: “Not really.” He paused. “You know,” he said, “a judge who wants a case should never have it.” For him, it’s the luck of the draw.

That, he says, is how he got to the federal bench in the first place. “You can’t count on being a judge,” he said. “It’s 20 percent skill set and 80 percent just plain luck.”

More than half a century ago, he very nearly was appointed Michigan’s attorney general. The incumbent had resigned, and then-Gov. John Swainson went through a complex process of vetting dozens of candidates.

In the end, the choice came down to Mr. Cohn, then a fast-rising Detroit attorney, and Frank Kelley, who was practicing law in Alpena. Mr. Kelley, who had also lived most of his life in Detroit, got the nod, largely because he was seen as being from outstate.

The runner-up was briefly angry, but today has no regrets. Judge Cohn said: “[Mr. Kelley] got the job he should have had, and I eventually got the job I should have had.”

For nearly two decades before he went on the bench, Mr. Cohn carried on a lucrative business law practice. He volunteered for the American Civil Liberties Union and in a host of civil rights causes. He became a major force in Jewish philanthropy in metropolitan Detroit.

In 1979, President Jimmy Carter nominated him for a new seat on U.S. District Court in Detroit. Mr. Cohn was confirmed easily.

Republicans held the White House for most of his years on the bench, which meant there was little chance of his being appointed to the federal appeals court. But he says he doesn’t regret that a bit.

“God, no,” Judge Cohn said. As as appellate judge, he said, “you never get to see anybody. All they do is review masses of paper.”

A lifelong Democrat, Mr. Cohn said his role model as a judge was a Republican: The legendary John Feikens, a former state GOP chairman who was his senior colleague on the bench.

“He had his shortcomings; I assume I have mine,” Judge Cohn said. “But he was my model in how he comported himself.” They remained close until Judge Feikens died three years ago at age 93.

Judge Cohn has no plans to die or retire. “Have you seen my chambers?” he asked, referring to the palatial space provided to a federal judge. “I would miss it.”

Odds are, the legal system would miss him too.

Jack Lessenberry, a member of the journalism faculty at Wayne State University in Detroit and The Blade’s ombudsman, writes on issues and people in Michigan.

Contact him at: omblade@aol.com