COMMENTARY

Future of U.S. may depend upon making citizens media literate

10/26/2017

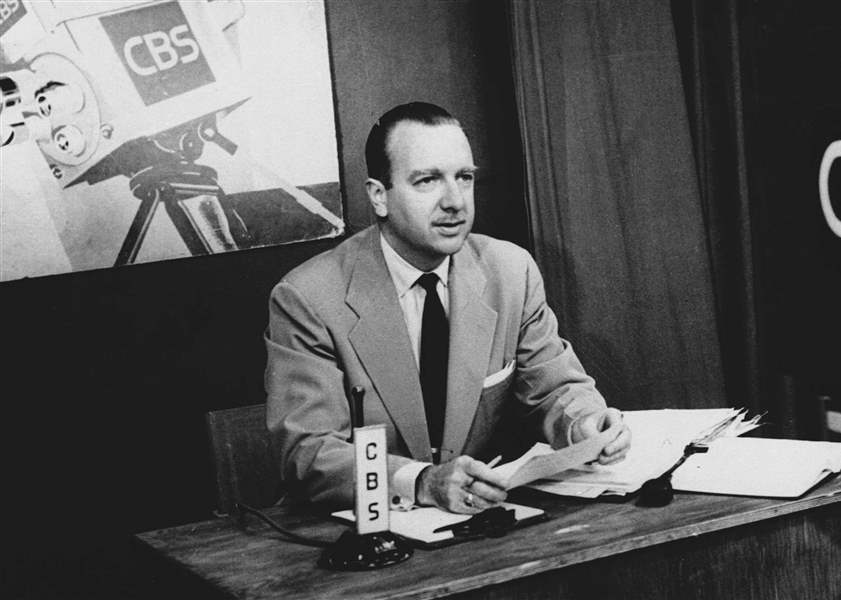

With today's overload of left-leaning and right-leaning sources delivering their own facts, the days when most Americans trusted broadcasters as much as they did Walter Cronkite are gone.

ASSOCIATED PRESS

LANSING — This may be a world in which good journalism is needed more than ever — but these aren’t great times to be trying to make a living in journalism.

Newspapers have been losing ads to the Internet and losing readers who think they can get all the news they need online, on the glowing screens of their smart phones.

Worse, they’ve been losing credibility with the public in a way never seen in modern times. A professional Morning Consult poll conducted for POLITICO revealed that 46 percent of Americans think the news media invent false stories about President Trump.

With today's overload of left-leaning and right-leaning sources delivering their own facts, the days when most Americans trusted broadcasters as much as they did Walter Cronkite are gone.

In fact, no respectable newspaper or network ever does that (though whether they report everything with an unbiased tone is more debatable.) Having spent my life in this business, working in every medium, I can honestly say that deliberately publishing false information doesn’t happen.

True, the profession gets journalism’s occasional equivalent of a suicide bomber, like Jayson Blair in 2003 or Toledo native Janet Cooke in 1981, who makes up false stories.

Neither of them, however, did so for political reasons; both had their careers destroyed, and in the case of the New York Times, the executive editor and managing editor were also fired.

Rather than make stories up, most outlets bend over backwards to make sure what they report is credible. For example: Last June, CNN published on its website — but did not air — a story saying a top Trump adviser’s ties to a Russian investment fund were being investigated by the U.S. Senate.

However, they did not have conclusive proof — and within days, CNN not only apologized, they fired three journalists involved.

Earlier this year, the leadership of another profession under siege — the state’s librarians — asked me to try to explain the fake news phenomenon and offer some advice.

Leanne Sandoval, director of professional development for the Michigan Library Association, asked me to talk to the state librarians’ annual conference. “Fact-based journalism has taken a back seat to fake news in some cases,” she said.

“Please tell us what is the difference, how the news media is responding, and what should libraries be doing to mitigate the impact of fake news,” she asked.

What I told Michigan’s librarians was this: First, trained reference librarians are needed more than ever, to help people make sense of the cyberspace world we live in.

How we got to this situation where the public so massively misunderstands what responsible journalists do is baffling — until you consider how the media world has changed.

Lessenberry

Perhaps the biggest reason is that Americans no longer all watch, read, or listen to the same media — and no longer have the same “intellectual furniture.”

For a moment, travel in time back to 1980. The vast majority of Americans then got their news from three places: a daily newspaper put out by professional journalists; a local, half-hour TV newscast from a station affiliated with one of the major networks; and a national nightly news broadcast produced by a major network.

Those news “products” had their faults; mainly, those deciding what to put in them were overwhelmingly white men in late middle age.

But they gave the public a coherent shared picture of reality. When Walter Cronkite said “and that’s the way it is,” most viewers accepted that was the way it was.

The abandonment of the Fairness Doctrine in 1987 meant broadcast stations no longer had to present balanced views. The Telecommunications Act of 1996 dropped most restrictions on how many broadcast stations one company could own.

Before long, right-leaning voters had their own broadcast news; left-leaning voters theirs, and millions of Americans lived in completely separate worlds.

On top of that, the invention of the World Wide Web in 1989 meant that a decade later, a huge majority of Americans could surf the Internet in their homes — without a field guide.

For a trained journalist, the difference between a credible news site and a dubious one is often obvious. Reporters and editors usually know how to identify fake news.

However, there is no reason the average person should be expected to do so.

But I do know this: We desperately need courses in media literacy in high school, college, and for the general public.

Librarians, teachers, and yes, trained journalists, need to collaborate and figure out how to offer them.

This means training everyone how to easily distinguish between self-evident truth, clear lies, and those many things honestly open for debate.

Americans may differ politically, but decent liberals and conservatives alike have a common interest in teaching everyone that the mainstream media do not deliberately lie.

That common interest is in the survival of democracy, honesty, and possibly the United States. Most of the librarians seemed to agree. I hope you do too.

Jack Lessenberry, the head of the journalism faculty at Wayne State University in Detroit and The Blade’s ombudsman, writes on issues and people in Michigan. Contact him at: omblade@aol.com.