Trayvon Martin shatters myth of postracial America

Reaction reflects past, points to future challenges

7/21/2013

Protesters staged a sit-in outside Florida Gov. Rick Scott’s office on Tuesday in response to the not guilty verdict in the trial of George Zimmerman, the Florida neighborhood watch volunteer who fatally shot Trayvon Martin.

ASSOCIATED PRESS

Protesters staged a sit-in outside Florida Gov. Rick Scott’s office on Tuesday in response to the not guilty verdict in the trial of George Zimmerman, the Florida neighborhood watch volunteer who fatally shot Trayvon Martin.

Trayvon Martin’s senseless death has become another milestone. It will inform this nation’s debate on race for a long time, as did the videotaped beating of Rodney King by Los Angeles police officers in 1991 and the acquittal of O.J. Simpson in 1995.

Martin

No one can reasonably deny racial, or class, biases in the criminal justice system — even George Zimmerman’s lawyer, Mark O’Mara, acknowledged them. We know that Trayvon Martin, a 17-year-old African-American wearing a hoodie, was singled out because of his appearance. We know that neighborhood watch volunteer George Zimmerman could have — and should have — avoided this lethal encounter.

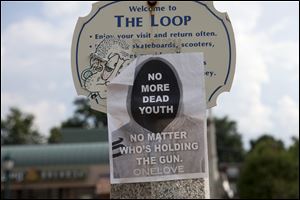

A flyer about the Trayvon Martin case is posted on a light pole in University City, Mo.

That said, I won’t waste time second-guessing the jury’s verdict or debating whether the evidence met the legal standard for second-degree murder or manslaughter.

What is beyond a reasonable doubt, however, is that whites and African-Americans, in general, reacted far differently to the verdict, reflecting the nation’s past and illuminating the challenges ahead. Anyone who talked to both white and black people after the verdict knows this.

Last Sunday, I talked briefly with two close friends who are African-American and both about 40 years old. The verdict confirmed their belief that a young black man can’t get justice in America — at least not with any assurance.

“This dude [Zimmerman] got away with murder,” one friend told me. “Michael Vick got two and a half years for killing some dogs, and this guy profiled a young brother with a hoodie on in the rain and killed him.”

My other friend said he was disappointed but not surprised. “My only immediate comfort is in knowing that he’s probably the least free so-called free man in America. He’ll be scared to even walk out to a mailbox for the next six months. Hey, we gotta take our justice in America anyway we can get it, right?”

Most of white America, except possibly teens and young adults, reacted quite differently. Many believed the verdict was justified and just. For them, Trayvon Martin’s death was tragic but as much his fault as it was Zimmerman’s.

I heard one white person say that black people need to stop whining and start behaving. Another said African-Americans were needlessly injecting race into the verdict.

“It wasn’t a race thing,’’ he said. “Zimmerman was part Hispanic, anyway.”

It’s not surprising that many whites feel that way. Unlike African-Americans, white people don’t have to think continually about race. So they often do not understand why other people do.

White and black Americans agree on a lot of things — basic stuff such as the value of family and a good education. But on certain issues, black and white Americans part ways.

That’s not surprising either. Attitudes are shaped by experience and history. And the experience and history of white and black Americans in dealing with the criminal justice system have been far different.

Historically, the criminal justice system — police, courts, jails, prisons — has often been an instrument of oppression of black people. In the South, the legal system, through terror and coercion, kept African-Americans “in their place” during the Jim Crow era. With guns and fire hoses, it helped suppress the struggle for civil rights during the 1950s and 1960s.

The system also enforced some horrific miscarriages of justice. A few such cases, such as the trial of the Scottsboro Boys in 1931 and the murder and mutilation of Emmett Till in 1955, became internationally known.

In the Till case, a 14-year-old African-American boy was brutally murdered for allegedly flirting with a white woman. An all-white jury acquitted the white killers, who months later in a magazine interview admitted the killing.

Times may have changed, but complaints about police abuse and unjust courts continue. In the hood, most police aren’t known as “Officer Friendly.” They’re the guys who rousted you on the corner, beat down your brother, or didn’t show up for a 911 call.

Many police officers treat all people with respect and do their jobs well. But in high-crime areas with a heavy police presence, some people who are just minding their business are going to be profiled and treated unfairly.

They will resent it — so would you. The anger of many young black men in the hood toward the police has been graphically expressed in hip-hop and rap music.

The explosion in the nation’s prison population over the past 30 years has disproportionately affected black men. Some scholars and writers have dubbed incarceration the new Jim Crow.

Many young black prisoners I’ve talked with describe incarceration as the new plantation. Black men make up nearly 40 percent of the 2.3 million people locked up in this country.

Numerous studies, including a report by the American Civil Liberties Union last month, have shown that blacks are arrested at far higher rates than whites for drug possession, even though drug use among whites and blacks is about the same. The notorious 100-to-1 sentencing disparity, recently narrowed, between crack and powder cocaine is another example of unequal treatment.

According to supplemental homicide reports submitted to the FBI between 2005 and 2010, African-Americans are far less likely to be adjudicated as justified in using deadly force in a firearms-related death. The differences between rates of justifiable rulings in cases with a white shooter and a black victim, and cases with a black shooter and a white victim, are stark and striking, especially in states with “stand your ground” laws.

Racial profiling, though even more difficult to measure, is prevalent and a generally acknowledged problem in law enforcement. I suspect there are few black men in this country who haven’t been profiled at some time.

I’ve been pulled over in random traffic stops only three times. On each of those occasions, I was riding with at least one African-American. During one stop, the state trooper started the conversation by asking if either one of us was on probation. It’s not an unusual question if you’re Riding While Black.

So it’s not surprising that African-Americans and whites reacted differently to Trayvon Martin, and to Rodney King, and to O.J. Simpson. Whites were horrified when a few African-Americans openly rejoiced over O.J.’s acquittal. I suspect the celebrations had a lot less to do with any love for O.J., who has done nothing for his community, or even a belief in his innocence, as much as it did with a visceral feeling that, hey, for once, we turned the tables on you.

Trayvon Martin rallies continue across the country. Contrary to the predictions of some media fearmongers, however, the events were largely peaceful.

I disagreed too with the verdict. But as a former juror, I know the jury didn’t come to the decision lightly.

People can too quickly label someone a racist and shut down further communication. Supporting the Zimmerman verdict doesn’t make someone a racist or a fool.

But even those who support it should understand why people whose history and experience are imbued with racism could view the verdict as insidious, another example of America’s racist history. Without some real talk on justice and race, we’ll continue to look at one another in astonishment, anger, and fear.

The needless death of Trayvon Martin has shattered the myth of a post-racial America with a verdict that has, once again, defined our differences. This time, let’s at least try to understand them.

Jeff Gerritt is deputy editorial page editor of The Blade.

Contact him at: jgerritt@theblade.com, 419-724-6467, or on Twitter @jeffgerritt.