Commentary

Pass the mic to Toledo’s youth

With a middle-aged white guy lecturing an audience that resembled an AARP convention, something was missing from this forum on diversity

10/6/2013

Among Toledo youths at a meeting at the Soul City boxing gym are, from left, Daveon Foster, 12; Alexis Smith, 17; Rhonda Paris, 19; Major Smith, 18; Caleb Jones 10; and Trevonn Smith, 14.

HANDOUT NOT BLADE PHOTO

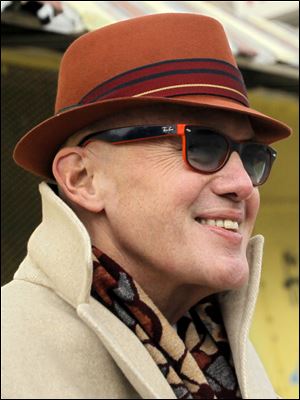

Jeff Gerritt.

On the grind in my office until 10:30 p.m., I missed the community forum on racism a few weeks ago. I’m sure speaker Tim Wise, who wrote White Like Me, delivered a straight-on message.

But a middle-aged white guy lecturing an audience that resembled an AARP convention left me wondering whether something was missing in this conversation on diversity.

Young people are usually MIA whenever Toledo’s shot-callers talk turkey. That’s unfortunate for a community looking for real talk and practical solutions.

Youth represent the future. They’re on the front lines of many of the issues Toledo cares about; education, music and the arts, public safety, drugs, poverty, vocational training, economic development, recreation, gangs. Young people live the issues others talk about, including the school-to-prison pipeline that has swallowed too many young black men.

Among Toledo youths at a meeting at the Soul City boxing gym are, from left, Daveon Foster, 12; Alexis Smith, 17; Rhonda Paris, 19; Major Smith, 18; Caleb Jones 10; and Trevonn Smith, 14.

To hear what they had to say about race in Toledo, I asked Alicia Smith, program coordinator for Maturing Young Men, to gather a half-dozen young people at Soul City on Junction Avenue. Owned by mentor and coach Roshawn Jones, 24, the building, which includes a boxing gym and barber and beauty shop, has become a refuge for dozens of central-city kids.

“You’ve got to keep these kids in some kind of program — give them some structure that they might not have at home — because they face a lot,” Mr. Jones told me. “Unfortunately, no one wants to invest in inner-city kids or the organizations that help them.

“No one really cares about young African-Americans killing each other,” he said. “This is a place where inner-city kids can spend their time well, but the media don’t want to hear about that.”

Mr. Jones plans to start a program called Choices, where adults talk to kids about anger management, substance abuse, and other issues.

One of his young athletes, Daveon Foster, 12, described dodging bullets near his home two years ago. Caught in a gang-related crossfire, he was lucky to survive. With older brothers already involved in gangs, Daveon boxes to stay focused.

“A lot of these kids come from broken homes, but they can still make something of themselves,” said Alexis Smith, 17, a senior at Toledo Technology Academy who plans to study biomedical engineering. “It’s important to instill the value that we are kings and queens.

“The whole fight against racism isn’t about convincing people that racism is bad,” she said. “It’s more about taking away the power of racism by showing kids that they are important.”

Alexis is working on a media project called Good News Network — young people broadcasting inspiring stories about other young people.

Her brother, Major Smith, 18, who is studying film, said the media, including music, spew too much negativity. Except for Wale, he said, few rappers today try to educate, as Tupac Shakur and Biggie Smalls did in the 1990s.

Already in his second year of college, Major often feels isolated from his peers. “I meet a lot of guys my age who aren’t doing very well,” he said. “Deep down, it hurts. I try to talk to them. Maybe they’ll feel like they have to step up their game, because they [society] want us to fail, for real.”

Major wants to reach young people through film, portraying uplifting and instructive images of contemporary African-Americans, especially men.

Racism is something these young people all have experienced, but won’t let define or stop them.

Trevonn Smith, 14, a sophomore at Whitmer High School who wants to become an aerospace engineer, told me that several white classmates jokingly pretended to point a gun at him, after another young African-American with a similar first name, Trayvon Martin, was shot and killed by George Zimmerman, who was acquitted in July.

“I wanted to fight, but I just ignored it,” he said. “When I want to let [my emotions] out, I just write how I feel.

“My mom [Katrina Smith] gets on me about being a strong positive black man who does something for his community. I want to be that strong black man that kids look up to.”

I’ve had many similar conversations with young people in Detroit and other cities — and, too often, in prisons and juvenile jails. Often, their lives intersect with violence, poverty, crime, and drugs.

It’s harder than most people know to go another route on blocks where the margin for error — the line between success and failure, even life and death — is razor-thin. It should not surprise us that a few of these kids fail, but it should amaze and inspire us that many of them succeed.

The young people I talked to at Soul City feel a lack of support from their government and community. The idea that “they” — society at large — want them to fall, or even kill each other, runs deep among young African-Americans in poor neighborhoods. Almost everything they encounter, including their schools and the streets they walk, confirms it.

On the issue of racism, they’re less interested in how white people think than they are about defining themselves. Above all, they aren’t looking for someone to speak for them.

“I’m a little fed up with that idea,” Alexis told me. “I need to speak for myself, because I’m very capable of doing that.”

But they are looking for a microphone, a seat at the table, where they can help shape their, and their city’s, future.

If we’re smart, we’ll give them one, shut up, and listen.

Jeff Gerritt is deputy editorial page editor of The Blade.

Contact him at: jgerritt@theblade.com, 419-724-6467, or follow him on Twitter @jeffgerritt.