Gangs in Toledo: Where do we go from here?

5/5/2013

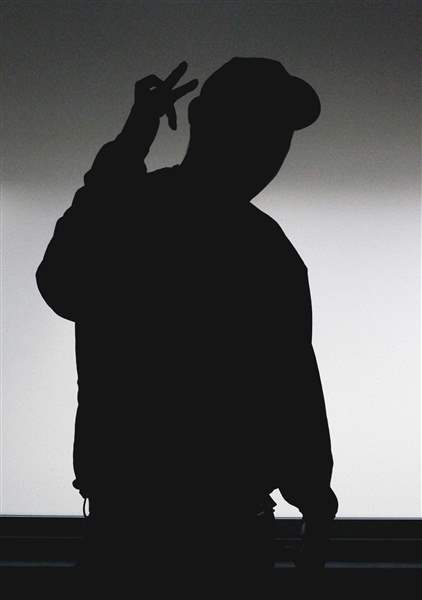

SLUG: CTY gangd2 Date: 3/8/2013 Toledo Blade/ Amy E. Voigt Toledo, Ohio CAPTION: A member of the hispanic gang "Vato", who did not want to be identified, flashes a gang sign at his home in Toledo on March 8, 2013.

THE BLADE/AMY E. VOIGT

Buy This Image

Gangs have left a mark on Toledo, from graffiti scrawled on houses, to people such as Mitchell Moore, top left, who lost a son to a shooting, and the Lawrence Blood Villains, bottom left, who recently remembered a fallen member. Meanwhile, city police confront a growing problem.

Toledoans are talking, and thinking, about The Blade’s gang series — Battle lines: Gangs of Toledo. It’s a stunning accomplishment. The sheer amount of work — writing, filming, and legwork — done by Taylor Dungjen and Amy E. Voigt, as well as by the Blade’s newsroom editors and art staff knocks me out. What a commitment — to serious journalism and to the community.

Then there is the empathy in the writing. No judgment, just good storytelling. Miss Dungjen helps us to see that, even while living rough, mean lives, human beings try to make the best choices they can and be loyal to those they owe and those they love.

I think also about the physical bravery of those two young women. I have a daughter roughly Miss Dungjen’s age who is also very brave.

At a time when most newspapers are pulling back from the big investigative story and divesting in community journalism, this newspaper told a vitally important story, and told the truth, without fear or favor.

The question is: What now? What do we talk about now; how do we have that conversation; and what action should be taken?

It’s obvious that the first thing we need to talk about are the gangs themselves. They are devouring the lives of young people in this city and wrecking many of the lives they do not take. And the gangs are so widespread and pervasive — the power of the map — that virtually no neighborhood is untouched.

I don’t believe in simple one-note “answers” to social questions. But I believe there is an approach to gangs out there that is practical, compelling, and could make a difference in Toledo. It is called the “Ceasefire” strategy, and it is the brainchild of David Kennedy, formerly of the Kennedy School of Government at Harvard and now of the John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York City. Mr. Kennedy is not a criminologist by training, indeed he is not an academic at all, but a writer and seeker of justice in the urban jungle. He started Ceasefire in Boston and has successfully transposed it to several other American cities.

SLUG: CTY gangd2 Date: 3/8/2013 Toledo Blade/ Amy E. Voigt Toledo, Ohio CAPTION: A member of the hispanic gang "Vato", who did not want to be identified, flashes a gang sign at his home in Toledo on March 8, 2013.

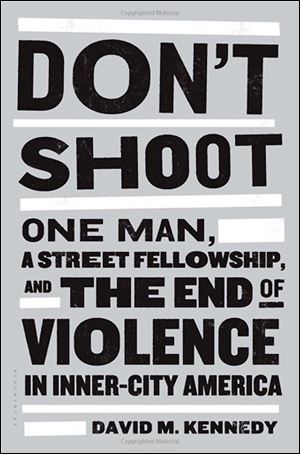

Mr. Kennedy outlines the history of the movement and its successes and failures in a new book titled Don't Shoot: One Man, a Street Fellowship, and the End of Violence in Inner City America.

Here is how Ceasefire works:

First, the police force focuses on one thing: Guns. It does not try to eliminate gangs, or the drug trade, or the underlying causes of gangs, like fatherlessness or poverty. The police focus solely on gun violence, and specifically the people who commit gun violence. And only on this. (This approach is controversial. Mr. Kennedy does not say churches, for example, should not focus on poverty or dads, but that dealing with gangs is first a police problem and fundamentally a gun problem. Gangs without guns don’t concern him greatly and neither does drug use particularly concern him. His goal is to stop the shooting. )

Second, Mr. Kennedy’s premise is that the people who are responsible for this violence are a small number of people and are mostly well known to the police. He says the police must leverage this.

Third, the police and prosecutors must focus very intently on these few people. In the Ceasefire program they are all called in, confronted, and warned that they are being monitored, that gun violence will no longer be tolerated, and that the smallest false move — a traffic violation, even a parking ticket — will result in even more personal attention and in maximum available legal punishment.

The Ceasefire approach is personal — intensely personal. In some cases the police bring in gang shooters to meet face to face with the mothers and girlfriends of people they have killed. This was done in Hartford recently, where the program is just beginning.

Mr. Kennedy’s approach has gotten results. In cities ranging in size from Boston to Winston-Salem, N.C., gang shootings have been cut in half. (When Boston abandoned the approach, gang shooting rose again and Boston has gone back to it.) Mr. Kennedy’s success in Boston in the 1990s was called, by many, a “miracle.” Mr. Kennedy hates the word. He says it was simple hard work based on pragmatism, street sense, and ability to learn from real life successes and failures.

Imagine this reaction to The Blade’s gang series: a round of public forums — lectures, panel discussions, seminars, Town Halls — with maximum public participation, on the future of Toledo. Topics might include housing, street repair, domestic violence, schools. But start with gangs.

And make David Kennedy the first speaker. While he’s here he could consult with the Toledo Police Department. Mr. Kennedy usually starts with a given city police force knowing full well that they doubt he is for real. He tells them, “Give me one hour.”

There are other things to be said about gangs and the city and other issues to grapple with. Former Mayor Jack Ford says that some years ago, while teaching at Bowling Green, he and some graduate students working with him put together a report on the availability and efficacy of Toledo youth support services. What they found is that there are many programs for youth in the city and a fair chunk of money is spent for this purpose (90 organizations when they did the study in 2007). But they don’t talk to each other. He advocates “a countywide system of case management and collaboration between all youth service agencies.”

David M. Kennedy outlines the history of the ‘Ceasefire’ movement in Don't Shoot.' It's an approach to gangs that is practical, compelling, and could make a difference in Toledo.

Suppose Toledo’s diffuse collection of youth programs became a system. Suppose a youngster entered a county system with a case number and remained in the system, being guided to the right programs at the right times in his life. Suppose he had a case worker, or advocate, who had his back and was making sure all the different programs were communicating with him, his family, and each other.

No, life is never quite that neat and social services can’t be either, but we could at least better use the resources we have to present street kids with a real sense that they have an alternative, a choice.

Carty Finkbeiner, another ex-mayor, still quite active in town, also sees communication as a key problem in the city. The public feels disconnected from city government and services. The sense, he says, is that “nobody’s listening.” Interestingly, Miss Dungjen and Ms. Voigt felt they got much of the good copy and video they captured from gang members because these individuals felt someone was listening to them for the first time in their lives. A similar theme is heard in a great book on gangs, Tattoos on the Heart, by Gregory Boyle, a Jesuit priest who works with the worst of the worst gangs in L.A.

So, no easy answers came out of this series, but awareness and engagement have already come and direct engagement — by the police with gangs, by social services with each other, by citizens with each other — may be the ballgame. Not just a beginning but the way forward.

Keith C. Burris is associate editor of The Blade.

Contact him at: kburris@theblade.com or 419-724-6266.