Abandonment, hope, and a man who hangs in

5/19/2013

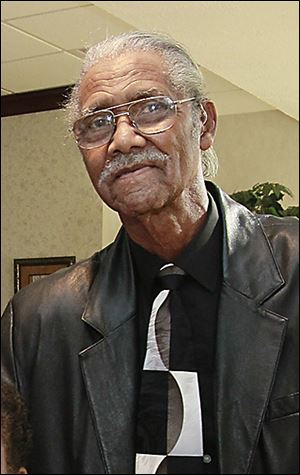

Ford

THE BLADE/DAVE ZAPOTOSKY

Buy This Image

Ford

A few days ago, I spent a couple of hours riding around blighted Toledo with ex-Mayor Jack Ford and his friend Weldon Douthitt, who was celebrating his 80th birthday. We were surveying the city’s housing stock — some of its many abandoned homes and forgotten neighborhoods.

Mr. Ford, who is running again for Toledo City Council, is deeply concerned about this city’s housing situation, which he says is the worst he has seen in 30 years. He said he’d made a similar tour about four months ago, and things have deteriorated since then.

We drove first by the Greenbelt Apartments where, nearby, a baby named Yealaysia Williams had been hit by a bullet fragment the night before. She survived.

Then to Moody Manor where, one year ago, another child, Keondra Hooks, caught a stray bullet from 12 rounds shot into her apartment. She did not survive. Mr. Ford said few adult men live there. The city is uninvolved at Moody Manor because the Catholic Diocese of Toledo owns the property and a private contractor manages it. But no one seems to be in charge.

And then we began our tour of street after street of abandoned and stripped houses. We didn’t go east or far south, but we went to the Warren Sherman neighborhood and the north end near Sherman Elementary school.

People are walking away from their houses in droves all over the city, and then the looters descend — stripping the homes of brass fixtures, plumbing, lighting, the windows, and eventually the siding.

In time, the boards go up. And the weeds grow. And finally, when the foundation starts to sag because of complete exposure to the elements, the city tags the house for demolition.

Douthitt

The city, working with the Lucas County Land Bank, has targeted more than 800 homes for destruction. It has a kitty of $6.9 million — some of which comes from the U.S. attorney general’s settlement with unscrupulous mortgage lenders — to do this.

But homeowners who are still trying to make a go of it in challenged neighborhoods remain, and they have to listen to the vandals rampaging at night and plundering nearby homes.

Many of these people have children. We drove by two brand-new elementary schools and the Ella P. Stewart Academy for Girls. None of them can be reached without schoolchildren having to walk though some very dicey areas.

Incidentally, many of these homes are rather new and decently built. They are abandoned nonetheless. We must have seen 50 empty homes that had been built within the past 10 years.

We saw so much devastation. “Why,” I asked. “What’s the cause?”

“An overlap of problems,” Mr. Ford said. “Poverty, gangs, drugs, domestic violence.”

“I’m just coming off the school board,” Mr. Ford added, “and I believe the low test scores, in addition to reflecting the convergence of race and poverty, reflect the housing crisis. How much hope can you have if you live in a dangerous, hopeless place? How much faith in your future?”

The car stops in front of a home with a porch and a small yard between the porch and the street, as well as a fenced back yard. There are three similar homes on the street, each with privacy, dignity, and individual character. This is what Jane Jacobs [the great celebrant and theorist of urban diversity] was writing about in her books, Mr. Ford says: individuality and variety; organic community.

But on the same street are six or seven ravaged — and savaged — homes.

So, almost $7 million for demolition. How much for rehabbing homes? There are some funds available for individual grants. But there is no broad program.

Can none of those 800 be saved?

A boarded-up home on Indiana Ave., with Family House at 669 Indiana Ave. in the background at far left. Family House had been in danger of losing funds and shutting down.

Admittedly, many homes should come down. They are too far gone.

The city has lost 100,000 people in the last 50 years. So it can’t sustain as much housing stock as it once did. And the Land Bank does what it can for individuals who want to buy cheap and reclaim an abandoned house. But surely there should also be a real program to support homeowners and sustain neighborhoods.

Mr. Ford says we do little to help the family that wants to be responsible. We don’t teach the skills of homeownership or assist the people who may already have a few of those skills.

Ironically, the city has a growing homeless problem, including homeless families. And now most of the shelters are facing drastic cutbacks by the federal government and the threat of more cuts from the city. (Last week City Council restored funding to three shelters — Aurora House, St. Paul’s Community Center, and Family House — that faced drastic reductions in funding. Family House, a shelter for families on Indiana Avenue, was confronted with the prospect of shutting down its toddler and school-age program this summer.)

Mr. Douthitt, an old construction man who trained out-of-work young black men and a few ex-offenders in construction in the 1970s, says you have to catch an abandoned home at its tipping point — just before the structure is compromised.

The current policy of the city is essentially the opposite: Wait until the home has had it, and then tear it down. What happens then? Not open spaces and urban gardens, but mostly, piles of rock and debris that remain in perpetuity.

“What if,” says Mr. Ford, “we filled an old warehouse with fixtures, brick, and usable wood from some of these homes we take down? Who gets the salvage rights now? Who gets the fixtures and bricks? And what if we had tools to loan there?”

Instead of looting and piles of rubble, how about a sweat-equity program for those remaining to fix up their homes?

And what if, asks Mr. Douthitt, we trained ex-offenders in construction rather than sending them back to prisons? Try helping a felon find a job in this economy?

What if the city spent some of its money building and rehabbing rather than leveling?

City government seems to be AWOL on housing policy and planning. Housing policy is in a state of abandonment, just as surely as those scores of houses are. I wonder where the mayor and City Council members are. Is this — abandonment and demolition — the best we can do?

I wonder if the police can find a practical way to be more visible. These neighborhoods need their constant presence. And we need more enforcement against stripping and selling siding and copper to reclamation centers. Surely the police know the identities of many of the scrap sellers and buyers. If the department needs more officers, let’s get them more.

I wonder what makes Jack Ford run. He is one of the most interesting minds I have met, maybe the most interesting, in my three decades in this trade. Mr. Ford is a public-policy intellectual and a man of many interests. But he is also a man of the streets. Everyone knows him in these neighborhoods and many call out to him: “Hey, Mr. Ford.” “Hi, sweetie” or “Hey, man” he calls back.

Mr. Ford is of retirement age and he has been through a harrowing health ordeal. He has been in high office and held power and known its limits. But he is still looking for a little justice; still looking to make life better for those who don’t have much in this world; still hoping, serving, hanging in.

Jack Ford still has a lot to give. But he can’t do it alone. Toledo needs a critical mass of new people who give a damn and will walk the walk — together.

Keith C. Burris is associate editor of The Blade. Contact him at: kburris@theblade.com or 419-724-6266.