COMMENTARY

Vigilance and brotherhood in Fire House 7

5/25/2014

The first thing a firefighter told me about his life and work — they are the same thing — is that he doesn’t sleep.

“Firefighters don’t sleep,” he said. “We just don’t. We’ve seen a lot of.... It works on your head.”

There are the runs. A firefighter’s shift is 24 hours. One full day on and two off. But he or she is on call all of those 24 hours. When duty calls — a car wreck, a suicide attempt, a fire — he goes. It’s not optional. And he can’t be simply present. He must be “all in” the whole shift. There may be five runs in a day. There also may be five in a night. There might be 18 in a 24-hour period — say on New Year’s Eve or July 4. Every year those are predictably wild days. But no other days are predictable. Except that, when the bell rings, you go. Fully prepared. Mentally ready. And that means that you cat nap in the down times and at night. You really can’t afford to go into a deep sleep.

A 24-hour shift means you have to be ready to give 100 percent physically, emotionally, mentally, when you are called upon.

Who else in our society works a 24-hour shift? Not doctors or nurses. Certainly not journalists.

On a night I spent at Fire House 7, we went on seven runs, between 5 p.m. and 7 a.m. And I was beat by morning, though I did nothing but ride. That was roughly half a shift.

Always on watch

Many firefighters say that after a day on duty, they toss and turn the night of the next day — the first day off. The second day off, they might sleep. But others told me they never sleep for more than an hour or two at a time. “You are always sort of listening, on watch. What was that? Did you hear that? So you can’t relax,” said one.

Another firefighter told me that the leading killer in his profession is heart failure. He said he thinks it’s partly because of stress and sleep deprivation. Still another said he thinks the biggest killer is booze.

So sleep is an issue.

So is food.

When I visited Fire House 7 in the Old West End (called “Sevens,” with a logo of a cowboy on the rigs) there was a lot of emphasis on meals. They fed me breakfast, and it wasn’t cold cereal. Lunch was solid and hot. One of the best cooks in the outfit was making his famous lasagna that night. Sadly, I missed it.

“Did you get enough to eat?” Lt. Ron Kay asked me. I said I did. “If you don’t get enough to eat here,” he said, “there is something wrong with you.”

A couple things strike me about that: A meal is what binds a family. The men at Sevens are family to each other. Toledo Fire and Rescue is the larger family. The community of firefighters throughout the world — a fraternity of honor — is the extended family.

Firefighter John Martin makes a Friday fish fry for the other members of Fire House 7 on 2155 Franklin St. Firefighter Mike Lester, left, jokes around at the kitchen table. But when the alarm rings, the meal is over.

‘Family’ time

Traditionally, most down time at the station is spent together, in the kitchen. Like any family.

And for some firefighters, the fraternity comes first — certainly before ex-wives or cousins.

The other things a kitchen and a meal represent are normalcy, stability.

There is nothing normal or stable about the life of firefighters. A third of that life is spent away from their real families. So they cling to custom, and folk ways, and the routines of a big, contentious second family.

These are, after all, people who run into fire, not away from it. They are not your average Joes or Marys. And theirs is not your average workday or workplace.

If you are just sitting down to a nice hot meal, as I was at Sevens and the bell rings, you leave that meal. “Ah, now you know,” they said to me as I dashed for the truck with a last gaze at my evening meal.

Members of the Toledo Fire Department, from left, Lt. Brian Henry, John Martin, Mike Lester, Barrett Dorner, and Ray Rodriguez socialize at Fire House 7. Most of their down time is spent around the kitchen table, just like any other family.

If you are finally starting to nod off and the bell rings for the fourth time since midnight, you can’t just roll over. You go. If you are a firefighter.

For me, the constant interruptions were discombobulating. They made me want, all the more, to get back to that food or sleep. How do you get used to it, I asked. How does your body adjust? You just do, they said. Your body never does. One firefighter told me he used to get an instant headache every time he heard the bell.

Yet firefighters also live for these interruptions. The variety. The challenge. No two days alike. Firefighters are the original adrenaline junkies. They are only truly disappointed when the interruption is for a sprained ankle or dizziness. And often it is.

If the call is for a car accident, an old woman who has fallen, or, especially, a fire, well, that’s the job. And putting out a fire — that’s the ultimate rush. “I can’t explain what that feels like,” one firefighter said to me.

Any problem solved or person helped is satisfying. The variety is interesting. But nothing compares to a fire. That is the ultimate challenge: Man against a natural element we know is stronger.

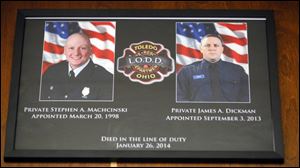

Station 7 personnel were some of the first on the scene of the blaze that killed Stephen Machcinski and James Dickman. These photos hang over the kitchen doorway.

More than fires

There are many things the public doesn’t understand about firefighters. Maybe most things. But the first is that they don’t just fight fires any more. They are medical first responders. All have EMT training, and about one in four are full-scale paramedics. Eventually, they will all be paramedics. All new recruits are required to commit to training to be full-fledged medics. And that’s necessary. Firefighters now treat injuries, wounds, heart attacks, and strokes on the spot. They have a machine called LUCAS, which is a portable defibrillator. “Rescue” is now 80 percent of what firefighters do. Fighting fires is only 20 percent of what they do.

And, for the poor of central city Toledo, Toledo Fire and Rescue are primary care givers. The urban poor do not have doctors, and they do not drive themselves to urgent care or the emergency room. They call 911.

Moreover, when you hear on the evening news that a rescue team used the Jaws of Life to pull someone out of a car wreck, that’s not a phantom rescue team. That’s Toledo Fire and Rescue — “firefighters” who are also medics, de facto emergency nurses, an ambulance service, and rescue divers. Oh, and they are also trained in HAZMAT.

These guys do not sit around the firehouse playing cards.

You know what they do when they are in the firehouse and not on runs? They watch videos of fire and try to learn from them. They do drills — crawling through small holes and over pipes. They practice intubating or injecting. They study the science of firefighting and the art of rescue.

In down time, they might also lift weights or clean the station. Firefighters have to stay fit. Unlike the NFL and NBA, you don’t quit at 35. You have to be in fighting trim at 45, even 55.

And, the station being their home away from home, they take care of it. Firefighters buy their own furniture, TVs, weights and exercise equipment, and, of course, food. The city does not provide any of that. The city does provide plastic mattresses, so in most stations, firefighters buy their own mattresses too.

A captain’s helmet and logo of Station 7 adorn a wall in the kitchen of the firehouse.

Strong bonds

On my first visits to Sevens, the fire in Boston that took the lives of two firefighters on March 26 had just occurred. So they were watching video of that. Partly this was as homage. Partly they wanted to learn from it. Some of the firefighters from this station went to Boston to pay their respects a few days later, just as firefighters from Boston came here for the Last Call memorial for Stephen Machcinski and James Dickman, killed at 528 Magnolia St. on Jan 26. Station 7 was one of the first to the scene of that fire. On that day, firefighters carried their fallen brothers out of the inferno that took their lives.

The Magnolia Street fire is not a thing of the past to Toledo firefighters. They relive and rethink it every day. Those two men were family. Firefighters use the word “family” and “brother” a lot. But not casually. These words are constantly invoked as renewals of their oath to each other. They actually elevate the words rather than cheapening them.

I have seen such bonds before — in classmates from small schools; in military men and women. My uncle went to West Point, and that bond, with classmates and fellow soldiers, was doubly tight. I have seen it among Catholic priests who were ordained and went to seminary together. And, even more, among monks who live, do physical labor, and pray together. But I have never seen a stronger bond than that shared by firefighters. Not only do they live together a third of their lives, but they risk their lives together. And, really, no one understands their life, or their bond, but them. You have to simply acknowledge and respect this. For firefighters, water is thicker than blood.

On Monday: The hidden city: Who and what firefighters confront on emergency runs.

Contact him at: kburris@theblade.com or 419-724-6266.