Augusta, Ga., is James Brown proud

Godfather of Soul’s memory is kept alive in boyhood town

2/23/2014

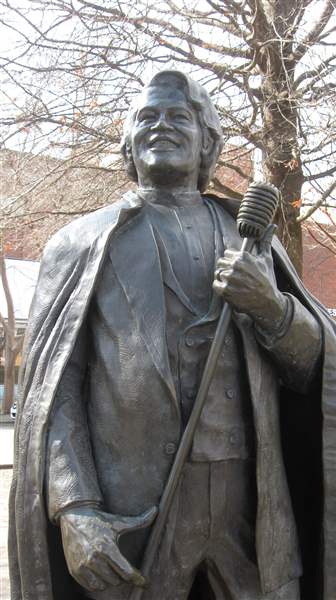

Visitors gather around the statue of James Brown on Broad Street and pose with it for photographs. The statue depicts him holding a microphone, his head held high with a wide smile on his face.

Mary Alice Powell.

AUGUSTA, Ga. — True, the Masters golf tournament is held here on hallowed ground every April.

But, golfing was the furthest thing from my mind when I spent a few days in Augusta this month.

I wanted to learn more about James Brown, the Godfather of Soul, and this is the place to go.

Augusta was Brown’s boyhood home and he never forgot it. He died on Christmas Day 2006 at age 73. Visitors to Augusta are reminded of the city’s claim to fame in several venues.

A major street downtown is James Brown Boulevard, and the largest building in the downtown entertainment complex is the James Brown Arena.

Visitors gather around the statue of James Brown on Broad Street and pose with it for photographs. The statue depicts him holding a microphone, his head held high with a wide smile on his face.

Visitors gather around the statue of James Brown on Broad Street and pose with it for photographs. The statue depicts him holding a microphone, his head held high with a wide smile on his face.

When I asked for directions to see the statue, I was told, “It’s not very big, but then he wasn’t a very tall man.”

But he was tall in good deeds and music innovation that helped pave the way for funk and hip-hop. Michael Jackson called James Brown his idol.

Brown did more on stage than cling to a microphone and bellow out songs he had written. He added lively dance steps and wore costumes that sparkled.

Brown grew up so poor that he was dismissed from school at one point for wearing insufficient clothing made from sacks. A collection of the costumes he wore as an entertainer is one example of the success he achieved.

The Augusta Museum of History devotes 2,000 square feet to Brown’s life and career. Executive Director Nancy Glaser says it draws people from around the world. The singer’s exhibit is so popular that it will probably be enlarged, she said.

Through posters and numerous photographs, museum visitors learn about the songs Brown wrote, which underlie his lifetime journey as a social activist.

“America is My Home” and “Say it Loud, I’m Black and Proud” are examples. “Living in America” was featured in “Rocky IV.”

Brown’s daughter, Deanna Brown Thomas, serves on the museum’s board of trustees. She and other Brown children continue her father’s philanthropic projects, which include giving away hundreds of turkeys on Thanksgiving and toys for children at Christmas.

In 1968 after the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., Brown televised a live concert from Boston that aimed to prevent rioting.

Visitors also can hear him sing several numbers, including one with the Italian tenor Luciano Pavarotti.

Knicknamed “the hardest working man in show business,” Brown often did 300 concerts a year. One of his best-known quotes is displayed in the museum: “When I’m on stage, I’m trying to do one thing; to bring people joy just like church does.

“People don’t go to church to find trouble, they go there to lose it.”

Brown was born in Barnwell, S.C., and was sent to live with his Aunt Honey, who ran a brothel in Augusta. To earn money, the story goes, he danced for soldiers at Fort Gordon near Augusta, shined shoes, picked cotton, and washed cars.

“I was determined to make something of myself, ” he later said.

His turn to religion led him to the church choir, where he developed a unique emotive voice.

His life was not all music and dance steps. His brushes with the law are not covered in the museum displays. “We set up the exhibit as The Man, His Music, and His Legacy,” Ms. Glaser explained as the reason for the omissions.

He organized a gospel choir behind bars, where he met Bobby Byrd, who invited Brown to join the Gospel Starlighters. Later, it was renamed the Famous Flames for Georgia night club engagements.

On his energetic concert tours, he sang the praises of his black roots and of America.

Brown knew the impact his music made.

“Others may have followed in my wake, but I was the one who turned racist minstreling into black soul, and by doing so became a cultural force,” he said.

Mary Alice Powell is a retired Blade food editor. Contact her at: mpowell@theblade.com