DEADLY ALLIANCE: WEAPONS OVER WORKERS

Coal town hit hard by black lung now struggles with beryllium disease

12/27/2012

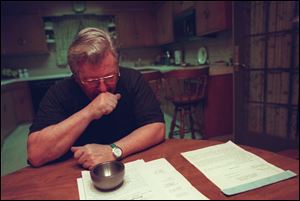

Another Hazelton worker and beryllium victim, Al Matusick, visits the razed site of the former plant.

BLOCK NEWS ALLIANCE

Carmen Fornataro was one of the first machinists hired at the beryllium plant at Hazelton, Pa. He says people were desperate for good-paying jobs in the coal-mining town that had been hard hit by black lung and mine explosions. Mr. Fornataro was diagnosed with beryllium disease in 1988.

HAZLETON, Pa. -- For decades, this old coal town in the northern reaches of Appalachia was hit hard by black lung.

Scores of miners developed the disease by breathing in the dangerous dust. Fathers got it. Sons got it. And, sometimes, their sons got it.

"Between the mine explosions and black lung, good portions of families were wiped out," resident Carmen Fornataro says.

Now, residents are suffering from another deadly dust: beryllium.

"The beryllium plant was supposed to be high-tech and safer than the mines," former employee Carol Zamba says. "The only difference was that this dust you couldn't see; so people didn't think it was dangerous."

About a dozen people here have been diagnosed with beryllium disease, an incurable lung ailment caused by inhaling microscopic bits of beryllium.

Sixty-five others have abnormal X-rays or blood tests that are consistent with the illness, a recent study shows. That's about 15 per cent of the former beryllium workers tested -- one of the highest rates ever found.

"We were expecting 5 per cent at the most," says Dr. Kenneth Rosenman, a professor of medicine at Michigan State University.

DEADLY ALLIANCE: How government and industry chose weapons over workers

The good news is that people in Hazleton are no longer being exposed to the dangerous metal: The local plant closed in 1982.

But because beryllium disease often takes years to appear, cases continue to be discovered among former workers.

Ironically, beryllium came to this town of 25,000 in eastern Pennsylvania with great fanfare.

The year was 1957, when area coal mines were all but depleted. Unemployment had soared to 25 per cent.

Civic boosters started wooing outside business, landing the Beryllium Corporation, a firm that had just signed a major U.S. defense contract and needed to expand.

By then, the hazards of beryllium were clearly known. In fact, Beryllium Corporation's plant just outside Reading, 40 miles to the south, had recorded several deaths from beryllium disease.

Another Hazelton worker and beryllium victim, Al Matusick, visits the razed site of the former plant.

Still, Hazleton leaders welcomed a beryllium plant.

"I didn't think I was putting people in danger," recalls Dr. Edgar Dessen, the then-chamber of commerce president who helped bring the plant to Hazleton. "I felt I was doing the proper thing, medically and morally."

Now 82 years old and a retired radiologist, Dr. Dessen says he was assured the plant would be safe and closely monitored by the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission.

"They had very stringent rules," he says.

The business moved into an old, horseshoe-shaped building outside of town. Dignitaries posed for pictures. The local paper proclaimed Hazleton was entering "the atomic age." And workers lined up for jobs.

"Holy God! Everyone and their brother wanted to work there," says Mr. Fornataro, one of the first machinists hired.

The 69-year-old says workers were told that beryllium was hazardous, but they didn't seem to care.

"People were so desperate for jobs, it didn't mean a thing," says Mr. Fornataro, who was diagnosed with beryllium disease in 1988.

Like the plant outside Reading, the Hazleton factory had high amounts of beryllium dust in the air, government and scientific reports show. Some dust counts were 4,000 times the safety limit.

Former plant secretary Ms. Zamba recalls wiping dust off her desk every morning.

"Had I known I would be exposed, even in an office atmosphere, I would not have taken a job there."

Luckily, she says, she didn't develop the disease.

Al Matusick wasn't so fortunate. He was diagnosed in 1983. He now has a chronic cough and shortness of breath.

He recalls how workers often had to be evacuated from the plant.

"There were powder spills -- I mean huge ones," the 67-year-old says. "It would take 24 hours for the dust to settle."

In 1985, Mr. Matusick and other victims sued then-owner Cabot Corp., but the suit was dismissed because they couldn't prove they were intentionally harmed.

Cabot, a Boston-based chemical firm, declined to comment. It tore down the plant a few years ago but still owns the land.

Mr. Matusick is still fighting the company, and he takes a visitor out to the old plant site to show why.

Down a winding, gravel road, past strip mines and slag heaps, is a large pond. There, dozens of dead, pale trees stick out of the black water.

"Look how dead everything is," Mr. Matusick says. "It's gruesome."

He blames runoff from the nearby beryllium site, but health officials say drainage from abandoned coal mines -- not beryllium -- is killing off the life.

Perhaps the most frustrating issue for victims here is workers' compensation, the insurance system for workers injured on the job.

Under Pennsylvania law, workers must file claims within 300 weeks of leaving their jobs.

But beryllium disease can take up to 40 years to appear.

Mr. Fornataro, for example, left the beryllium plant in 1974, but his disease did not appear until 1988 -- 14 years later.

So when he filed a workers' compensation claim, he was rejected because the statute of limitations had run out. He appealed in the Pennsylvania courts, but to no avail.

"It's the most ridiculous thing," he says. "How could somebody file for a disease when they don't know they have it?"

Dr. Rosenman, the Michigan State researcher, agrees. In most states, he says, the statute-of-limitations clock does not start ticking until victims discover they have the disease. Not so in Pennsylvania.

"A backward, inadequate law," he says.

Some residents say Hazleton would have been better off if the beryllium plant had never come to town.

"This was going to place Hazleton on the map, and people were going to be able to make big money, and live a life of grandeur," says Ms. Zamba, the former secretary. "It put Hazleton on the map, but in a very negative way."