Club drug shows promise as healer

10/23/2006

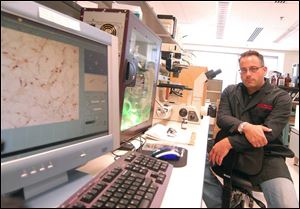

Jack Lipton, a professor of psychiatry at the University of Cincinnati, is exploring using Ecstasy for its therapeutic properties to aid people who suffer from Parkinson's disease.

Only a few years ago, Maryland researchers made national headlines with the news that the drug Ecstasy could cause Parkinson's disease.

Now an Ohio researcher has shown how the club drug may actually lead to a way to restore the parts of the brain that deteriorate in Parkinson's, the neurological disorder that makes hands unsteady, movement stiff, walking difficult, and even erase facial expression.

While the Maryland study was withdrawn when scientists realized they used the wrong drug, other labs were discovering Ecstasy could ease Parkinson's symptoms in animals.

Jack Lipton, professor of psychiatry at the University of Cincinnati, told a gathering at the Society for Neuroscience meeting in Atlanta last week that Ecstasy's impact may go beyond a reduction of symptoms. His research found Ecstasy actually increased the survival of neurons in rat fetal brain cells by 70 percent to 300 percent.

Most important for Parkinson's patients, these long-lived neurons are the same ones that deteriorate in Parkinson's - those that transmit the neurochemical dopamine. Dopamine is famous for its role in feelings of pleasure, but it also plays an important role in movement.

"We're really excited about this,'' said Mr. Lipton. "Who would have thought you could take a drug that's abused, and find therapeutic properties?''

No one is advocating Parkinson's patients find a street supplier, however. Ecstasy may damage neurons that transport seratonin, which regulates mood and sleep. Long-term use can lead to anxiety or depression, and it can cause fatal hyperthermia.

Researchers instead hope that the chemical structure of Ecstasy - known as 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine or MDMA - will serve as a basis for new compounds that produce Ecstasy's benefits without its deleterious effects.

Mr. Lipton's discovery of increased dopamine cell survival is an extension of his work in rats. He gave pregnant rats MDMA, then looked at the brains of the offspring 21 days after birth.

He wanted to see what would happen to dopamine neurons, which produce long spindly fibers along which they send out signals to other parts of the brain. His MDMA-exposed rats showed a three-fold to five-fold increase in the number of dopamine nerve fibers, compared to MDMA-free rats.

"I don't think I've ever seen a drug, any drug, produce dopamine fiber innervation in an animal. No one has seen it before. I know because I searched for it,'' Mr. Lipton said.

Mr. Lipton's research "has shown for the first time that an MDMA-like molecule could actually stop the death of dopamine cells. This is very exciting,'' said Jonathan Brotchie, a senior scientist at Toronto Western Hospital who works on MDMA-based compounds for Parkinson's treatment. He is also chief executive officer of Atuka Ltd., a company that develops Parkinson's drugs.

Ultimately, the development of MDMA for Parkinson's could come from a number of directions. Mr. Brotchie said he has developed compounds that curb Parkinson's symptoms in animals, but he believes those compounds work through serotonin neurons, not dopamine neurons.

Last year, researchers at Duke University in Durham, N.C., discovered that Ecstasy could reduce Parkinson's symptoms in mice. That group proposed neither serotonin action, nor dopamine activity as the reason, but suggested yet another chemical reaction behind the reduced symptoms.

"It's complicated,'' Mr. Brotchie said. "Brain science is harder than rocket science.''

"I think this work shows a great deal of potential,'' said Jon Sprague, an Ohio Northern University researcher who works on the toxic effects of Ecstasy. Mr. Sprague, a PhD in pharmacology and toxicology, is dean of the College of Pharmacology at the university in Ada.

The fact that the Cincinnati laboratory has moved from animal experiments to cell culture experiments "really gives you the ability to test the true mechanisms at work,'' Mr. Sprague said.

The Cincinnati researcher suggested that MDMA-based compounds could someday improve the prospects of fetal-cell or stem-cell transplants in Parkinson's patients.

Thus far, few cells survive transplantation, Mr. Lipton said.

"When you take 100,000 cells and place them in the brain, 3 percent of the cells will survive and actually innervate,'' Mr. Lipton said. Using MDMA to increase survival of these cells after transplantation, he added, is one possibility.

Creating a drug to treat the disease directly, without a cell transplantation, may be further off, Mr. Lipton said, but still within the realm of possibilities.

Contact Jenni Laidman at: jenni@theblade.com or 419-724-6507.