Novel surgery saves life of boy with curved spine

1/7/2007

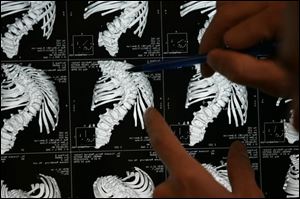

Dr. Aaron Buerk performed the surgery Caleb Manuel needed to straighten his spine and give his lungs room to grow. The X-ray on the left shows the device installed in Caleb s back.

Josh and Jessy Manuel play with son Caleb at home. Caleb was born with severe scoliosis, but recent surgery has allowed his radically curved spine to straighten significantly.

During his sixth week in the womb, Caleb Manuel was as small as a raspberry and perfectly formed, with a fetus round otherworldly head and the buds of a developing nose, ears, and toes.

Every day, the unborn child of Toledoans Jessy and Josh Manuel grew a millimeter. Then, sometime during the next three weeks, Caleb s unfolding took a wrong turn. It may have been an infection. It may have been something else.

Dr. Aaron Buerk, a pediatric orthopedic surgeon, calls it simply a developmental hiccup, but a hiccup with timing so critical it would have profound effects.

Slowly, Caleb s spine was curving his delicate body into a little comma.

Instead of growing into a stack of blocks as it should, his spine was forming a mixture of blocks and wedges. Two of the ribs on his left side simply did not grow. Eight of the remaining ribs grew fused together in two bony clumps.

Dr. Aaron Buerk performed the surgery Caleb Manuel needed to straighten his spine and give his lungs room to grow. The X-ray on the left shows the device installed in Caleb s back.

Together, the ribs acted as a tether, drawing the spine like a bow.

Caleb s very life was the arrow poised to be shot and lost.

If anyone should have had a healthy baby, it was Jessy and Josh Manuel. Jessy was 19, slender and pretty. Josh, 22, was an athlete with an athlete s build. They had married just after Christmas in 2003, the continuation of a love story that began as a friendship when Jessy was 15 and the two were members of their church youth group.

The couple wanted children, four of them.

Jessy would stay home and raise them while Josh worked as engineer for the industrial engineering consulting firm IUT Inc.

CT scans of Caleb Manuel s spine show the severity of his scoliosis before surgery. The 120-degree curve has Caleb s ribs pressed almost to his spine. Note the vertebrae become chunky and misshapen in the center of his back. The ribs to the left of the spine are fused, furthering the curve s severity.

When Jessy s first pregnancy began to accumulate complications, the couple bore it with a mixture of realistic fear, abiding faith, and the optimism of the young and untested.

Jessy had too much amniotic fluid. Only one umbilical artery stretched from her to her infant instead of two.

Then an ultrasound revealed the infant was missing a kidney and had a slight curve in his spine.

I almost passed out, she said of the defects news. I went home crying.

They were shocked. The perfection young couples anticipate so routinely was denied to them.

Their obstetrician assured them that people can live long lives with a single kidney. And scoliosis? Jessy had a sister with scoliosis.

No big deal, Jessy concluded.

The ultrasound s revelations, and the other complications, required closer monitoring of Caleb s health. Once a week, nurses at the obstetrician s office wrapped a thick belt around Jessy s swelling abdomen and checked Caleb s heart rate. Caleb didn t like it at all.

He d kick it all the time, Jessy said. He was so active.

Despite Caleb s objections, monitoring was increased to twice a week. On Dec. 6, 2004, three weeks before his due date, the monitor told Jessy she was in labor.

She was in the Toledo Hospital obstetrics ward within hours. Josh rushed back from a job site in Sandusky, hoping to arrive before the baby. The baby, however, was in no hurry.

By midnight, the obstetrician said they should wait no longer. She broke Jessy s water.

Jessy watched as alarm registered on her doctor s face. The doctor punched a button on the fetal monitor and commanded, We re going.

Caleb s heart rate was plummeting perilously. While a stunned Josh watched, they wheeled his wife away with their baby inside her.

The operating room filled quickly with people as the obstetrician prepared to perform a Cesarean section.

A nurse took a wedge of Jessy s flesh between her fingers and pinched.

Do you feel this?

Yes. The injection of anesthetic into her spine had not yet taken effect. They placed a mask over Jessy s face.

I just breathed it all in. I wanted to go to sleep so they could get my baby.

Is my baby OK? Is my baby OK? Jessy babbled as she woke.

Don t worry, Josh whispered, Everything is OK. I m here.

He had seen Caleb. His little boy was a tiny, swaddled bundle, 4 pounds, 10 ounces, 17 inches long. Now nurses brought the baby to her.

Groggy from her drugged sleep, she saw a beautiful little face sticking his tongue out and blowing bubbles.

But something seemed wrong.

My voice was all scratchy. I thought I was scaring him, she said. He seemed to be struggling for breath.

He can t breathe! she said.

But her baby could breathe. What he couldn t do was swallow. Doctors soon learned his esophagus wasn t connected to his stomach.

Less than 12 hours after his birth, Caleb was in surgery to stretch his esophagus to his stomach and to repair an opening between his esophagus and his trachea.

The surgery should take three hours, the couple was told. By the fourth hour, the tension in Jessy s room was palpable. The couple s parents, grandparents, siblings, aunts, and uncles kept watch with them.

That s when Dr. Buerk walked into the crowded room.

His news was alarming. Their baby had the worst case of scoliosis he had ever seen. Caleb s spine was bent 30 degrees.

Caleb s scoliosis isn t like the kind more typically encountered in children and teens. In those cases, the ribs are normal, the spine looks normal. It simply curves. It s possible for an adult to have a spinal curve of 30 degrees without anyone noticing anything wrong.

But Caleb s ribs and spinal configuration guaranteed he would continue to bend as he grew.

If he was 30 degrees at birth, in a year or two, he would be 90 degrees, 100 degrees.

The fate of children born with this defect has been tragic. As the spine continues its bend, the lung the spine bends toward runs out of space. Even the lung on the opposite side of the bend is squeezed. The spinal curve ultimately denies these children the lung capacity to carry them into adulthood, or even into adolescence.

The typical operation for scoliosis a fusion of the spine itself is out of the question for these babies. Once the spine is fused, it stops growing. More significantly, fusion does nothing to give the lungs room to grow.

But the young doctor giving the Manuels this bad news also carried the answer to their prayers before they even prayed them.

Just before he arrived in Toledo in 2004, Dr. Buerk had completed a fellowship in pediatric orthopedic surgery at Boston Children s Hospital under Dr. John Emans.

Dr. Emans was one of the few surgeons in the country working with a device to repair curvatures like Caleb s. Dr. Buerk had been part of the team, performing some procedures, assisting in others.

Yet the dire diagnosis swamped all thought of some future surgery for Jessy and Josh. When Dr. Buerk left, Josh asked everyone to step out of Jessy s room.

Alone, the couple broke down and cried.

Then they prayed.

You told us you wouldn t give us more than we could handle, Josh prayed. This is it. We re at our limit.

As each prayed, they felt a growing peace.

Moments later, they learned Caleb s surgery was a success. His esophagus was reconnected.

Caleb would remain in Toledo Hospital s Neonatal Intensive Care Unit for six weeks before the couple could take him to their Douglas Road home to begin their difficult journey together.

Caleb Manuel recovers from his Sept. 6 surgery at Toledo Hospital to straighten his spine and give his lungs room to expand.

The next two years were a welter of medical worries and hospital visits, woven into the more usual triumphs of babyhood. Caleb learned to stand. He learned to walk. He responded to his parents and their friends at church with all the liveliness they had dreamed of.

But he was not gaining weight. And weight gain was essential if he was to receive the life-saving spinal surgery.

Dr. Buerk wanted to insert an expandable metal device along Caleb s spine. The Vertical Expandable Prosthetic Titanium Rib would attach to Caleb s spine near his waist and extend to nearly the top of his rib cage, where it would be hooked to his ribs at about shoulder height. This device would open Caleb s chest, making room for his lung, and straightening his spine significantly.

Only baby fat could protect Caleb from having the device protrude through his skin, but Caleb didn t have any.

Doing this surgery early was essential, Dr. Buerk said. By age 5, all the tiny little air sacs that carry us into adulthood have formed. If lung growth is stunted during this developmental window, it will never recover.

Perhaps more importantly, Caleb s curvature was rapidly increasing.

Jessy would walk through the grocery store with Caleb slouching in his baby seat, and other shoppers would stop her and suggest she sit her baby straighter. But for him, this slump was straight.

Such encounters upset Josh. He knew his wife was a good mother, and he was protective of his wife.

It s probably because she looks so young to have a child, they think she doesn t know what she s doing, he said.

They re just trying to be helpful, Jessy said.

No amount of good mothering, though, could get Caleb to eat. Doctors put a tube into Caleb s stomach, but he threw up almost as much as he took in. They tried a tube directly into his small intestine, but it clogged and was removed in less than a month.

They tried the gastric tube again. This time it worked, and Caleb started eating soft foods by mouth.

Dr. Buerk wanted Caleb to be 20 pounds for the surgery. He weighed only 18 pounds by September, but there was no more time to lose. On Sept. 6, Caleb was wheeled into surgery.

His spinal curve was now 120 degrees one-third of a circle. When he stood, his shoulder nearly rested on his hip.

In the operating room, nurses arranged Caleb on his side and Dr. Buerk began the first spine-repair operation of this type in Toledo.

The doctor confessed a little bit of extra tension. The last thing you want for your first case in a new area is for it be the worst one you ve ever seen, he said.

Dr. Buerk began by making a long L-shaped incision from the top of Caleb s shoulder blade, down along the spine, and then out to the top of the pelvic bone.

Drawing back the skin, he now had access to the muscles surrounding the chest. These he cut right at the point where they attach to the spine.

Dr. Buerk had been following Caleb s development since birth; a stream of CT-scans and X-rays revealed how Caleb was bending like a sapling in a hurricane. But now the surgeon saw how truly profound Caleb s deformity was.

It s actually pretty rare to have this degree of severity, he said.

The surgeon s next task was to separate Caleb s ribs. The toddler had two clumps of rib, each made from four fused bones. Dr. Buerk separated them to create six ribs.

Instantly, Caleb s lung leapt into the newly opened space. The anesthesiologist even sensed the change, as Caleb s breath came more easily.

But now the lung had to be prevented from emerging between the ribs. Dr. Buerk sewed a synthetic porous membrane over Caleb s newly liberated lung, then turned to the installation of the expandable titanium rib.

The device was light in his hand. Opened to its full extent, it would be about a foot long.

Dr. Buerk attached the device s two ends one to the spine, at about waist level, the other to an upper rib and connected them.

Now to expand the device. Just how far to extend it is the trickiest question of the entire operation. Dr. Buerk wanted to open it as far as he could. The longer the device stretches, the more the spine is straightened. But open it too far, and the spinal cord stretches, a tension it cannot tolerate.

Monitors sent signals from Caleb s head to his toes and back again, assuring the spinal cord continued carrying its messages, providing Dr. Buerk with a guide.

He lengthened the device to 8 inches.

Caleb left the surgical suite six hours after the operation began 2 or 3 inches taller than he went in. The 120-degree curve was now a mere 40 degrees.

Every six months, Dr. Buerk will make a small incision and expand the device a centimeter or so, pacing it to Caleb s growth.

By age 5, Caleb should outgrow this device and be ready for a second, larger one. By the time Caleb is 14, he will be on the last of three or four devices. His chest will be open, his lungs fully functioning. At this age, his spine will stop growing, as it does in all children, and most of his growth will come from his legs. Now, his spine can be fused, allowing further straightening.

As Caleb recovers from surgery, he reaps subtle benefits from his new posture. Before his bend forced him to walk with his shoulder tipped, his head to the side. Now, his head high, he can gaze at people directly with big blue eyes, his spiky blonde hair a mane of exclamation points to his inquisitive looks.

He s far more playful and talkative than he was before the operation, Dr. Buerk said. And his new lung capacity has improved his stamina.

It s a blessing, Jessy and Joshua said, one of those miracles for which they cannot stop being grateful.

But of all Caleb s improvements, there is one that carries a special poignancy. He can do something that was too painful for him to do in the past.

In the living room of their home, decorated with the primary-color toys of a toddler, Caleb demonstrates his new skill.

He toddles up to Jessy, and gives his mother a hug.

Contact Jenni Laidman at: jenni@theblade.com or 419-724-6507.