NOT WHAT THE DOCTOR ORDERED

Health insurers describe business as balancing act

Interests of doctors, patients clash with employers

8/26/2008

Third of four parts

A technician prepares a patient for an MRI at the former Medical College of Ohio. Steady increases nationwide in medical imaging services, as well as safety concerns, led insurers to require preauthorization.

A decade ago, Dr. Barry Malinowski prescribed antibiotics to sick children who didn’t need them because it was the customary treatment.

Pressure from parents played a part too.

Widespread use of antibiotics for colds and other viral infections, however, resulted in problems with drug-resistant bacteria, one example of how medical overuse can unintentionally cause harm. Viral infections are not cured by antibiotics, and doctors now recognize that using them fosters resistance to bacterial strains.

“That was a problem, I think, 10 to 20 years ago,” Dr. Malinowski said. “I think we were all guilty in not using enough discretion.”

The pediatrician added: “I’m as guilty as the next guy down the street.”

These days, Dr. Malinowski is medical director in Ohio for Anthem Blue Cross and Blue Shield, owned by the nation’s second-largest health insurer, WellPoint Inc. He continues to practice while working for Anthem, where he helps make decisions about what the largest health insurer in Ohio will cover and safeguards against excessive health-care usage.

At an estimated $2.4 trillion this year, costs of the U.S. health-care industry have doubled in the last decade, increasing scrutiny and demands for efficiency in both the private and public sectors. Total spending on health care could increase from 16 percent of the gross domestic product last year to a quarter in 2025 - and nearly a half by 2082, predicts the Congressional Budget Office.

What doctors want for their patients and what is paid for by insurers are often at odds because of questions about medical necessity as well as cost, Anthem and other insurers say. Insurers have to keep the interests of not only doctors and patients in mind, but of those footing the bill for insurance coverage, they say.

“It’s a balancing act,” Dr. Malinowski said. “Sometimes, we are in the middle because we have a number of parties we have to serve.”

READ THE SERIES: Not What The Doctor Ordered

An eight-month Blade investigation, including interviews with about 100 physicians in a dozen states and a national survey of doctors with more than 900 responses, revealed that a growing number of doctors believe there’s an epidemic of insurers dictating medical-treatment decisions.

Physicians in the survey and in interviews expressed the same worries that their clinical decisions are increasingly overruled by insurers, at times harming their patients.

The delays and denials affect all types of patients in a multitude of ways, doctors said.

The ‘bad guy’ role

Ninety-nine percent of the 920 respondents to The Blade’s unscientific survey of Ohio State Medical Association and American Medical Association members indicated insurers interfered with some aspect of their treatment plans for patients. The associations sent The Blade’s online questionnaire to their members.

Ninety-five percent of respondents said insurers interfered with decisions about prescriptions, 91 percent with testing, 74 percent with referrals, and 69 percent with hospitalization decisions.

Eighty-six percent said insurer interference compromised patient care, with 14 percent reporting they believe interference had contributed to the death or serious injury of a patient.

But, insurers insist, preauthorizations aren’t designed to interfere with the doctor-patient relationship.

Sometimes, preauthorizations help detect overuse or even suspected illegal activity. Paramount Health Care’s preauthorization requirement for the painkiller OxyContin - commonly known as “hillbilly heroin” - revealed an area doctor who wanted to prescribe an unusually large amount of the notoriously abused narcotic about a year ago. The doctor was reported to the state medical board.

Paramount officials declined to comment further on the suspicious OxyContin-prescribing doctor, citing privacy reasons.Sometimes, safety plays a role. Anthem Blue Cross and Blue Shield started requiring preauthorizations for CAT scans and MRIs after three years of more than 20 percent usage increases, raising concerns about whether patients were being needlessly exposed to radiation from imaging tests. Requests to Anthem have stabilized since, and less than 2 percent of CAT scans and MRIs, and other advanced scans are denied, the company said.

Radiation to a patient’s stomach from an abdominal CAT scan is at least 50 times greater than that from a conventional X-ray, for example, and studies show virtually all patients get more than one scan in a session, according to a November article in the New England Journal of Medicine written by researchers at the Center for Radiological Research at Columbia University Medical Center.

Cancer risks for any one person are not large, but the increasing usage of CAT scans and exposure to radiation may become a public-health issue, the article states. The risk is especially a concern for children, both because they are more radiosensitive and have more years to develop a radiation-induced cancer, according to the article.

Without insurers providing oversight, U.S. health-care costs likely would climb even higher, said Dean Smith, professor of health management and policy at the University of Michigan.

Insurance is a way for all participants to pool risks and balance costs, and insurers often assume the “bad guy” role when it comes to making sure expenditures are not excessive or fraudulent, Mr. Smith said.

It’s especially crucial with self-funded insurance plans, in which insurers administer large employers’ health programs, added the director of UM’s Center for Value-Based Insurance Design.

“They get paid for taking the role,” Mr. Smith said. “No one likes the enforcement role when it’s applied against them, and insurance companies understand that, by and large.”

Paramount President John 'Jack' Randolph, left, with the firm's vice president for marketing, Mark Moser, says his company has a strong relationship with doctors, who help with operational and policy decisions. 'It doesn’t mean we don’t . . . have issues that come up,' Mr. Randolph says.

A big business

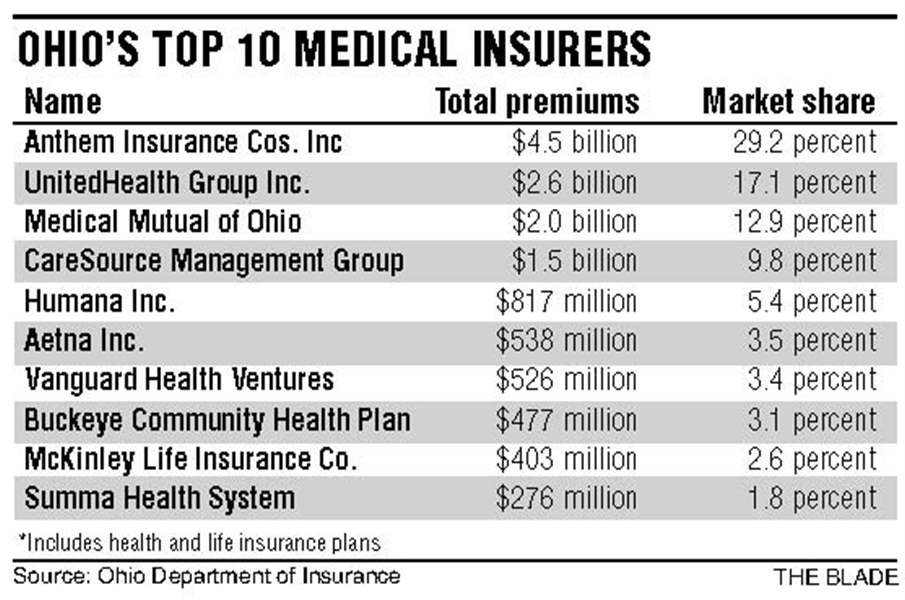

No one can dispute that health insurance is big business. Private health insurance alone accounts for about third of U.S. health expenditures, or more than $723 billion, according to the latest federal statistics.

Publicly traded insurance companies typically have an annual profit margin of 3 percent to 7 percent, although for the first time in several years, one company - Health Net Inc. - reported a first-quarter loss this year after accounting for litigation and restructuring charges, said Rick Byrne, market analyst at HealthLeaders-InterStudy.

The country’s largest health insurer is UnitedHealth Group Inc., a Fortune 50 firm making inroads in northwest Ohio with its UnitedHealthcare company. The public Minnetonka, Minn., company covers roughly 70 million Americans and works with 560,000 doctors. It had $75.4 billion in revenues last year - and $4.7 billion in profits, a 6 percent margin.

The vast majority of UnitedHealth’s revenues come from traditional insurance premiums, where the company assumes the risk for both medical and administrative costs, according to the company’s annual report filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission.

“The profitability of our risk-based products depends in large part on our ability to predict, price for, and effectively manage health-care costs,” the report says.

Between 80 percent and 85 percent of those premium revenues typically are used to pay costs of health-care services for UnitedHealth customers, it said. The remaining 15 percent to 20 percent are earnings used to pay salaries for about 67,000 employees, and covers other overhead.

Executive compensation

Running such a company isn’t cheap, but insurers argue they need to pay well to attract and retain top executives. UnitedHealth President and Chief Executive Stephen Hemsley’s salary was $1.3 million last year, part of a total compensation package worth more than $13 million, according to another SEC filing.

Of course, that is small compared to Dr. William McGuire’s total compensation of $124.8 million, including a $2.2 million salary, as UnitedHealth chief executive in 2004. Dr. McGuire was forced out of the company in 2006 amid a scandal involving backdating stock options, which for him were valued at more than $1 billion, and he agreed last year to pay back more than $600 million.

By comparison, Maumee’s Paramount had nearly $601 million in revenues last year. John “Jack” Randolph, president of the insurance arm of Toledo’s ProMedica Health System, had total compensation of $587,179 in 2006 , the latest year for which financial information on the private company is available.

Ohio has 135 licensed health insurers, led by Anthem parent WellPoint and UnitedHealth.

Nationwide, WellPoint had $61.1 billion in revenues and $3.3 billion in profits last year, a margin of 5 percent. Last year, Angela Braly received nearly $9.1 million in total compensation, including a $922,269 salary, for serving a half year as executive vice president and a half as WellPoint’s president and chief executive, according to SEC documents.

Ms. Braly’s predecessor, Larry Glasscock, had total compensation of $23.9 million in 2006, including a $1.3 million salary. His 2007 total compensation was $9.6 million, documents say.

More than 225 million Americans are covered by health insurance, either through private or public plans. An estimated 75 million Americans either lack adequate insurance or are uninsured.

Under pressure

Insurance plans are not alone in worrying about their bottom lines, industry experts say.

Both insurance payers and doctors are under financial pressure, and those distresses are interlaced, explained J.B. Silvers, research director at Case Western Reserve University’s Health Systems Management Center.

Doctors, he said, started seeing their incomes compromised in the early 1990s, when the federal government scrutinized and trimmed reimbursements for Medicare, the insurance program primarily for those 65 and older.

Most insurance plans base their reimbursements on payments from Medicare, so doctors took financial hits from that side, too, he said.

Just last month, doctors narrowly escaped a 10.6 percent Medicare reimbursement cut after Congress intervened after weeks of stalling.

The issue routinely comes up because a Balanced Budget Act of 1997 formula requires payment cuts to doctors and hospitals when spending exceeds goals.

To make up the income difference in the last decade and a half, Mr. Silvers said, doctors have billed for more procedures and tests performed in their offices.

That high utilization was amplified by soaring malpractice complaints, which prompted doctors to practice defensive medicine to cover themselves legally and financially, he said.

“You had a whole bunch of forces who said, ‘You’ve got to do more,’ ” Mr. Silvers said.

Insurance companies for a time passed those additional costs onto buyers in the form of increased premiums, Mr. Silvers said.

But employers and other buyers started bucking at soaring double-digit annual premium increases in the late 1990s, causing them to cut back on coverage or to seek other plans, so insurers put restrictions on doctors, he said.

Taking a hit

In the Toledo area, union retirees of various companies who expected coverage for life have been especially hard hit by reduced health benefits.

Pilkington, which acquired Toledo’s iconic Libbey-Owens-Ford Co. in 1986 and now is owned by a Japanese firm, made various changes to retiree health benefits within the last decade. As the glass-maker’s health-care costs related to retirees of the former L-O-F ballooned from $21.6 million to $30 million annually in five years, for example, retirees were forced to begin paying part of their monthly insurance premiums.

One example of resulting insurance company restrictions is the preauthorizations Anthem and other insurers started requiring for CAT scans and MRIs, which more doctors were installing in their practices.

In Ohio alone, radiology utilization was increasing 15 percent to 18 percent a year, Anthem officials said. Companies did a good job of selling the equipment, and doctors then naturally want to use the machines to justify their purchase, but there has to be a balance.

Even Medicare is trying to cut down on rising medical imaging costs, which more than doubled to about $14 billion a year between 2000 and 2006. More was being spent on imaging done in doctors’ offices, and wide variations in imaging spending indicate there may be overuse in some areas, according to the Government Accountability Office.

Medicare spending on in-office imaging per beneficiary ranged from $62 in Vermont to $472 in Florida, according to the GAO. In-office imaging costs in Ohio were $185 per Medicare beneficiary and $258 in Michigan.

The magnitude of the insurance industry is reflected in part by executive compensation. WellPoint leader Angela Braly received a total of $9.1 million last year. Her predecessor, Larry Glasscock, received $23.9 million in 2006.

More care vs. better care

The belief that doctors always know best, Case Western’s Mr. Silvers and other industry experts said, started to be shattered in the eyes of payers by findings of the Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care. The Dartmouth College project has used Medicare data to document wide geographic variations in medical care and corresponding costs, showing that more care does not necessarily mean better care.

Insurance payers typically do not pay for experimental treatments because they are not proved to be effective, and they use evidence from medical studies to help make coverage decisions.

Technology advances so rapidly that there often is a gap before insurance payers are willing to cover new procedures or tests, said Dr. Lance Talmage, a Toledo gynecologist.

Patients often want to use the latest - and typically costly - technology even if it is unnecessary, Dr. Talmage said. And doctors are not well versed on cost-benefit issues, he said.

“They look like they’re resisting change,” Dr. Talmage said of insurance companies. “They are resisting it, but they’re resisting it with some legitimacy.”

Dr. Lurley Archambeau, a Monclova Township psychiatrist, has seen the struggle from both sides. He helped start a local managed-care company for mental-health coverage in the late 1980s, when care was so inefficient that an insurance company was billed for a few months of hospitalization for a patient with an eating disorder even though she was allowed home most of the time.

Managed care, Dr. Archambeau said, has gone too far, though. Dr. Archambeau said he knows of one psychiatric patient who was sent home because the patient’s plan to commit suicide involved jumping out a second-floor window, which would not have been fatal. “It’s changed medicine,” Dr. Archambeau said. “The physician has become a commodity.”

‘Healthy tensions’

Mr. Randolph says Paramount has a strong relationship with physicians in part because it is a provider-sponsored plan, with doctors serving on Paramount councils and on its board.

Physicians also help with both operational and policy decisions, Mr. Randolph said. Paramount has more than 2,000 doctors in its network.

“It doesn’t mean we don’t, as with any situation, have issues that come up,” Mr. Randolph added. “As you’re trying to do the best thing for our clients, there are going to be a variety of healthy tensions.”

If an insurer’s internal appeals process is exhausted, doctors and patients can appeal to the federal or state government, depending on the type of plan involved. Medicare appeals, for example, are handled through the federal Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

Ohio residents with commercial insurance policies and government employees can turn to the Ohio Department of Insurance to request reviews of health-care denials. If appeals are approved, insurers must provide coverage and pay for the reviews.

Independent review organizations accredited by the department reversed 57 of 156 insurance denials based on medical necessity or experimental treatment in 2006, the latest year for which statistics are available. The insurance department in 2006 reversed 24 of 159 cases it reviewed to determine whether services denied, reduced, or terminated by the insurer should be covered under the contract.

The independently reviewed reversals involved nearly $1.9 million in claim denials, primarily for surgery and hospitalization, with the top five cases saving Ohioans more than $1.4 million, according to the insurance department.

Those top five reversals included a $739,000 bone marrow transplant disputed by Anthem, the largest case. Other reversed cases included a $300,000 neuroform stent for a brain aneurysm challenged by Coventry Health and Life Insurance Co., and a $200,000 blood stem cell transplant to treat myelodysplastic syndrome that had been denied by SummaCare Inc. of Akron.

More than 20 million claims are processed annually, but little more than 1,000 cases have been disputed since the state program went into effect eight years ago, noted Kelly McGivern, president and chief executive of the Ohio Association of Health Plans.

“The role of the health insurer is to pay for quality health care - really, really quality health care,” she said. “We do have a checks and balances type of a system.”

Blade staff writer Steve Eder contributed to this report.

Contact Julie M. McKinnon at:jmckinnon@theblade.comor 419-724-6087.