Minority veterans face additional post-service issues

Area servicemen cite challenges reintegrating after war’s horrors

7/8/2013

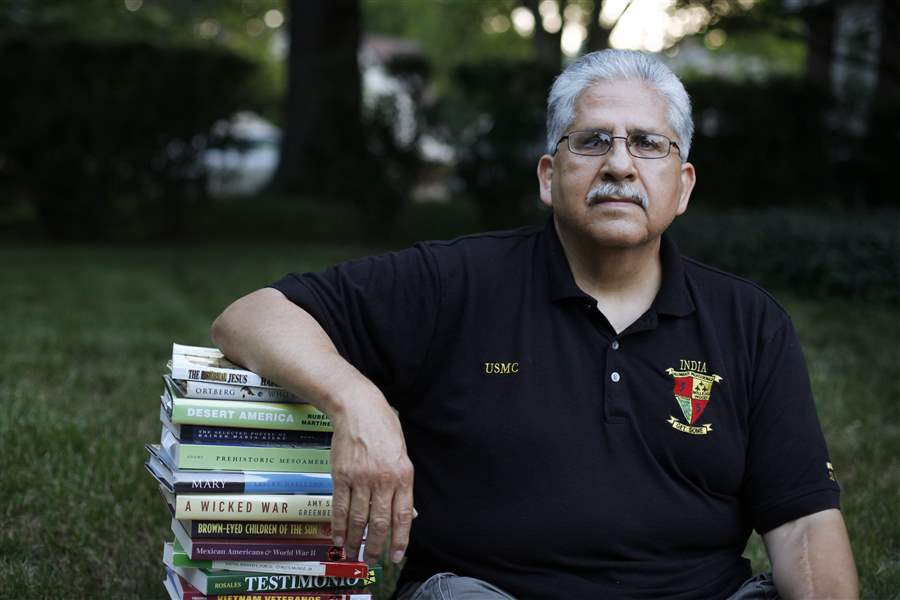

Manuel Caro, 66, of South Toledo says he has found healing through reading. His first therapist after Vietnam ignored his cultural background, he said.

THE BLADE/JEFFREY SMITH

Buy This Image

Manuel Caro, 66, of South Toledo says he has found healing through reading. His first therapist after Vietnam ignored his cultural background, he said.

Second of two parts

He still hears the screams, sees the agonizing facial expressions on his friends as they die, feels the blood splattering across his face. Absentmindedly, he starts to wipe away at the lenses of his glasses.

“We were walking in single file toward a large hill, or mountain,” recalls Manuel Caro, 66, of Toledo as he slowly begins his story. “The jungle was so thick you couldn’t see anything above or next to you. That’s when all hell broke loose.”

Corporal Caro, then 19, was a part of the 5th U.S. Marines, 3rd Battalion, India Company. They had been in Vietnam less than a week and had been ambushed by the Viet Cong twice.

“They started mortaring us; 50-caliber machine guns,” Mr. Caro says, as his voice begins to quiver. “People were falling left and right. People were screaming and dying.

“We had a lot of wounded but couldn’t get them out because they were shooting the helicopters.”

PART ONE: Local veteran's story illustrates struggles of post-traumatic stress

The 3rd Battalion couldn’t see where they were shooting; their ammunition was unable to penetrate the thick jungle brush.

The U.S. troops would learn later that the North Vietnamese soldiers were perched higher, shooting down at them.

The survivors spent the night surrounded by the dead bodies of their fellow Marines as the Viet Cong continued to fire at them, says Mr. Caro, his voice rising as he proceeds with the story.

He and another survivor attempted to dig trenches to bury the dead.

“We couldn’t dig enough holes, we couldn’t dig them deep enough,” Mr. Caro says, as he begins to sob, his whole body trembling with grief. “There were too many of them. They wouldn’t all fit. They were all dead.”

The color of war

“I’m telling our story of being poor and Mexican, and how we became seduced into fighting these wars for other people,” he said. “I joined the Marine Corps because I was seduced into believing in this American Dream, be patriotic, to be a real man."

The military recruiters make it sound so romantic: You get to see the world, develop leadership skills, get a free college education, and develop job skills, he said. Those promises sound pretty attractive, especially to poor Mexicans and African-Americans, he said.

Every year there are events where they put old, refurbished military vehicles on display, there’s a parade, and some politicians say a few words.

“That’s not the military,” Mr. Caro said. “That’s not what war is like. That’s not the truth.”

■ U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, Toledo office: 419-259-2000

Therapy and other services available, can answer eligibility questions.

■ Department of Veterans Affairs, Ann Arbor: 734-845-5275

■ Lucas County Veterans Service Commission: 1301 Monroe Street, Toledo, 419-213-6090

Provides temporary emergency financial assistance, transportation, death benefits, and Veterans Affairs Application Assistance.

■ For more information about the Arms Forces, contact Pam Hays at 419-891-2111, visit the organization’s Web site at www.thearmsforces.org or its Facebook page at facebook.com/thearmsforces

Offers support for veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder and traumatic brain injury and support for the families of veterans.

Returning home

Vietnam veterans like Mr. Caro had nowhere to turn to after they returned to civilian life.

The military didn’t offer therapy for post-traumatic stress orders until 30 years ago, said Sheila A.M. Rauch, director of Serving Returning Veterans’ Mental Health, a program offered through the Veterans Affairs Ann Arbor Healthcare System.

After his discharge, a disillusioned Mr. Caro joined Vietnam Veterans Against the War and threw away all his medals, including the Purple Heart he received during his last mission.

For most of his life, Mr. Caro seethed with anger, rage, and resentment. He was a college history professor and university administrator at various campuses. But the feelings never subsided.

Mr. Caro was in his late 30s when he tried to talk to a therapist, but the session did not go well.

The therapist did not understand why the veteran wanted to talk about his culture, and Mr. Caro became furious that the therapist insisted on ignoring it.

He would be 62 before he visited another therapist. They had a lot of ground to cover.

Corporal Caro led a six-man troop on a mission that went awry. Two were killed in the ambush. His best friend, who sat next to him in the helicopter, slumped onto him after being hit by a sniper. One of the three survivors committed suicide. All six Marines were Mexican-Americans and African-Americans.

“When I was recovering in the hospital, it just exploded, and I start seeing all the lies and contradictions as I started reading about war and racism, especially involving African-Americans and Chicanos,” he said.

The military prides itself on projecting a strong image, and most people don’t like to admit they need help, said Derek D. Atkinson, public affairs officer for Veterans Affairs Ann Arbor Healthcare System.

In Mr. Caro’s case, his therapist needed to address his patient’s deep-rooted anger and frustration, his feelings of being taken advantage of as a Mexican American, and the discrimination he re-encountered after he returned to the United States.

Many therapists still don’t recognize how race and culture can be intertwined with post-traumatic stress disorders, Ms. Rauch said.

“Post-traumatic stress doesn’t occur in a bubble,” Ms. Rauch said. “If it occurs to someone who is going through cultural issues or who has certain beliefs, it can have a big impact.”

Mr. Caro has found refuge in his unquenchable thirst for knowledge and self-understanding. He reads constantly — large volumes on philosophy, religion, and morality. Subjects are as varied as war, peace, and cultural studies. It’s a form of meditation for him.

He continues his therapy and has finally found the peace that eluded him for so long.

“I think I’ve made some peace with myself,” Mr. Caro said.

“I do wish I had that Purple Heart back. It was an acknowledgment of who I was and how I felt then. But I look at things differently now and those were choices I made then.

“If anything, Vietnam forced me to look deep into my soul to find purpose and meaning.”

Avoiding stereotypes

Shedrick Williams, 50, of Toledo wishes his therapist would have believed more of what he said.

“I told my therapist that I was having violent thoughts, I couldn’t sleep at night,” Mr. Williams, a retired U.S. Air Force staff sergeant, recalled trying to tell his therapist after he was discharged from the military 11 years ago.

“He told me I didn’t have post-traumatic stress; it was just my mind and body trying to get reacclimated to my old neighborhood.”

Mr. Williams, who is an African-American, told the therapist: “I didn’t have no high blood pressure before I joined the military. I didn’t drink or smoke before I joined the military. I didn’t own no guns before the military.

“I grew up in Toledo’s north side. I saw some traumatic things. Those were normal for me. So they blame it on the environment.”

Ms. Rauch said therapists do need to be careful and make sure their “own beliefs and stereotypes” don’t interfere with treating patients.

“Unfortunately, we’re not always perfect either,” she said.

Contact Federico Martinez at: fmartinez@theblade.com or 419-724-6154.