Setting the standard: Harriet Lane Handbook

For 50 years, this book has been a bible for hospital pediatrics

8/11/2014

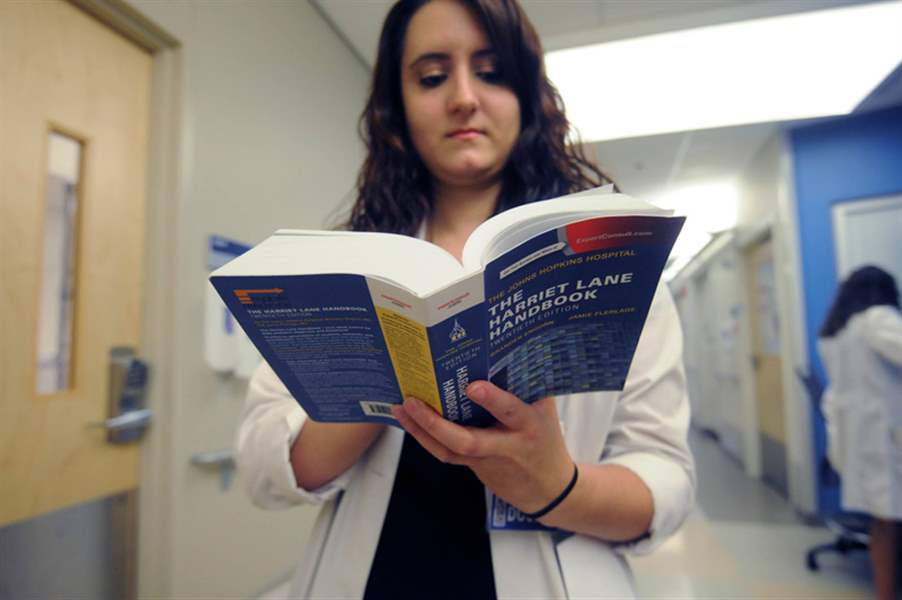

Dr. Emily Krennerich holds a 20th edition copy of 'The Harriet Lane Handbook' at the Johns Hopkins Children's Center in Baltimore.

BALTIMORE SUN

Dr. Emily Krennerich holds a 20th edition copy of 'The Harriet Lane Handbook' at the Johns Hopkins Children's Center in Baltimore.

In the early 1950s, six pediatric residents at Johns Hopkins Hospital sat down at a table and jotted down notes they thought would help as they began treating patients.

They made copies and put them in loose-leaf notebooks. Every few years, other residents would add information about tests, results, diagnoses and drugs for children.

Hopkins residents are still editing the Harriet Lane Handbook six decades later, but now the pearls of wisdom are professionally published and distributed so widely that they’ve been translated into more than a dozen languages. Dr. Branden Engorn, the chief resident at Hopkins in charge of the latest edition, said new doctors there still cling to copies.

“It was the kind of book that when you got yours, you wrote your name in black Sharpie on all corners,” he said. “If you put it down, you knew it was yours because there were so many floating around.”

He also said crops of trainees often could be identified by the color of their copies. Dr. Engorn had a pink one in medical school at Virginia Commonwealth University, and he got a green one when he began at Hopkins in 2009.

The latest edition is blue, but incoming residents might be better known by their smartphones. “The Lane,” as the book is known, now comes with an app.

Engorn said paper still rules with many doctors, and it’s common to see markings, notes and colored tabs pasted on important pages, such as those with blood pressure readings and medication dosages that change with height, weight and age.

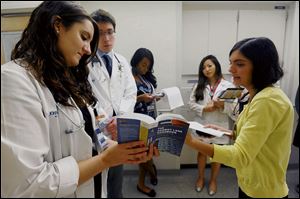

Dr. Emily Krennerich, left, and Tina Navidi refer to 'The Harriet Lane Handbook' as they make the rounds with medical students. Each doctor wrote a chapter in the 20th edition of the book.

In all, the book is now 1,132 pages, printed in type small enough to allow the paperback technically to fit into a lab coat pocket, though some residents say it’s a bit bulky for that.

Several doctors said there are now other popular references, largely online, but perhaps none as comprehensive and ubiquitous. And among the nonvirtual offerings, it’s one of the cheapest at $50.

Every three years, more than 100,000 copies are printed and distributed by Elsevier, a medical and scientific publisher, which makes the book one of its big sellers.

Jim Merritt, a senior content strategist at Elsevier, said it’s unusual for a medical publisher to take on a book edited by residents, though top Hopkins professors are consulted on each chapter. He said the publisher interferes little beyond controlling deadlines and chapter lengths.

“The fact that this book has reached its 20th edition tells you about the quality and performance over the years,” he said.

The book was named for Harriet Lane, who founded the nation’s first children’s clinic at Hopkins more than a century ago.

There’s no telling how many children’s lives it has saved or improved since then, said Dr. Robert Haslam, who edited the fourth version in 1965 while he was recovering from spinal surgery and in a cast. Elsevier agreed to publish the book after his edition.

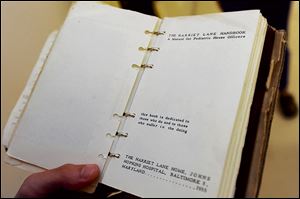

The dedication page of the 1955 edition of the handbook.

Haslam said he constantly referred to pages, including one concerning the metabolism of cortisone, the first treatment used for childhood leukemia, which at the time was nearly always fatal.

He also remembers local children coming to the hospital with such high lead-poisoning levels that they would be convulsing. A test was needed to confirm the diagnosis, and the doctors would use a recipe of chemicals found in the book to mix with the child’s urine.

“Everyone had their handbooks open,” he said. “If the urine turned green, we’d get them treatment for lead poisoning. ... The alternative was running to the library four blocks away and doing the test two or three hours later, which might have been too late.”

Haslam said some tests and treatments, like his lead protocol, have changed based on the most recent studies. His edition was truly pocket-sized at 242 pages, typed by a school secretary on 3.5-by-6-inch paper. It had charts and graphics, borrowed from textbooks with credit, such as those outlining electrocardiogram readings.

The book traveled with Haslam throughout a career as a pediatric neurologist that eventually took him to the University of Toronto, where he served as chairman of pediatrics, and the university-affiliated Hospital for Sick Children, where he was pediatrician in chief. Like many other hospitals in modern times, doctors there produced an institution-specific version.

Still, he said, newer editions of The Lane can be found there, as well as at top-rated U.S. medical schools and children’s hospitals.