Don't ask what David Lynch's 'Inland Empire' is about, just be mesmerized by the images

8/16/2007

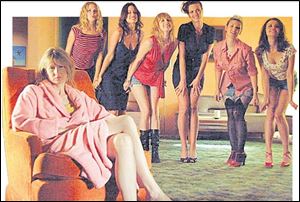

Laura Dern stars in Inland Empire, directed by David Lynch.

So one minute I'm looking at this family of humanoid rabbits gliding around a suburban home accompanied by a sitcom laugh track - the next minute, the cast (of human humans now) is doing a musical production number to "The Locomotion." OK, I'm officially lost. Then, I think, oh, Laura Dern. A foothold, finally. After a few haunting false starts, here we have our leading lady and she is playing an actress having an affair with her leading man - this is almost accessible.

But then a scene later she's playing a prostitute trudging across a highway packed with snow; and she has a bruise on her mouth; and she's sobbing; no, wait, she's southern; no, wait, she's crying again, not southern; and there's the snow again; now she's a housewife - in Poland?

Looking for what? Who?

Wait huh?

Exactly.

How do I get this across? Let's see. My first instinct is to offer you a road map to Inland Empire, the latest nonlinear rabbit hole of dream logic from David Lynch, new on video this week (Rhino, $29.98.) A good ole' art-house freak out (minus Bruce Dern, plus Laura), it may be the most willfully inscrutable movie ever released to a theater in this country, and that's counting the mid '90s films of Kevin Costner. Indeed, it was distributed last winter by Lynch himself and never received much of a wide release (and never opened in Toledo); and despite his Oscar nomination five years ago, this was not a shock. To say Inland Empire is not concerned with coherence is to say water is wet.

No, a road map is useless.

Then again, there is a real Inland Empire, and its location has a poetry not lost on Lynch. The title refers to the rural patch on the eastern edge of Los Angeles where the desert vistas never gave way to urban sprawl. There, Los Angeles is still feral, wild. Considering that the filmmaker's last work, 2001's Mulholland Drive, took its title from a road that slices Hollywood into halves, and Inland, like Mulholland, is preoccupied with splintered identities, let's just say he's pushing further into the unmapped territories of the subconscious.

If so, the legend reads:

"One mile = one identity."

Or something.

Like I could tell you what's going on here. Like anyone could for sure. But I can say, I was riveted - if nothing else, Inland Empire is a chilling experience. I was confused but never bored. If Lynch's 30-plus years of colonizing our collective imagination hasn't already done the trick for you, these three hours of exhausting avant-garde non sequitur and bizarro-world vignettes (shot on off-the-shelf, big-box-store digital video) will settle the difference. My best guess: the Inland Empire of the title refers to the unsettling landscape - in all its anxiety, fear, and vulnerability - we carry with us everywhere.

In short, Lynch's life work.

Since his feature debut, Eraserhead (1977), few American directors have worked as ceaselessly to project the images floating in his head the way Lynch has. That said, Laura Dern deserves an Oscar, Emmy, Grammy, and a 21 gun salute from the Psychiatrist Society of North America for bravely following him, one more time, into those shadows. If you found Naomi Watts' sudden split into two women in Mulholland confusing, run, don't walk, in the opposite direction of Inland Empire: The closest thing to a recognizable reality we get is in the first hour, when Nikki Grace (Dern) learns she landed a role in a new movie.

She meets her pretentious director (Jeremy Irons) and her caddish costar (Justin Theroux) and quickly unravels from there. They're making an overwrought southern Gothic with the soapy title of On High in Blue Tomorrows, and like Mulholland (which started life as a tossed-aside TV pilot), the work had been started and mysteriously abandoned. The previous stars died. People say the picture may be cursed. That's when Nikki seems to become her movie character and slip further through Lynch's kaleidoscopic looking glass - and becomes two, then three, then four different women. (I think.)

What does it mean? Ha!

I can say, in confidence, with each new character, Dern seems to open a new door, not cycling back on themes and plot lines so much as seeing them from fresh vantages. Each character introduces a new angle on a recurring image; each angle amplifies that sense of being unsettled. Watts lends her voice to one of the humanoid rabbits, incidentally; Lynch gets astonishingly beautiful images of decay and rot out of that no-budget digital camera. But on occasion it's useless to discuss a film as a film, and this is definitely one of those times. Questions such as "Did you like it?" become irrelevant. Symbolism? Let us not go there.

Two weeks ago, when Michelangelo Antonioni and Ingmar Bergman died, a number of critics noted these were filmmakers held with the reverence of visual artists. They were painters, whose pictures happened to move. This is Lynch, a cubist, an abstractionist, an absurdist - an explorer.

Contact Christopher Borrelli at: cborrelli@theblade.com

or 419-724-6117.