Sam Shepard rides again as Butch Cassidy in ‘Blackthorn’

10/12/2011

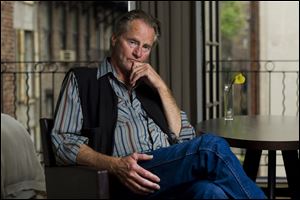

Actor Sam Shepard poses for a portrait in New York. Shepard portrays Butch Cassidy in the upcoming film, "Blackthorn."

NEW YORK — Sam Shepard is back in town.

For decades, he has migrated to New York from far-away country homes and life on the road. New York is the “arena” for his work: usually a play; sometimes a book; sometimes a movie.

“I’ve come and gone from this town so much, going back to ’63,” Shepard said in a recent interview over tea in SoHo. “It’s not the place I choose to live. It’s the place I choose to work.”

Shepard is now 67, his eyes are more sunken and his hair grayer, but he remains piercing, charming, and mysterious. The routine is remarkably the same. He drives his truck from his Kentucky horse ranch (he always drives, never flies) and returns to New York, where he first arrived as a 19-year-old actor from his father’s California farm.

He came, he says, “out of the desert” and soon thereafter set the theater world aflame with his visceral off-off-Broadway plays that hit the stage like pulsating jazz riffs.

The occasion for Shepard’s latest visit is the release of Blackthorn, a film that imagines Butch Cassidy (whom Shepard plays) had he lived on into old age in Bolivia. The role is fitting of Shepard: a solitary figure in exile.

Shepard, laughing hard, recalls an early critic remarking, "You don't look anything like Paul Newman!" A gritty and elegiac South American Western, Blackthorn bears little resemblance to the classic 1969 Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, which Shepard calls a "cartoon" in comparison.

Born on an Illinois army base, Shepard's father was a violent, alcoholic World War II bomber pilot who has informed much of the playwright's work. At the one production his father Sam Rogers attended, he loudly cursed his son's representation of family life.

Shepard got music from his father (Rogers was a Dixieland drummer, Shepard a drummer with the band Holy Modal Rounders, which toured on Bob Dylan's famed Rolling Thunder Revue) as well as struggles with alcoholism. In 2009, he was arrested for driving under the influence.

Shepard's "family plays" -- Tooth of the Crime, Curse of the Starving Class, the Pulitzer Prize-winning Buried Child, and True West -- make up some of his most well-regarded work.

Shepard lives with his longtime partner Jessica Lange, with whom he has two of his three children. But he's remained close with former girlfriend Patti Smith, musician and poet, and recently recorded several songs with her -- old tunes by Washington Phillips, Ivory Joe Hunter, Slim Harpo, and Richard Rabbit Brown.

Though Shepard often evokes the inscrutable American qualities so deeply imbedded in his writing, he's surprisingly generous during the course of a rambling interview. He's readily reflective and his humble conversation is punctuated by diversions on various passions, old and new: the songs of Hank Williams; Bob Dylan's storytelling; the French-Romanian playwright Eugene Ionesco; Gary Cooper; Crime and Punishment, and Don Quixote, which he's rereading now.

Shepard's latest play was last year's Ages of the Moon. Though he releases fewer works nowadays, he still writes prodigiously. He flips through the notebook by his side (he always first writes in a notebook, later moving to typewriter), evidencing pages of several working plays, songs, short stories, and "stuff kind of like prose poems, I don't know what to call it."

He's just finished "the bones" of a three-act play he expects to stage in about a year. Shepard earlier swore off longer works, but says this one came to him "and I accommodated it."

Do the demons of his youth still drive his work?

"There's nothing serene about it," he says, laughing. "Yeah, I would say that it did come from a fractured sensibility. And it's still fractured because of the state of things. I'm extremely grateful that I found writing, but it doesn't make it any more peaceful."

Shepard has crisscrossed art forms, moving from plays to fiction to acting and music. But for him, the lines still converge in the theater.

"I always felt like playwriting was the thread through all of it," he says. "Theater really when you think about it contains everything. It can contain film. Film can't contain theater. Music. Dance. Painting. Acting. It's the whole deal. And it's the most ancient. It goes back to the Druids. It was way pre-Christ. It's the form that I feel most at home in, because of that, because of its ability to usurp everything."