AN APPRECIATION

Remembering Harold Ramis: He always made me smile

2/26/2014

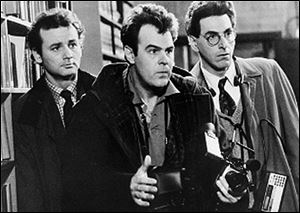

Bill Murray, left, Dan Aykroyd, center, and Harold Ramis, appear in a scene from the 1984 movie ‘Ghostbusters.’ Ramis died early Monday in Chicago from complications of autoimmune inflammatory disease, according to his attorney. He was 69.

What I will remember most about Harold Ramis is his smile — always there in his work, ever playing across his face. Even when the writer/ actor/ director was trying to look serious, his eyes twinkled and a grin tugged at the corners of his mouth. As if he couldn’t help it.

He carried humor with him everywhere, packed in his bag of writing tricks, packed in his 6-foot-2-inch frame. Ramis always seemed on the verge of laughing out loud, as if he’d just remembered a favorite joke.

That sense of amusement at all the ridiculous and silly curves this crazy life could throw a person saturated his work from the beginning. He started his career as a joke editor for Playboy, a job description that seems like a punch line.

That particular brand of nonsense was never more famously on display than in 1984’s Ghostbusters, which he co-wrote with Dan Aykroyd.

Ramis was never a traditional critic’s darling, but he was always entertaining. He would make you laugh. Even his last film, 2009’s Year One, a clumsy caveman comedy starring Jack Black and Michael Cera, still delivered sight gags. I dare you to look at Cera in animal skins and not giggle.

There is a certain symmetry that Ramis, who died at 69 on Monday, would spend his final days in Chicago. It was where he was born and where he would hone his comic sensibility as a member of Second City’s famous improv theater group, with its rich legacy as both a home and a launching pad for the talented and the funny. Second City would help push him from the improv stage into other mediums, starting with the cult comic hit SCTV.

For a time, Ramis was head writer of the TV show that specialized in parodying other shows. So it made perfect sense when Ramis began directing an occasional episode of NBC’s The Office, the last time in 2010. After that, he mostly faded from sight to fight the disease that would eventually take him.

It really couldn’t be more fitting that his movie breakthrough came as one of three writers of 1978’s National Lampoon’s Animal House, with its tawdry teasing of frat-boy culture and the power of outsiders to upend convention. Nearly everyone has a favorite scene; a certain mayor’s daughter being pushed along in a shopping cart is mine.

A long line of “loser” comedies continues the tradition to this day. And though a college campus might not be the setting each time, there are always lessons to be learned and mirth to be had at the expense of the staid.

Part of the filmmaker’s appeal is because Ramis was a populist at heart. Films such as Caddyshack, Groundhog Day, Multiplicity, Analyze This in 1999, and Analyze That in 2002 were easy to enjoy. Ramis’ wit was more of the Three Stooges variety; there wasn’t much of a mean streak.

Ramis understood that one of the most powerful common denominators among humans is the desire to laugh — especially at someone who actually fumbles and fails at life a lot like, but slightly more, than the rest of us. Ramis, working with great comedians who also happened to be friends — Chevy Chase, Bill Murray, Billy Crystal among them — helped keep physical comedy and the art of slapstick alive.

Though I’ve laughed and loved many of Ramis’ films — those he’s written, those he’s acted in, those he’s directed, and those in which he’s done all three — my personal favorite will always be 1993’s Groundhog Day, which he directed and wrote with Danny Rubin.

The notion of the ultimate romantic do-over, that a second or 50th chance to get it right might be possible, never fails to stop me as I channel surf for a late-night movie fix. Bill Murray is at his most charming — eventually — after starting the film as one of those obnoxious TV weathercasters certain he’s destined for more, not because he’s smarter but because he plays well on TV.

Inside all the silliness of piano lessons and drink ordering is one of those fundamental life lessons — that the secret to keeping love alive is in the listening. In Groundhog the sweetness is so central it extends far beyond Murray’s romancing his news producer Rita, played by Andie MacDowell, as hearts-and-flowers as all of that is.

For all the funny, it is a film filled with small acts of kindness, never funnier or more of a test than Stephen Tobolowsky’s annoying insurance salesman. When, after about the fourth time the scene is run, Ned finally makes the sale of a lifetime to Phil, a look of surprise mixed with satisfaction overtakes his face. Which is what happens to me when I think of Ramis. Even now as the tears well, a smile breaks through.

Thanks for the comic legacy you left, Mr. Ramis, for reminding us it’s never a bad idea to laugh at our own foibles. And perhaps, to live more like you seemed too, where no Groundhog Day do-overs are necessary.