Parents of Newtown victim search for answers

Scientist couple on mission to ID biomarkers for violence

7/14/2013

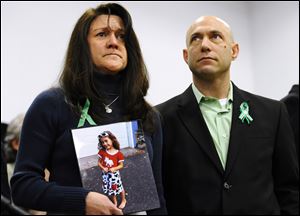

Jennifer Hensel, holding a portrait of her daughter, Sandy Hook School shooting victim Avielle Rose Richman, stands with her husband Jeremy Richman at a news conference at Edmond Town Hall in Newtown, Conn.

WASHINGTON — Families advocating for stricter gun laws have been a near-constant presence on Capitol Hill since the horrific school shooting six months ago in Newtown, Conn.

Jeremy Richman and his wife, Jennifer Hensel, favor gun control, too, but they are focused on other ways to reduce violence. Their mission is to prevent violence by finding biological indicators that predispose people to it.

It’s a logical move for them. Both are scientists — they met in a course called Recumbent Methods of DNA Technology at the University of Arizona — and that compels them to find answers.

They have a personal stake, too. Their daughter, Avielle, a curly-topped 6-year-old, was among those who were gunned down at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown along with 19 other children and six educators.

They refer to the shooting simply as “the 14th,” the date in December that Adam Lanza opened fire in their daughter’s first-grade classroom. They spend their days wondering whether there were clues in the killer’s physiological make-up — his DNA, his blood, his brain chemistry.

Again and again, they ask why. Not why their daughter, not why their school, not why their town. Rather, they want to know why science hasn’t yet identified the biological markers that make some people more likely to kill.

Discovering what leads to violent behavior ought to be no harder than discovering why high levels of cholesterol predispose people to heart disease, said Mr. Richman, a pharmaceutical researcher at Boehringer Ingelheim in Danbury, Conn.

There is no test that could predict every violent crime, but scientists say there are identifiable inherited traits linked to aggression that are worth exploring. Studying them could be the key to ensuring proper treatment and reducing violence.

Biomarkers are observable biological characteristics — such as genes, enzymes, hormones, or specific kinds of cells — that indicate a propensity for a physiological state. For example, high cholesterol is a biomarker for heart disease.

Mr. Richman and Ms. Hensel want to see more work on identifying biomarkers for violence. That’s why they created the Avielle Foundation in their daughter’s name. First they’ll raise awareness of the research possibilities, then they’ll raise and distribute grants to help pay for the work.

Biology isn’t enough to explain violence, Ms. Hensel said, but that doesn’t mean it isn’t worth studying.

Numerous conditions have both biological and environmental components, said Ms. Hensel, who has worked as a clinical microbiologist and now owns a medical and scientific communications company.

The next step is using the information to help people with biomarkers get the help they need. That means reducing the stigma of mental illness and focusing instead on what Ms. Hensel and her husband call “brain health.”

“I’m not looking for some moral rightness out of this. I’m looking to prevent further tragedies,” Mr. Richman said during a recent plane trip home from Washington, D.C., where he attended a White House conference on mental health.

On the tarmac at Ronald Reagan National Airport he thumbed through photos of Avielle on his cell phone. Among them is one of her looking at fireflies on a road trip to Iowa last summer to see relatives.

“We were seeing fireflies all over the place and Avie and I were in awe. It was this hugely magical thing. To kids, fireflies seem like such magic and wondrous little creatures. As an adult who can biochemically explain what bioluminescence is, it’s still magical and crazy amazing,” he said.

“I still believe there is magic in the world.”

That’s why The Avielle Foundation chose an image of a firefly for its logo, he explained.

Several federal agencies including the Institute for Justice and the National Institute for Mental Health already are involved in studies on the connection between physiological characteristics and the propensity for aggression.

Researchers have identified two types of emotional problems that put people at risk for aggression. One makes people hypersensitive to threats and therefore more likely to lash out, and the other involves a decreased capacity for empathy, said James Blair, chief of the National Institute for Mental Health’s unit on affective cognitive neuroscience and a member of The Avielle Foundation’s science advisory board.

Several other studies also are under way.

One enzyme already has been linked to violent behavior. Monamine oxidase A, the gene responsible for it, is commonly known as MAOA but it’s also been called “the warrior gene.” Everyone has it but in slightly different variations, one of which has been shown to correlate to aggressive behavior.

But plenty of meek people have the variation, and many without it have committed violent crime, said Lisa S. Parker, director of the University of Pittsburgh’s master’s program in bioethics.

“Genetics is, at most, a small part of the story,” Ms. Parker said.

Still, it can be useful to identify biomarkers in order to develop good treatments, she said.

Mr. Richman agrees.

“What we’re proposing isn’t an alternative to fixing gun laws and addressing what it means to be safe in our communities. We want both,” Mr. Richman said.

The Avielle Foundation's Web site can be found at AvielleFoundation.org.

The Block News Alliance consists of The Blade and the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Tracie Mauriello is Washington Bureau chief for the Post-Gazette.

Contact Tracie Mauriello at: tmauriello@post-gazette.com or 703-996-9292.