FREE SPEECH FOR THEE?

Is there a First Amendment case to save — or sink — net neutrality?

12/1/2017

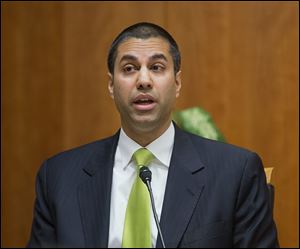

Ajit Pai, an appointee of the Trump administration who became the FCC’s chairman earlier this year, has made the repeal of the net neutrality rules the centerpiece of his tenure at the agency.

Getty Images

If you have used a computer in the past few weeks, odds are that you’ve encountered the phrase “net neutrality.” Net neutrality is a principle and a set of rules specifying, in effect, that internet service providers (ISPs) should treat all traffic on their networks equally.

According to the American Civil Liberties Union, “network neutrality means applying well-established ‘common carrier’ rules to the internet in order to preserve its freedom and openness,” where “common carriage prohibits the owner of a network that holds itself out to all-comers from discriminating against information by halting, slowing, or otherwise tampering with the transfer of any data (except for legitimate network management purposes such as easing congestion or blocking spam).”

This contentious topic has been one of the concerns to endure more than a few days in the whirlwind that is our current political climate, and in view of the importance of the internet in our lives, it is one that can be expected to remain a hot topic for the foreseeable future.

The idea of net neutrality was introduced in 2002 by legal scholar Tim Wu, who argued that no authority should be able to decide what kind of information was allowed or not allowed on the internet. The net neutrality rules, formally known as the Open Internet Order, were put into effect in 2015 by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), then operating under a majority appointed by President Obama.

Ajit Pai, an appointee of the Trump administration who became the FCC’s chairman earlier this year, has made the repeal of the net neutrality rules the centerpiece of his tenure at the agency. Mr. Pai contends that the rules impose “heavy-handed, utility-style regulations,” and that they have “depressed investment in building and expanding broadband networks and deterred innovation.” Mr. Pai says that he supports an “open internet,” but believes that less regulation is more beneficial to market growth.

Its proponents believe that the net neutrality rules keep information on the internet free and open, barring discriminatory practices and preventing ISPs from charging differently “by user, content, website, platform, application, type of attached equipment, or method of communication.”

If Mr. Pai’s proposal to repeal net neutrality is accepted, there will be no rules against paid prioritization of services, blocking websites, or similar activities. Supporters of net neutrality worry that a repeal of the rules will allow ISPs to charge users more to see certain types of content and create what are, in effect, fast lanes and slow lanes on the internet.

Under Mr. Pai’s proposal, ISPs would be able to manipulate their networks in two ways, through interconnection and “reasonable network management.” Which means that an ISP could create a separate lane for bandwidth-intensive streaming video from a company willing to pay for higher speed service. Or charge content providers higher rates for faster and/or more reliable interconnections, which is what happened to Netflix before the net neutrality rules were put in place (and is one of the reasons why Netflix opposes the repeal).

Supporters of net neutrality believe that the practices which follow its repeal will mark the end of the internet as we have known it. And it is of critical importance, they argue, because the internet plays a vital role in the day-to-day life of most American citizens, institutions, and organizations providing an environment in which we inform ourselves, learn, play, buy and sell things, and express our opinions about almost everything under the sun.

An interesting but not highly publicized aspect of the controversy surrounding the proposed repeal of the net neutrality rules is the question of whether there are First Amendment issues at work. At least one federal judge thinks so. (Advocacy groups and several U.S. Senators, including the embattled Sen. Al Franken, have argued lately that net neutrality is a First Amendment issue. While these arguments have emotional appeal, they lack legal foundation.)

In a petition for a rehearing en banc brought before the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia by the United States Telecom Association (USTelecom) and denied earlier this year, attorneys for USTelecom argued that the net neutrality rules are unfair because they prevent telecommunications companies and ISPs from regulating the content provided via their service. (Appellate courts in the U.S. occasionally grant rehearing en banc to reconsider a decision of a panel of the court in which the case concerns a matter of exceptional public importance or the panel’s decision appears to conflict with a prior decision of the court.)

If Mr. Pai’s proposal to repeal net neutrality is accepted, there will be no rules against paid prioritization of services, blocking websites, or similar activities.

Siding with the USTelecom in his dissenting opinion, Judge Brett Kavanaugh, considered by expert observers to be a possible future Supreme Court nominee, argued that the First Amendment rights of ISPs are violated by net neutrality regulations, citing the 1994 case of Turner Broadcasting System, Inc. vs. FCC, in which the Supreme Court found that “cable programmers and cable operators engage in and transmit speech, and they are entitled to the protection of the speech and press provisions of the First Amendment.”

The majority of Mr. Kavanaugh’s colleagues on the U.S. Court of Appeals held a different view, however.

They opined that comparisons between cable companies and ISPs cited by in Mr. Kavanaugh’s opinion were not valid. Chief among the reasons noted for this position is the fact that cable companies routinely advertise what programming they offer, whereas ISPs have generally advertised free and unfettered access to online content.

In addition, the majority opinion asserted that the Open Internet Order presents no First Amendment issues and noted that “the principle parties challenging the order in this court, who collectively represent virtually every broadband provider — including all of the major ISPs — bring no First Amendment challenge to the rule.”

However, the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals held that because the FCC labeled them “common carriers,” broadband providers lack the right to editorial control that accrues to newspapers and allows them to preclude content and/or advertisements. But the FCC has suggested that it may free broadband providers of common carrier obligations, which would presumably restore the legitimacy of broadband providers’ First Amendment challenge to net neutrality or other rules of similar character.

Read last week’s ‘Free Speech For Thee?’ column

The net neutrality rules will be repealed on Dec. 14. That much seems certain at this point. The rest of it is murky.

ISPs are promising to act fairly, and they argue that repeal will provide the incentive to invest more money in broadband capacity, ultimately making the internet better. Of at least equal importance, ISPs will have a choice in deciding whether to uphold the principles of net neutrality.

But only for the time being, because it is also likely that the repeal of the Open Internet Order will be litigated. Which is why the decision in the case of USTelecom versus the FCC, the opinions in the petition to rehear the case, and the promise to remove common carrier obligations may all be instructive as we look to 2018 and questions concerning both net neutrality and the First Amendment.

Contact Will Tomer at wtomer@theblade.com, 419-724-6404, or on Twitter @WillTomer.