Ex-Toledoan at center of storm in Florida investment scandal

2/4/2001

The Newgate Tower in Naples, once the headquarters of David Mobley's Maricopa Investment Funds, featured gold-leaf and Old Florida oil paintings. SEC receivers have auctioned the furnishings for $110,000 to help compensate victims.

UNK

PINE ISLAND, Fla. - David Mobley hobbles across the garage floor, wincing in pain with each step.

Wearing a sweat shirt, unshaven, and bleary eyed, he plops down on the rear of a car and peers out the door.

No one was supposed to know he was here - not the victims of his $100 million investment fraud and certainly not reporters. “Just go,” says the Toledo native, rubbing an injured leg.

Once a self-styled stock guru with expensive tastes and $120 million in his bank accounts, he now spends his days in a tiny bungalow on this scrubby island in the Gulf of Mexico.

Broke and alone, this is how life has turned out for the man who once hobnobbed with Florida Gov. Jeb Bush and publisher Steve Forbes.

No more $1 million homes in Florida and Colorado. No more Jaguars and Mercedes Benzes.

The world he created so carefully collapsed a year ago when it was revealed the millions of dollars he was supposedly investing for his clients was a fa ade: He was stealing their money and spending it, prosecutors say.

They contend more than 140 people lost close to $101 million in a scandal that has left some victims destitute.

More than a securities fraud case, he is also accused of bribing two local county commissioners in a real-estate venture that is now an ongoing political soap opera in southwest Florida.

Facing a fraud trial in June, the ex-Jeep-worker-turned-investment advisor now lives in exile on this isle off the coast of Fort Myers.

“How the mighty have fallen,” says car-dealer Mike Beaver, who lost $1 million in the scheme.

Just a year ago, the 44-year-old Mr. Mobley was living in a $1 million home in upscale Naples. The popular money manager and developer was emblematic of the booming 1990s, when day traders rode the bull market to enormous wealth.

Born in an inner-city home in Toledo, he moved to Naples in 1992 and became a noted investor in only a few years, earning his clients 61 percent on their investments, according to his claims.

He enjoyed $3,000 cigars and he spent weekends in his $1.7 million mountain chalet in Colorado, records state.

But after complaints by clients and an investigation by federal regulators last February, Mr. Mobley tearfully confessed: He had spent most of his clients' money to support a lavish lifestyle and failed business ventures.

One of his last acts before his collapse: paying himself a $2 million bonus, records state. Authorities have since taken the money back.

Prosecutors and victims also discovered his secret past: a personal bankruptcy amid bad-check and grand-theft charges in Toledo - crimes that left a dozen victims and made little news.

Now, after a year of headlines and investigations, Floridians are left to ponder the largest hedge fund collapse in state history, and one of the largest in the nation, says Larry West of the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission.

Some of the victims have lost their life savings, while others have been forced to sell their homes, cars, and in some cases return to work after retiring, according to their lawyers. At best, they can expect to recover about 20 cents on the dollar from what's left of the Mobley estate, victims' lawyers say.

Mr. Beaver, who lost $1 million, says he is waiting for the day he can confront Mr. Mobley. “My concern is that I may not be responsible for what I do,” he says. “This man has no conscience.”

And then there are those such as Sherry Smith, 59, a Naples retiree who lost $915,000.

“The trouble, the heartache, the stress - he caused us so many problems,” she says. “I may still have to sell my house. My friends have already sold theirs. What really blows my mind is that we really trusted this guy.”

Several charities in the Naples area have also found themselves in a moral dilemma: They are being asked by the government to return millions of dollars given to them by Mr. Mobley.

Charged with civil fraud by federal regulators last February, he has since been indicted here on 20 counts of federal criminal fraud and money laundering. He was released on a $75,000 bond in October over the objections of prosecutors - the bond pledged by his mother, Carolyn. If convicted of the most serious charges, he could spend the rest of his life in prison.

The graduate of Toledo's former Macomber Vocational High School says his side of the story has not been told. “It's all going to come out at my criminal trial,” he said during a brief interview at his bungalow. But given an opportunity to respond, he refuses.

It has been a year since the scandal broke - a financial disaster that stunned the upscale town of Naples like few other events. But even after the facts surfaced, people are still asking: How did this happen?

In the words of victims' lawyer Mark Raymond: “How did a guy from Ohio come in here and do so much damage?”

The Newgate Tower in Naples, once the headquarters of David Mobley's Maricopa Investment Funds, featured gold-leaf and Old Florida oil paintings. SEC receivers have auctioned the furnishings for $110,000 to help compensate victims.

At the age of 13, David Mobley was dreaming of success.

Raised in a working-class neighborhood surrounded by old factories, he once scribbled that he wanted to be a millionaire by the time he was 25. He even wrote his goal on a piece of paper and taped it to a wall in his home at Towbridge and Bishop streets.

His mother, Carolyn, a secretary at the Jobst Institute, was a major influence in his life, recalls Mr. Mobley's former sister-in-law, Barbara Buck. “She wanted him to do better, to rise above their surroundings. I'm sure that had something to do with his ambitions.”

The youngest of four siblings, Mr. Mobley “spent a lot of time alone,” Mrs. Buck said. As he was growing up, his father, James, a truck driver, was away for long periods, she recalled.

So young Mobley would spend hours at the downtown public library, devouring books about the lives “of successful business people,” he wrote in the forward of the 1998 book, Trading Your Way to Financial Freedom.

He wrote that he convinced his parents to open a brokerage account for him at a local Merrill Lynch office - the start of an obsession with stocks and bonds that would lead to his career in Florida.

In 1967, an event occurred that would shape his life: His brother Daniel was killed in Vietnam.

“I really think after that, the family babied David. They were worried about him and [doted] on him,” said his late brother's widow, Mrs. Buck.

He attended public schools and graduated from Macomber Vocational High School in 1974, with little recognition. Before he was 20, he married his first wife, Cathy Miller, and held several jobs, including an eight-month stint on the assembly line at Jeep in 1976.

He has claimed that he was a millionaire by 1981, but there's no indication he was earning seven figures.

In fact, he filed for personal bankruptcy in 1982, and lost four of the homes he was managing for his mother, says Evelyn Feiger, a longtime neighbor and family friend. “His mother was crushed,” recalled Mrs. Feiger.

By 1984, Mr. Mobley was divorced, with two young children. He tried selling fireplace inserts and white-walling tires, his former wife recalled. Bouncing from job to job, he was charged twice with writing bad checks, according to Toledo Municipal Court records.

By the late 1980s, he found a new calling: selling rural real estate. Farmers were undergoing rough economic times, and David Mobley saw an opportunity: By selling pieces of their land, they could keep most of what they had.

He began subdividing the properties and selling them, sharing the proceeds with the farmers. But he began to get into trouble.

Several people claimed he owed them money - including a couple who say he owed them $30,000 - leading to a lawsuit in Lucas County Common Pleas Court. About a third of the $30,000 was recovered.

Another man who attended Cornerstone Church with Mr. Mobley complained he lost $100,000 in a deal, according to Bob Bratton, now a chief deputy with the Ottawa County sheriff's office.

“He was beating people all over the place - contractors, workers - you name it,” recalled Deputy Bratton, then a Northwood detective.

Finally, one couple had enough. They said Mr. Mobley owed them $20,000 in a land deal.

“We finally filed a [criminal] complaint,” recalls Nancy Oberdick. “We were friends at one time; so it was hard. But we honestly thought that this would shock him into not hurting any more people.”

Shortly after Mr. Mobley moved to Naples, a Wood County grand jury indicted him on grand theft charges stemming from the deal. Charges were dropped after he agreed to make restitution.

“By then, I realized that he had been ripping off people, mostly from churches where he went,” said Deputy Bratton. “He was a con artist who hustled church groups. But this is where he learned his trade. Most of these people didn't want to press charges.

“We were just a training ground for him. He learned from us how to deal with the system. The groundwork was laid here. Now they got a monster down there [in Florida].”

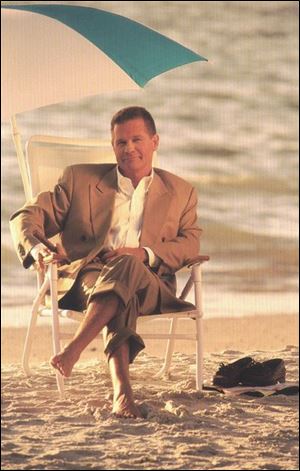

David Mobley enjoys a cigar on a beach in Naples. This promotional picture was used in his own Maricopa Investments Funds brochure, where he claims his investment results are among the highest of any hedge fund in America.

There were red flags everywhere if anyone had bothered to pay attention.

Soon after Mr. Mobley arrived in Naples, Detective Bratton called the local Collier County Sheriff's Office with a warning: Be careful of this guy. He's known for his financial scams and may have already set up shop there.

“I wanted to give them a heads up,” recalls Mr. Bratton, who officially noted his call on Jan. 7, 1992.

But Collier County sheriff's deputies never made a report, nor did they share their information with state regulators.

That same year, Mr. Mobley opened a financial-services firm.

With his second wife, Gwen, a Tiffin native, and his two children, he was anxious to start over. He joined a local church and charities like Quest for Kids - scholarships for the poor - and began to get invited to social events, say those who know him.

Records show he set up the Maricopa International Investment Corp. in 1992 - his first step toward his rise in the financial world.

He was quickly accepted into the Naples community, a friendly enclave of retirees and snowbirds - many from the Midwest.

“It's transient. It has a lot of people from other places, and no one really knows each other,” says attorney Mark Raymond. That kind of “new” community allows for “a lot of fast money and fast talkers,” he adds.

Though Mr. Mobley was acting as an investment adviser, no one bothered to check to see if he was legally authorized to trade in securities.

From 1993 to 2000, he advertised in the Naples area yellow pages as an investment adviser and securities dealer, but he never had a broker's license.

Though he established at least 20 securities and investment corporations under his name with the state of Florida, the state never checked to see if his companies were legally authorized to trade.

A spokeswoman with the division of securities said no such checks and balances are in place.

By 1994, he set up his company as an umbrella for a group of investor pools known as “hedge funds.” These are pools restricted to people with high net worth or incomes of more than $200,000 a year.

The funds are exempt from most disclosure laws - the perfect tool for someone who wants to avoid scrutiny. Relying on stock index options and Treasury debt futures, the funds are designed to earn money even when the market is down.

Mr. Mobley did not disappoint. He began to post earnings of more than 50 percent, even after he took out his 30 percent fees.

“I admit I was impressed,” says Ms. Smith, a victim. “A lot of people felt he was so good at what he was doing.” More people began to flock to the soft-spoken guru with the boyish looks and savvy market skills.

But there was always something missing from his hedge fund reports: audited statements.

Every month, investors would get monthly reports from Mobley's Maricopa Funds, but none of them was inspected by a third party.

Most hedge funds are audited, but Mr. Mobley told investors he did not want his funds scrutinized because outsiders would learn his trading strategies - rare secrets that were making people fortunes, say victim lawyers. Money poured into his funds - $120 million by 1998, court records show.

Because of his ties to Quest for Kids, he began to rub shoulders with national figures who would speak at Quest conferences. He had his picture taken with Barbara Bush, Norman Schwartzkopf, among others, and hung them on his office wall.

Now a recognized player in town, he began to schmooze with Collier County commissioners such as John Norris and Tim Constantine, a rising star in the local GOP. He started a cigar bar known as Heaven and moved his offices into the penthouse of the Newgate Tower, with a sweeping view of the Gulf of Mexico.

By 1997, he entered the Florida real-estate world by proposing one of the most unique golf courses ever unveiled in Florida: Stadium Naples. The $100 million plan called for luxury homes surrounding a championship course with a 15,000-seat stadium at the 18th green for tournaments.

At least nine times, County Commissioners Norris and Constantine cast favorable votes on the project and another development founded by Mr. Mobley, according to the Collier County state attorney's office.

SEC receivers catalog the cigars from Mr. Mobley's cigar bar. Some 85-year-old cigars once sold for $3,000 apiece, but the entire 5,000 inventory was sold for $7,000.

To his clients, he was a hero, but to some outsiders, Mr. Mobley's claims were too excessive to ignore. In its worst year, Maricopa showed 34 percent returns, and in its best year 61 percent, with no losses in its 88-month history.

By the time Barron's financial magazine began to ask questions, it was too late for damage control.

The magazine dug up Mr. Mobley's personal bankruptcy and his criminal record. They even questioned his investment claims.

An article on Feb. 12, 2000, spurred an investigation by the SEC and in an emotional confession days later, he admitted to diverting his clients' money to his own use, and faking investment returns, according to affidavits.

In all, about $60 million was spent on his own lifestyle and failed business ventures, including $3.4 million on Stadium Naples. He paid himself a $1 million annual salary, bought a Jaguar, a Mercedes Benz, and a $1.7 million chalet near Vail, Colo., with $300,000 in furnishings.

In the wake of the collapse, much has happened that shows the extent of Mr. Mobley's actions over the past eight years:

Mr. Norris is accused of accepting a secret ownership stake in Stadium Naples worth $8 million at one time, says the state attorney's office, as a reward for his official actions on behalf of the development.

Mr. Constantine, the youngest person ever elected to the Collier commission and a future congressional hopeful, is accused of accepting a $100,000 loan from a Mobley company that was later forgiven.

Mr. Mobley wrote a letter to the judge overseeing the collections, complaining that items in the cigar bar should have sold for more, including 85-year-old cigars that he says were selling for $3,000 apiece. Items from his penthouse office sold for $110,000, including artwork and furniture.

A broke David Mobley lives in this rented bungalow on Pine Island, Fla., a place once famous for pirates. Mr. Mobley used to live in million-dollar houses in Naples, Fla., and Colorado.

Sixty miles from his enemies, Mr. Mobley lives on an island once known for pirates, Calusa Indians, and moonshiners. Covered by pines, swamp cabbage, and funky wood homes on stilts, the 17-mile-long island has been known as a “poor man's Palm Beach.”

Far from his creditors, he rents a small, “Cracker Home,” or concrete, block house (925 square feet) at the southern end. His neighbors say they rarely see him, and recently, a leg injury has caused him to limp.

He avoids nearby restaurants, opting to patronize two convenience stores where he is known for buying beer.

“He comes by sometimes three to four times a week. He always buys the cheap beers, like Old Milwaukee,” said Jan, the night clerk at the Circle K store.

On a recent cool, sun-splashed morning, he hopped on one leg to the garage door, grimacing. At first, he refused to talk, but moments later, simply said, “There are a lot of things I would like to say.”

Asked if he was sorry for what he had confessed to a year ago, he said he will respond at his trial.

“This will all come out at my criminal trial. I care very much about what has happened.”

He has at least one supporter in his mother, who moved to Naples to be close to her son. “He's my son, and I absolutely stand by him,” she said, her voice cracking. “I lost a son in Vietnam. ... We're a loving, caring family.”

Several lawyers involved in the case say they are surprised he is willing to go to trial, considering he has already admitted the scams to the SEC and has pledged to help the receiver recover assets. His lawyer, assistant federal public defender Martin DerOvanesian, could not be reached.

Chris Vernon, a lawyer representing victims, says he believes that Mr. Mobley was trying to recover losses by branching out into real estate and other ventures. “He was always looking for one, big hit,” says Mr. Vernon. “He knew he was using their money, and he was trying to make it up in real estate. Maybe he would be able to repay them before they knew.”

Sherry Smith says she just hopes she recovers some money from the man who “was so smooth.

“I still remember how he would always greet me with a peck on the cheek, and a hug, and tell me how well I was doing.”

Mike Beaver, who lost $1 million, says he decided to purchase one of Mr. Mobley's desks for $4,000 at an auction last year.

“I got the credenza, the desk, and the chair,” he declares. “And the next thing I'm going to get is him.”