Detainee served as imam at prison

2/23/2006

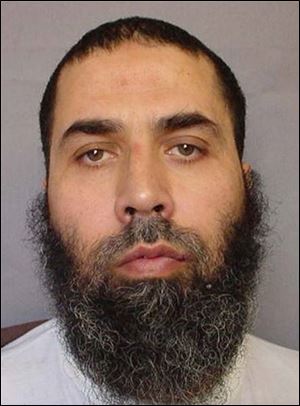

El-Hindi

A year before he is accused of plotting to attack American soldiers in Iraq, Marwan Othman El-Hindi offered spiritual nourishment to Muslim prisoners at the Toledo Correctional Institution as an "imam," or religious leader.

Khelleh Konteh, the warden, said he walked Mr. El-Hindi out of the North Toledo prison for good on Dec. 30, 2003, after seeing the native of Jordan give an inmate contraband bread and oranges instead of lessons from the Qur'an, the Islamic holy book.

Prison employees are forbidden from slipping food to prisoners, who receive three square meals a day, the warden said.

"I was focused on the safety of the prison," Mr. Konteh said. "If he was going to do that, what else was he going to do?"

Mr. El-Hindi, who turns 43 today, did significantly more than lead prayer services, according to a federal indictment issued Tuesday against him and two other Toledo-area residents.

The indictment alleges he studied how to build suicide-bomb vests and "improvised explosive devices" or IEDs, a popular weapon among insurgents inside Iraq.

An instructional video similar to what Mr. El-Hindi would have viewed is available at www.globalthreat.com. It shows the assembly and detonation of a thin vest filled with enough firepower to kill or injure dozens of people standing near the bomber.

Mr. El-Hindi approached an accountant in Dearborn, Mich., to establish a nonprofit organization that would divert government grants for "tax education services" to jihadist paramilitaries, the indictment charges.

He also asked a former soldier, identified in the indictment as "the Trainer," to provide him and his fellow conspirators, Mohammad Zaki Amawi, 26, of Toledo, and Wassim Mazloum, 24, of Sylvania, with security and bodyguard training.

Starting in November, 2004, the Trainer secretly passed on the group's conversations and activities to law-enforcement officials. The insider's efforts stopped Mr. Amawi from smuggling five laptop computers into Jordan in August.

Local Muslims, who the government considers to be the collateral victims of these three individuals' alleged crimes, assisted the investigation by telling authorities about Mr. Amawi's "radical" comments.

"It's very important that the community work with law enforcement to weed out the bad apples," said Craig Morford, an assistant U.S. attorney in Cleveland.

Proselytizing at a prison would have fit within the indictment's pattern of terrorist preparations, according to Senate committee testimony by FBI Director Robert Mueller last year.

"Prisons continue to be fertile ground for extremists who exploit both a prisoner's conversion to Islam while still in prison, as well as their socioeconomic status and placement in the community upon their release," he said.

Despite such concerns, Warden Konteh said federal agents never contacted the Toledo Correctional Institute about Mr. El-Hindi's role there.

"This was all news to us," Mr. Konteh told The Blade.

Richard Kerger, an attorney for Mr. El-Hindi, said his client's stint as a Muslim prison cleric might be unrelated to the indictment's charges.

"I know a lawyer who got in trouble for smuggling a cheeseburger for this guy," he said. "They caught him because of the odor. He didn't recruit any terrorists.

"Don't rush to judgment," Mr. Kerger added. "There's this wonderful tendency in the United States to convict someone upon indictment, particularly when there's a heinous crime: terrorism."

Married three times and the father of seven children, Mr. El-Hindi, the eldest of the three indicted men, appears to be somewhat of a mystery man.

Filings with the Illinois Secretary of State show that a "Marwan El Hindi" registered a company in Chicago called Royal International in 1997. His residence is listed as a white-brick house in suburban Oak Lawn, Ill.

During the 10 months of planning, the indictment states Mr. El-Hindi indicated that he wanted to teach two Chicagoans how to use suicide-bomb vests.

Mr. Kerger said he has not yet had the chance to discuss Royal International with his client, who along with Mr. Mazloum faces a detention hearing tomorrow.

"As far as we know, he wasn't involved with that business," Mr. Kerger said.

The imam at the Toledo Correctional Institution, Kamal Najib, hired Mr. El-Hindi to fill in for his role at the prison in a subcontract arrangement of sorts in September, 2003.

"Sometimes the one that was contracted cannot make it, and they send someone else," Mr. Konteh said. "He was just substituting for Najib."

A vocal opponent of the death penalty, Mr. Najib, whose original name was Wayne Palmer, is the son of the late Wayman Palmer, Toledo's director of community development in the 1970s and 1980s and a man for whom a YMCA branch in Toledo is named.

Paid $14,300 a year for his imam role at the prison, Mr. Najib is "exceptional," Mr. Konteh said.

As a 17-year-old, Mr. Najib was charged with robbing a carryout store and a supermarket with a concealed weapon. Sometime after discovering Islam, he was convicted of defrauding insurance companies.

Neither incident precluded him from working at the prison, Mr. Konteh said.

Before approving him to work, the Toledo prison ran a background check on Mr. El-Hindi with federal and state criminal databases, Mr. Konteh said. His record was clean, enabling him to become an imam.

There are no set standards within Islam for becoming an imam, said Ziad Hummos, president of the Masjid Saad, a West Toledo mosque.

Imams generally have at least a bachelor's degree from an Islamic university, and are authorities on the Qur'an, a text many imams memorize. Mr. Hummos was unaware that Mr. El-Hindi had these unique credentials.

Even without a governing board that oversees imams, an unqualified person would quickly be found out and discredited, Mr. Hummos said.

"You can call yourself a priest, or a pope," he said. "David Koresh called himself a prophet."

When he did come to services at Masjid Saad, Mr. El-Hindi kept himself "isolated" from most of the regulars because Muslims place a high priority on family values and he was seeking a divorce, Mr. Hummos said.

Mr. El-Hindi married his third wife, Marwa Aboud, in May. After his business closed in Syracuse, N.Y., he moved to Michigan and later Toledo, where he was self-employed and made $1,200 a month.

He faces unrelated traffic charges for driving without a license and ignoring a stop sign. He was convicted of a misdemeanor in 2003 for not taking care of his then residence on 423 White St. in East Toledo.

Oregon police arrested Mr. El-Hindi in 2001 for receiving stolen boxes of Tylenol, Motrin, a pain reliever, and Monistat 3, a cream that treats yeast infections, worth a combined $196.

Joan Elaine Palacio, whose 2002 murder remains unsolved, shoplifted the over-the-counter medicine from a Krogers grocery store in Oregon and dumped the items in the backseat of Mr. El-Hindi's white sedan.

When questioned by police, Ms. Palacio said Mr. El-Hindi was not her accomplice. No charges were filed against Mr. El-Hindi.

Mr. Kerger drew a parallel between the 2001 arrest report and the terrorism charges now pending against his client.

"It just shows that mistakes can be made," he said.

Blade staff writers Christina Hall, Mike Wilkinson, and David Yonke contributed to this report.

Contact Joshua Boak at:

jboak@theblade.com

or 419-724-6728.