GLASS CITY ALGAE THREAT ECLIPSED

Flint sets a new low for hazardous water

Residents furious after years of neglect

1/24/2016

Darryl Matiere, Sr., an Army sergeant and National Guard member from 1983 to 1992, denounces Michigan Gov. Rick Snyder to fellow Flint resident Audrea Crawford, not pictured. The two went to a fire station to pick up a case of bottled water on Wednesday.

THE BLADE/KATIE RAUSCH

Buy This Image

UAW Local 651 members, from left, Tedd Sain, Ken Davenport, Tony Jackson, Allen Jupree, and Anita Brown help unload a truck full of bottled water at Hasselbring Park Senior Community Center on Flint’s north side. The center sees near-daily shipments of water because of this two-year crisis.

Darryl Matiere, Sr., an Army sergeant and National Guard member from 1983 to 1992, denounces Michigan Gov. Rick Snyder to fellow Flint resident Audrea Crawford, not pictured. The two went to a fire station to pick up a case of bottled water on Wednesday.

FLINT, Mich. — Weakened by years of neglect, notoriously down-and-out Flint has blown past Toledo as America’s new poster child for water pollution.

That’s evident in the worry in the eyes of Flint’s 100,000 residents, a hardy bunch who — like Toledo — come from a city steeped in automotive history and union pride.

But unlike Toledo, where nearly 500,000 residents had to avoid algae-infested water the first weekend of August, 2014, Flint’s residents have been exposed to a much worse poison — lead — for nearly two years.

RELATED CONTENT: Lead-based paint still poses risk for families in Toledo

The city shown in ruins on the big screen in 1989, when Michael Moore chronicled his hometown’s deterioration in his award-winning documentary Roger & Me, is having its mettle put to the test like few, if any, U.S. cities in modern history.

Nobody knows when their water will be safe to drink again.

They’re told to put their faith in water filters distributed by the Michigan National Guard until something better happens.

Experts know the damage has been done and the best long-term solution is a complete overhaul of Flint’s underground distribution pipes and those throughout every house — a project that would cost untold billions of dollars.

Next week, the Michigan Legislature is being asked to provide $28 million more in relief aid, mostly to buy more faucet filters and bottled water. President Obama’s pledge to commit an additional $80 million in aid next week also is seen by many people as a proverbial drop in the bucket.

Toledo blew past Charleston, W.Va., where a chemical spill into the Elk River fouled water for 300,000 residents in January, 2014. Two decades before that, tap water was fouled for weeks in Milwaukee, where a 1993 outbreak of the parasite cryptosporidium killed 69 people and sickened more than 400,000.

IN PICTURES: The Flint water crisis

The sad irony is the crises in Milwaukee, Toledo, and Flint occurred in the water-rich Great Lakes region, often perceived as the last place where access or quality should be an issue.

“Every one of these water crises — Charleston, Toledo, and Flint — are unique. But the common thread is we’ve been taking our great water system for granted in this country,” said Peter Gleick, president and co-founder of the Pacific Institute in Oakland, Calif., which tracks global water stresses and publishes an inventory of the world’s water hot spots every two years.

“It’s inexcusable anywhere, but it’s especially inexcusable in a country that could have afforded to solve this problem a long time ago,” Mr. Gleick said. “We’ve taken it for granted forever that we’ll turn on our taps and high quality water will come out. We can’t assume that will happen all by itself.”

How it began

Flint Mayor Karen Weaver points out her city’s water crisis began nearly two years ago but fell on deaf ears for a long time even after poor and largely disenfranchised residents showed up screaming at public meetings with jugs of brownish-orange water drawn from their faucets.

By any measure, Flint’s water crisis has erupted into a national story with huge ramifications for the 2016 presidential election.

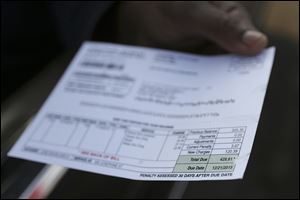

Flint resident Audrea Crawford says her December city water bill of $428.81 is too high for water that she really cannot use. Several people said they are charged in excess of $200 a month.

The story caught fire in the fall of 2015 after Dr. Mona Hanna-Attisha, director of the pediatric program at the Hurley Medical Center in Flint, and Virginia Tech’s Marc Edwards, an expert on municipal water quality, came up with hard scientific evidence that high-level Michigan Department of Environmental Quality and U.S. Environmental Protection Agency bureaucrats — despite their best efforts at soft-pedaling the crisis — couldn’t deny.

Michigan DEQ Director Dan Wyant and his chief spokesman, Brad Wurfel, resigned Dec. 29. Gov. Rick Snyder apologized that day and during his State of the State address Tuesday.

On Thursday, the U.S. EPA’s Midwest regional chief, Susan Hedman, accused of suppressing a federal EPA employee familiar with the Flint crisis, announced she would step down Feb. 1.

On Friday, the U.S. EPA blamed the state of Michigan and the city of Flint for responses that “have been inadequate to protect public health.”

Citing “serious, ongoing concerns with delays, lack of adequate transparency, and capacity to safely manage the drinking water system,” the federal EPA vowed to begin publishing sampling results on its website. It announced it has instituted, effective immediately, a new policy for staff members to report serious public health issues to their supervisors.

Scandal’s effects

Dr. Hanna-Attisha said she “was naive and at first didn’t believe it” when the scandal broke.

Her office holds records of blood drawn from most Flint children for routine lead tests between the ages of 1 and 2. Documenting the trend, she said, was the “easiest research project I ever did” because it only required about two weeks of analyzing records.

She and Mr. Edwards were initially called hysterical, said Dr. Hanna-Attisha, who said much of the criticism came from the Michigan DEQ.

What gnaws at her is how 8,000 to 9,000 Flint children aged 6 or under — nearly a tenth of the city’s population — are at high risk for brain damage and a number of other neurological, growth-impairing maladies associated with lead poisoning.

Most come from poor families who already face an uphill battle for a decent life, Dr. Hanna-Attisha said. Almost 57 percent of Flint is African-American. With 40 percent of city residents living below the poverty line, it is one of America’s poorest cities.

She said many of those children likely will never develop into the adults they could have been.

“There is no safe level of lead,” Dr. Hanna-Attisha said.

She cited studies that link the metal to lower IQs, impaired motor skills, attention deficit disorder, behavioral problems, hyperactivity, and even criminality as an adult.

Research also shows it can cause DNA changes that get passed on to future generations.

“All of the evils of lead are well-documented,” Dr. Hanna-Attisha said. “These kids have every obstacle in the world in front of them. Now, they have lead poisoning, too.”

Dr. Mona Hanna-Attisha, director of the pediatric program at the Hurley Medical Center in Flint, helped expose how local children were exposed to lead leaching into their tap water. She said she and other researchers will track many of Flint’s most at-risk kids for at least the next 20 years.

There is no known antidote. The best Dr. Hanna-Attisha said she can do is reassure young mothers “with that fear and that anguish and that panic and that trauma in her eyes” that not every child metabolizes lead the same.

Putting at-risk children on diets high in iron, calcium, and vitamin C can help absorb some of the lead. But that’s a long shot at full recovery, she said.

“If you could think of something to put into a population to keep them down now and forever, it is lead. It is the most damning thing you could do,” Dr. Hanna-Attisha said. “That’s why this is such an emergency and it’s been an emergency for almost two years. We’ve exposed an entire population to this neurotoxin and what is going to be the impact in five years, in 10 years, and in 20 years? What is going to be the impact on our education system, our mental health system, and our criminal justice system?”

Flint’s children

Late Wednesday afternoon, a CNN crew traveling with the cable network’s chief medical correspondent, Dr. Sanjay Gupta, was packing up its gear in another room as two more journalists were brought into Dr. Hanna-Attisha’s office for what has become a steady string of daily interviews.

Dr. Hanna-Attisha took a quick call from the Rev. Jesse Jackson as her guests were being seated.

She emphatically told the Rev. Jackson she can’t leave Flint to meet him in Chicago anytime soon and — surprisingly — implored him not to send more cases of bottled water.

“We don’t need more water. We need people to invest in these kids,” Dr. Hanna-Attisha said and directed him to a website flintkids.org, which is making plans to support kids victimized by lead poisoning.

During her interview with The Blade, Dr. Hanna-Attisha said she and other researchers will be tracking many of Flint’s most at-risk kids for at least the next 20 years.

Anita Brown, former investigator for Flint’s ombudsman, left, listens to former boss Brenda Purifoy speak about Flint’s challenges since an emergency manager was appointed in 2013.

“We need to do good for these kids,” Dr. Hanna-Attisha said. “These kids did nothing wrong.”

The following afternoon, Dr. Gupta reported on national television he’d found exposure levels among Flint’s most vulnerable age group “off the charts.”

Though health officials agree there is no safe level of lead, they generally agree the threshold for it should be no higher than 5 parts per billion, he said.

One Flint child, according to Dr. Gupta, had a blood-poisoning level of 13,000 ppb.

“It’s among the highest I’ve ever seen in the world,” Dr. Gupta said during his segment.

Political decisions

The birthplace of General Motors, Flint has seen its urban decay greatly exacerbated by the automaker’s decision to shut down factories there years ago.

But GM’s decision to abandon Flint is only part of the crippling domino effect: In 2013, Flint was one of five Michigan cities Gov. Snyder put under control of an all-powerful, state-appointed emergency operations manager to avert what appeared to be looming bankruptcies.

Many of the decision-making powers vested in local elected officials were, under Michigan law, transferred to emergency operations managers. In theory, that cuts down political stalemates and streamlines efforts to help cities regain fiscal strength.

The emergency operations manager at the time used his political clout to have Flint break ties with Detroit.

Detroit had been supplying Flint treated Lake Huron water for decades but at much higher costs than what Detroit residents pay.

Flint began making plans to eventually treat its own Lake Huron water. Its decision to draw from the Flint River, known for a legacy of corrosive automotive chemicals, was seen as a short-term fix to fill a three-year window.

The biggest mistake, said Virginia Tech’s Mr. Edwards, was the emergency operation manager’s decision to save a mere $100 a day by not having Flint treat the tap water with corrosion-inhibitors, a standard practice at all municipal treatment plants.

That allowed pipes to corrode and leach lead as well as other contaminants.

Flint became the only known U.S. city to skip that vital treatment process — an oddity Dr. Hanna-Attisha said inspired her to begin checking medical records on file for Flint kids after she was tipped off about the decision by a high school friend who works at the U.S. EPA’s headquarters.

The American Water Works Association, the Washington trade group representing the nation’s water-treatment plant operators, said in a statement last week that switching over to a new water supply always carries a big risk because of the complexity of water chemistry.

Many of the health effects in children are likely to take three to five years to develop.

But the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services said in a recent statement that Genesee County had a spike in Legionnaires’ disease — a bacterial infection that causes a severe type of pneumonia transmitted through inhaled water — in the summer of 2014 and 2015.

Of 87 known cases afflicting residents aged 26 to 94, 10 resulted in death.

Mr. Edwards said the whole Flint mess might have been avoided if that standard corrosion-inhibitor protocol had been followed.

Records show the Michigan DEQ and the U.S. EPA knew about the situation, but did not act.

“All of the leaks, the lead, and quite possibly the Legionnaires’ disease could have been avoided,” Mr. Edwards said. “I don’t think initially they did it to save money. I think they forgot.”

Loss of faith

In the aftermath of Toledo’s 2014 water crisis, then-Mayor D. Michael Collins told The Blade that algal toxins did far more than pollute the city’s water when they breached the aging Collins Park Water Treatment Plant and made their way into the metro area’s water supply.

He said Toledo’s event became a “crisis of confidence” in governmental officials.

That theme resonates strongly from the rough-and-tumble streets on Flint’s north side to Mr. Edwards’ office, a 13-hour drive way.

“We’re in this problem — it’s a man-made problem — because we weren’t told the truth,” Genesee County Sheriff Robert Pickell said.

His deputies helped the National Guard, the American Red Cross, and others distribute home water filters and cases of bottled water from a Flint fire station door-to-door.

“People lied to us,” the sheriff said. “People have lost faith in the capacity of government to work with them.”

Lt. Col. Ray Stemitz said he and other guardsmen “truly empathize with all of the residents of Flint.”

Flint began receiving treated water from Detroit in October again, yet what came out of their faucets continued to be discolored for weeks.

“It’s still brown, but I’d say it’s a little orange, too,” Drew Williams, 30, of Ridgeway Avenue said.

He said he worries about his 4-year-old daughter, Kiera.

At the Hasselbring Park Senior Community Center on Flint’s north side, Tobias Lee, 66, questioned why impoverished Flint residents are expected to pay for contaminated, unfiltered water they used.

One woman at Fire Station No. 3 on Martin Luther King Avenue showed a $385 bill she received for water usage. Several people interviewed said they are charged in excess of $200 a month.

Trina McNeil, 43, worries about her children, Niko, 18, and Dayvion, 14. She compared Flint’s situation to that of New Orleans in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina in 2005.

“Sorry is not going to fix the pipes,” Ms. McNeil said of Gov. Snyder’s apology. “The city of Flint is pissed off right now.”

Meanwhile, the leader of a Flint independent film-making group called Team 810 Productions said he has been using some of the group’s proceeds to help distribute cases of bottled water to city residents for weeks.

Yusuf Bauswell, 43, spent seven years in the Michigan Department of Corrections on charges of uttering and publishing, robbery, and failure to pay child support.

He said Team 810 is able to get bottled water to unconventional residents, such as the city’s homeless or those who don’t want a National Guard or police vehicle coming to their front door.

Residents together

James Arnold, 44, a Hasselbring volunteer and Flint native who works at GM’s Toledo Transmission Plant, said residents have felt disenfranchised for years but especially since Gov. Snyder put fiscal decisions under the control of emergency managers.

“We were already devastated. It didn’t start with the water. The water was the coup de grace,” said Brenda Purifoy, a Mount Morris Township resident who was the city’s last paid ombudsman until her position was eliminated with the appointment of the first emergency manager on Dec. 2, 2011.

Anita Brown, 50, Ms. Purifoy’s former chief investigator, said the ombudsman’s office gave Flint residents “an avenue to vent.”

Surprisingly, though, it’s bad water that’s bringing residents together, Ms. Purifoy said.

Darryl Matiere, Sr., 52, an Army sergeant and National Guard member from 1983 to 1992, called Gov. Snyder a “coward” and the situation “pitiful.” But he agreed the water crisis has formed a bond among Flint residents.

“We have come together standing as one,” he said.

Corrin Nelson, 38, said she worries about her three children. Her 3-year-old son, Kaesey, has autism.

A Flint resident for 15 years, she said she might move back to her home state of Georgia.

LaWana Walker, 43, and Tychernises Butler, 39, said they have had patches of hair fall out of their scalps. They blame it on the water.

Sanai Miller, 40, said it’s offensive to learn what the government knew.

He worries about his 5-year-old boy, Messiah Simpkins.

“I don’t have no faith in our government,” he said. “They can hand out all of the water they want, but they’ve got to fix the pipes.”

More than 500 lawsuits, including three class-action lawsuits, have been filed, according to news reports.

LaToya Jenkins, Hasselbring Park community center director, oversees near-daily shipments of donated bottled water and hears many of the frustrations.

She said Flint will endure “by the grace of God.”

“We’re just going through a storm right now,” Ms. Jenkins said. “Once the storm is over, the sun will shine. That’s how God works.”

Contact Tom Henry at: thenry@theblade.com, 419-724-6079, or via Twitter @ecowriterohio.