SPECIAL REPORT: NEGATIVE POLITICAL ADVERTISING

Voting spurs head games

Scientists study how, why mudslinging has become such an election-year staple

5/16/2016

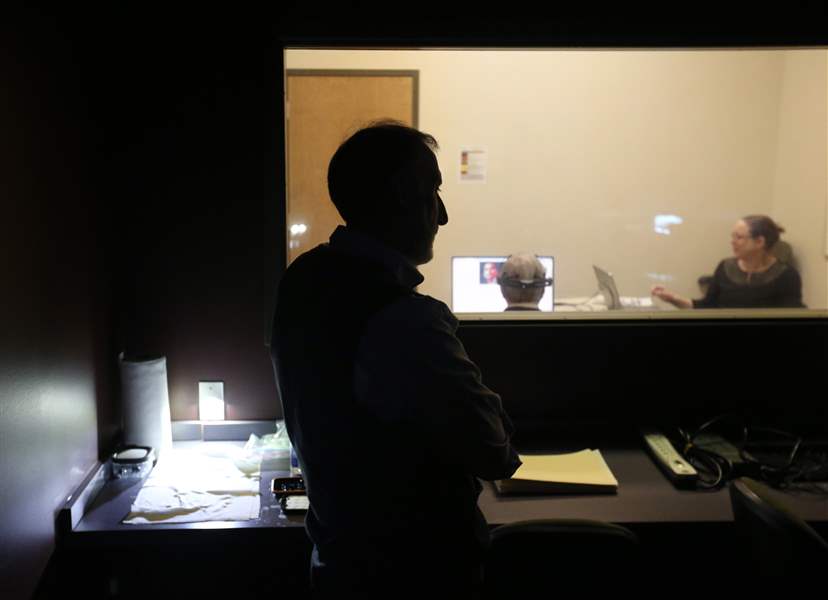

A researcher monitors John MacWherter, above, through a two-way mirror while Kathleen Kennedy of the University of Akron tests him using negative political advertising at the Taylor Institute for Direct Marketing on April 12 in Akron.

AKRON BEACON JOURNAL

A researcher monitors John MacWherter, above, through a two-way mirror while Kathleen Kennedy of the University of Akron tests him using negative political advertising at the Taylor Institute for Direct Marketing on April 12 in Akron.

Like the cicadas — only a lot noisier — political ads are about to blanket Ohio and other swing states. And what’s coming is likely to be more negative, more misleading, and more targeted than ever.

For evidence, look to the 14 months leading up to the Iowa caucuses and New Hampshire primary. More than 133,000 national broadcast and cable TV ads aired — at a cost of more than $156 million. Those numbers from the Wesleyan Media Project don’t include efforts to sway hearts and minds in any of the rest of the primaries and caucuses — including Ohio’s — nor in the general election.

And while the ads started out on a positive note, they pivoted to nasty pretty quickly. And those who watch the claims and patterns of the ads say the reason is pretty simple: PACs and outside groups.

On the GOP side alone, ads from outside groups — as opposed to the candidates themselves — are up more than 23,000 times the rate in 2008. And they already account for more than half the ads and three quarters of the spending in this presidential campaign cycle.

RELATED CONTENT: Stories, videos at Your Vote Ohio 2016

Travis Ridout — one of the directors at the Wesleyan project and a professor at Washington State University — says candidates are aware of potential backlash from attack ads.

Your Vote Ohio logo

“But if it’s some group, especially a group you’ve never heard of before, there’s no real accountability, no way to hold those groups responsible for attacks they [voters] may not like,” Mr. Ridout says. “And therefore, the groups can get away with it.”

Kathleen Kennedy, a lecturer at the University of Akron who specializes in commercial advertising, agrees outside groups make all the difference in tone.

“If brands could have outside political action committees, we wouldn’t want to turn on our TV sets, or listen to the radio, or hear commercials,” she says.

Ms. Kennedy has spent a lot of time lately in the marketing lab at the University of Akron. One-by-one, she has outfitted about a dozen people with delicate headgear to measure their reaction as they’re bombarded for about a half-hour with political ads. She measures their EEGs, tracking their eyes, and watching the tiniest of facial expressions. It’s all common stuff in brand research. What she wants to find out is if it works in political advertising, too.

“Our goal is to really look at how do these ads perform and what emotional response do they elicit, unrelated, somewhat to people’s political views,” she says.

Separate from the biometric readings, she asks people to rate the ads by five measurements: how pleasant, important, informative, believable, and fair. But the axis of two of those points is what really matters: pleasant and informative.

And pleasantness is very much in the political eye of the beholder.

For someone like Sheri Risaliti — a study participant and Bernie Sanders supporter, and no fan of Ted Cruz: “I really didn’t like anything with Ted Cruz in it. That picture of him, just revulsion.”

Then there’s Amy Schwan, a Donald Trump supporter who can’t stand Hillary Clinton.

Ms. Kennedy presses her.

“Is there any ad that you could watch for Hillary without cringing?”

“Maybe,” Ms. Schwan responds. “If she wasn’t speaking or if her face wasn’t on it. If it just maybe talked about her accomplishments.” Then she adds quickly: “I don’t think there are any.”

John MacWherter views a negative political advertisement for Donald Trump during a study in April in Akron. As the amount of political ads increases this election season, researchers are studying how viewers react to the messages.

Beyond politics

But Ms. Kennedy says some ads transcend political points of view — both conscious and subconscious.

Just about everyone agrees that a Bernie Sanders ad set to Simon and Garfunkel’s “America” is very pleasant — and very meaningless.

Everyone says an ad featuring a nearly nude photo of Melania Trump is out of bounds.

And a “Lyin’ Ted” Cruz ad — featuring his increasingly elongated nose wrapping around his neck — most folks saw it as “creepy,” even if they thought it was true.

What’s out of bounds?

Both the “Lyin’ Ted” and “First Lady Melania” ads are attack ads — the kind most people say they hate. But if trends hold, those are the ads that are likely to pound voters in swing states over the next six months.

After all, 60 percent of the ads went on the attack in 2012, up from 50 percent in 2008 and less than 30 percent in 2000.

Chance York, who teaches political advertising at Kent State University, says the reason is pretty simple.

“When you attack the other side, that’s when you open up the idea of persuasion,” he says. “You may not at a conscious level have your audience saying, ‘Oh I’m really doubting this candidate now.’ But at kind of a subconscious level, they’re saying, ‘Well, maybe there is something to this attack. Maybe this person isn’t who I thought they were.’”

Mr. York adds a huge caveat. The pool of persuadables is a really shallow one.

“Some research has shown negative advertising can only swing about 1 percent of voters either way. So if you want to attack, attack, attack an opponent, you’re not going to get a lot of return on investment.”

Then he adds a caveat to the caveat: Sometimes, in some swing states like Ohio, 1 percent is all you need.

Not all bad

Most people see negative ads and attack ads as the same thing — and political scientists define negative advertising as anything that mentions an opponent’s name. But not all negative ads are created equal.

There are the more informative “contrasting” ads that compare positions and resumes of candidates. And the Wesleyan Project’s Mr. Ridout says they can offer a big bonus for voters.

“It can sometimes make them want to learn more information about the candidates,” he said. “Negative ads are also typically more informative. Your typical positive ad is one in which you meet their family, they say they share your values, and you don’t learn much beyond that.”

Contrasting political ads have their commercial-brand parallels — the Coke-Pepsi wars, for example.

So do positive ads. The University of Akron’s Ms. Kennedy says the logic of positive political ads is roughly the same as why Buick wants someone who recently bought a Buick to watch its commercial.

“It’s really important to reinforce how you feel about your car and your product so that you spread that message around. ... It’s very important for candidates to do this. It keeps people energized and motivated.”

And commercial advertising even has its equivalent of attack ads. One example is those pitching home security systems with a message of fear.

But political advertising is where the image of the world as an ominous place takes shape most often.

And Kent State’s Mr. York says there’s a risk when those ads crowd onto the airways.

“If you have two candidates going at it with negative ads back and forth being highly uncivil, it could have an effect,” he says. “Especially with moderate voters, you get a demobilization effect, where they just kind of turn off, ‘this is a nasty campaign, I just want to stay home.’ ”

Unless, he notes, that’s the purpose.

The Akron Beacon Journal’s Doug Livingston contributed to this story.