Passover and the tradition of sharing a Seder meal and a Haggadah story

3/24/2013

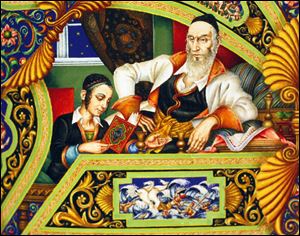

Detail from "The Four Questions" as depicted in Arthur Szyk's "The Szyk Haggadah". Leonard Baskin's "A Passover Haggadah", Ben Shahn's "A Haggadah for Passover", and Arthur Szyk's "The Szyk Haggadah" all owned by the Toledo Museum of Art.

Many Jews and other religious people mark Passover with the tradition of sharing a Seder meal and a Haggadah story, which tells about the Hebrew people during the scriptural time of their captivity in Egypt and their exodus to freedom. It is a time for family, including children, and friends.

Seder meals are often served the first two nights of Passover; Hasidic and other Orthodox Jews might have a third meal on the last day, for the messiah who has not yet come. Passover, or Pesach, begins at sundown Monday and the holiday lasts eight days, ending when daylight is over April 2

The Seder "is an amazing ceremony," said Toledo native Ira Steingroot, the author of Keeping Passover: Everything You Need to Know to Bring the Ancient Tradition to Life and to Create Your Own Passover Celebration (HarperCollins).

"The [Haggadah] book itself is just like the script of a play, which involves some amount of variation and improvisation in the enactment of it at each Seder. It's not something you do in the same way every year. It is actually a great learning device that involves all the human senses, in which food is part of the experience of the re-enactment."

An artistic Haggadah contributes to "the intense experience that we're expected to have that combines food and music and art, the intellectual aspect of the story we're reading, and so on, right up to the scent of horseradish entering your nose and giving you that burning sensation that you love and recoil from."

The Haggadah traditionally begins with blessing and preparation: giving thanks, drinking a cup of wine, washing hands, and breaking bread.

Four questions are always asked about why the Passover meal is different from all other nights: Why do we eat unleavened bread? Why do we eat bitter herbs? Why do we dip the herbs in salt water and a sweet garnish? Why do we eat with special ceremony?

The answer is given in the narration, or the telling, and includes references to the 10 plagues and other mentions of the Hebrews' struggles. There are songs and particular foods to taste that relate to the story. Then a full meal is shared, and the Haggadah typically closes with a final blessing and a prayer that next year those gathered might celebrate Passover in Jerusalem, symbolism for a place of freedom and religious celebration.

The Toledo Museum of Art has three Haggadot, the plural version of the word. They went on exhibit Tuesday, March 19, and will remain on view until Sunday, April 7.

The museum's most recent Haggadah was acquired in 2012 and is a copy of the Szyk Haggadah. Museum curator Tom Loeffler said the illustrator, Arthur Szyk, an American who was born in Lodz, Poland, is "very well known, primarily for his work during the war as a propagandist against the Nazis."

"The Szyk [Haggadah] in particular is quite amazing, with its two volumes and selection of prints," said Mr. Steingroot. The museum has a 2008 color reprint of Mr. Szyk's original 1940 publication.

New Jerseyan Leonard Baskin's A Passover Haggadah was published in 1974. "That's a Reform Haggadah," Mr. Loeffler said. "It was a reinterpretation of the Haggadah for the modern audience."

Haggadah for Passover by Ben Shahn is from 1966, and it includes some hand-colored pictures. Mr. Shahn was an American immigrant from Lithuania. His Haggadah "is his memories of the Passover Seder," Mr. Loeffler said.

"The Shahn is also an act of political statement," Mr. Steingroot said. "In the original, there were actually swastikas on some of the Egyptians...and these were eliminated when they were reprinted. The repetition of history is, of course, a key thing in the Haggadah."

Mr. Loeffler said that Mr. Szyk, Mr. Baskin, and Mr. Shahn illustrated their Haggadahs "because of the importance of religion in their lives. Baskin was the son of a rabbi, Shahn was very much involved, and Szyk was involved in his religion all his life. I think it was a love of the holiday itself [that drew them to the Haggadah] because this really is a time of rejoicing, of celebrating the deliverance from Egypt."

On the exhibit's closing day Mr. Steingroot, now of El Cerrito, Calif., will present a lecture in the museum's Little Theater from 2 pm. to 3 p.m. with slides of 700 years of Haggadot, and he will include comments about the three editions at the museum. "The museum is one of my favorite places in the world," he said, and "is now in possession of three of the most beautiful books."

Contact TK Barger at: tkbarger@theblade.com, 419-724-6278 or on Twitter @TK_Barger.