James A. Rhodes, 4-term governor, dies

3/5/2001

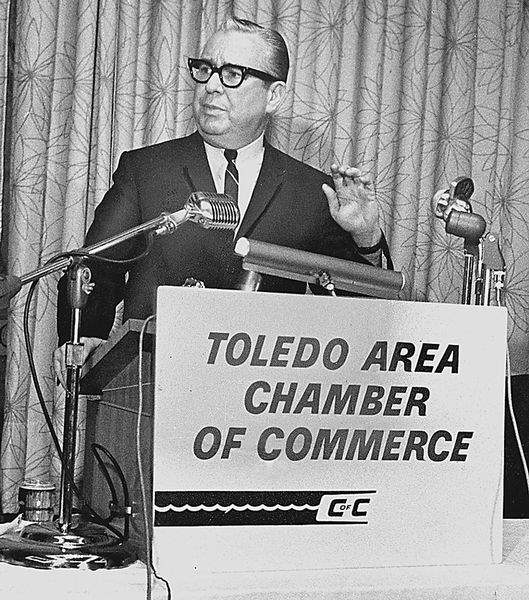

For Gov. James A. Rhodes, Toledo was a frequent stop. Here, he addresses the chamber of commerce in 1967.

blade

CTY PAUL BLOCK PORTRAIT DEDICATION 1 (JEREMY WADSWORTH) AUGUST 25, 1999. GOVERNOR JAMES A. RHODES SITS IN FRONT OF A PORTRAIT OF PAUL BLOCK JR. WEDNESDAY NIGHT AT THE PAUL BLOCK JR HEALTH SCIENCE BUILDING AT MCO.

COLUMBUS - James Allen Rhodes, a four-term governor who became one of Ohio's most enduring political figures of the 20th century, died yesterday. He was 91.

Mr. Rhodes died at 2:45 p.m. at Ohio State University Medical Center from heart failure and complications from an infection, said hospital spokesman David Crawford. He said family members were with Mr. Rhodes when he died.

Mr. Rhodes' career, which spanned nearly 60 years, was buoyed by a folksy, optimistic manner that proved popular with voters; an uncannily accurate political compass, and an apparently indomitable personal will to succeed.

During three terms as auditor and a 16-year tenure as governor - the longest in Ohio history - he dominated state government and politics from the late 1950s into the mid-1980s as a garrulous advocate of “jobs and progress.”

Governor from 1963-71 and 1975-83, he is perhaps best remembered for spearheading the major expansion of state-supported technical colleges and universities around Ohio, including establishment of the Medical College of Ohio at Toledo in 1964.

Mr. Rhodes' passion for public projects will keep him immortalized. No fewer than eight public buildings in Ohio bear his name, and there's a bigger-than-life bronze statue of him on a pedestal outside the Rhodes State Office Tower in Columbus. Critics, and even some of his supporters, observed that his psychological bent to have his name chiseled in stone amounted to an “edifice complex.”

An unabashed booster of Ohio around the country, he also attracted bemused national attention with a variety of proposals - the same critics called them harebrained - such as building a bridge across Lake Erie to Canada.

Unintended national notoriety came in 1970 with Mr. Rhodes' decision to order Ohio National Guard troops onto the Kent State University campus, where four students were killed and nine wounded when guardsmen opened fire during an anti-war demonstration on May 4. Five years later in a civil trial, a federal court jury cleared him of liability.

The shootings, which dampened further demonstrations across the nation, were a turning point in the divisive Vietnam War era. Mr. Rhodes said little publicly about the incident, then or since, commenting after the 1975 jury verdict, “It was the most sorrowful day of my life. I had a duty to perform, and I performed that duty.”

An inadvertent master of the malapropism, Mr. Rhodes' speaking style made him the political equivalent of Casey Stengel. At Ohio University, he once welcomed President Lyndon Johnson to “this venereal institution.” But his chronically fractured syntax, and his career-long habit of speaking of himself in the plural - as in “We have no objection” - never seemed to impede his message.

He was dubbed “The Heavyweight Champion of Ohio Politics” late in his career, but he actually began and ended his statewide reign with losses. The first was a defeat in the 1950 Republican primary for governor and the last was a humiliating whipping in 1986 by longtime Democratic enemy Richard F. Celeste, who beat him for a second term.

Nonetheless, he had a confident instinct for what the public would put up with from its state government, and as governor he shepherded Ohio through the economic boom times of the 1960s, declaring that all of society's ills could be solved with plenty of jobs. A champion of tax breaks for business and industry to help create those jobs, he trumpeted, “Profit is not a dirty word in Ohio.”

After the boom faded in the mid-1970s, he spent much of his last eight years in the governor's office wrestling with fiscal problems that ultimately led him to abandon another favorite slogan, “No new taxes.”

Throughout his career, Mr. Rhodes was never a stranger to Toledo or Toledo politicians. He twice ran for the governor's office and won against Toledoans. As governor he played an important part in the establishment of the Medical College of Ohio and the building of a government center building in downtown Toledo.

This year, The Blade's editorial page urged the state to name the new I-280 bridge being built over the Maumee River after Mr. Rhodes.

“He was always a nontraditional Republican who reached out to both parties, spanning political divides for the common good,” a Jan. 4 editorial in The Blade stated. “How fitting, then, that his name would grace a bridge spanning one of Ohio's greatest rivers, a bridge that will stand as the largest capital project ever undertaken.”

In 1956, he thrashed Joseph T. Ferguson for a second term as state auditor in a mostly Republican year in which Toledo's Democratic mayor, Michael V. DiSalle, lost to Attorney General C. William O'Neill in the governor's race as Frank Lausche moved up to the U.S. Senate.

In 1958, Mr. DiSalle came back to beat Mr. O'Neill for governor, and in 1960 Mr. Rhodes won a special two-year stint as auditor, as terms of all administrative state officials were switched to four years under a 1954 constitutional amendment.

For Gov. James A. Rhodes, Toledo was a frequent stop. Here, he addresses the chamber of commerce in 1967.

That set the stage for a nasty 1962 campaign in which Mr. Rhodes hammered Governor DiSalle as “Tax Hike Mike” for tax increases during his term and for alleged improprieties in an interstate highway project and state liquor contracts.

In an October counterattack, DiSalle backers posed what they called “the $54,000 question.” They claimed that Mr. Rhodes had improperly borrowed $36,000 from his campaign fund, and had converted another $18,000 from a “political slush fund” to personal use from 1955-57. Having failed to declare the money on his federal tax returns, the Democrats charged, Mr. Rhodes got special treatment when the Internal Revenue Service made him pay up in 1958.

Mr. Rhodes took the attacks personally, lashing out in a speech to Republican women at what he called “a sinister and evil attempt” by Mr. DiSalle to obscure the issues and to “vilify and sully my good name, as well as the good names of my wife, my family, my sisters, and my late widowed mother.”

In what was to become his trademark style of political hyperbole, he declared, “This man, seeking to sit in judgment on the entire human race while representing himself as the paragon of kindness and virtue, has attacked me with blobs of slime and vicious fictions. I do not resent his attacks upon me, for I am here to answer them. I have nothing to hide as a public official or husband or father of three daughters.”

Mr. Rhodes said he had paid back the $36,000 with interest, contended the $18,000 was merely reimbursement for travel and other expenses, and insisted he had paid all taxes due. Critics claimed he never fully answered the charges, but the voters apparently believed him. On Nov. 6, he defeated Mr. DiSalle with 59 percent of the vote.

He would serve two consecutive terms, sit out four years while Democrat John J. Gilligan occupied the office, then come back to win two more terms, en route to the longest tenure of any Ohio governor and one of the longest in the nation's history.

In 1966, he trounced Toledoan Frazier Reams, Jr., in the governor's race.

One of his early projects after taking office was the Medical College of Ohio at Toledo, authorized by the General Assembly in late 1964. The day before Christmas, Mr. Rhodes appointed the first board of trustees, including Paul Block, Jr., then publisher of The Blade, who had pushed for the school's establishment and was its first board chairman.

Receiving an honorary degree from MCO in 1982, Mr. Rhodes told a commencement audience that Mr. Block, who would die in 1987, had been “in my office every day around 7:30” in the project's early years to make sure it progressed.

On Aug. 25, 1999, Mr. Rhodes made a rare public appearance at the unveiling of a portrait of Mr. Block at the MCO building that bears Mr. Block's name.

When it came to establishing MCO, Mr. Block provided the idea and Mr. Rhodes lined up the state funds.

“He asked me about this [MCO], and I said, `Paul, I have my money belt on. Let's take it on,'” Mr. Rhodes recalled in an 1999 interview.

That process would be repeated in the late 1970s on another Toledo project, the city-county-state office tower downtown on Jackson Street between Erie and Huron. Although the project was proposed to state officials in 1973 when Mr. Gilligan was governor, it did not move ahead until Mr. Rhodes was back in the Statehouse. Mr. Block, a prime mover in downtown redevelopment, selected the architect, Minoru Yamasaki, and made numerous trips to Columbus to ensure that the governor kept planning and construction on track. Ground was broken in 1981 and the $61 million building was occupied beginning in April, 1983.

The facility was first named for Mr. Rhodes, but the decision was reversed after Democrats took control of the Ohio Building Authority. On June 18, 1986, the structure was renamed for Mr. DiSalle, the former mayor and governor. Officially, the building is the Michael V. DiSalle Government Center, but locally it is known simply as Government Center.

The medical college also would get and give fiscal expertise from and to the state with the help of Toledoans who would later be hailed as some of Mr. Rhodes' best appointments as governor.

One was Howard Collier, who entered state government in 1963 as assistant to finance director Richard Krabach. Mr. Collier moved up to the top spot in Mr. Rhodes' second term, then moved to MCO as vice president of administration when the governor left office in 1971. During the second two terms, Mr. Collier would twice return to the state payroll on extended leaves to lend his expertise to help bail Mr. Rhodes out of tight political corners. Both were during state fiscal crises, in 1980 and 1982.

One of Mr. Collier's proteges at MCO, William W. Wilkins, succeeded his old boss as state budget director in 1976, and went on to serve as administrative services director before leaving government in 1981.

A second Collier trainee, Toledo native William Keip, replaced Mr. Wilkins as state budget director in 1979 and moved over to be administrative services chief when Mr. Collier returned to Columbus in 1982.

Another notable Rhodes appointment was Martin Janis, who had been elected state representative from Toledo in 1960. During the first Rhodes terms, Mr. Janis directed what was then the Department of Mental Hygiene and Correction. In the second two terms, he was director of the state Commission on Aging, and is best known for his part in formation of Ohio's Golden Buckeye Card discount program for senior citizens.

Born Sept. 13, 1909, in the village of Coalton in Jackson County, Mr. Rhodes was the third of five children of James and Susan Howe Rhodes. Although he maintained a carefully crafted image as a poor son of the southern Ohio coal fields, a recent biographer noted that his father was a former miner with some business college education who had advanced to mine superintendent. The family moved to Indiana in 1910 and the elder Rhodes died in 1918, forcing the now-poor Mrs. Rhodes to take 9-year-old Jim and two sisters back to Jackson County.

According to the Almanac of Ohio Politics, Mrs. Rhodes supported the children with a job in a cigar factory and by running a boarding house. In 1923, she moved the family to Springfield, where young Jim showed the early bloom of entrepreneurship by selling advertising for ink blotters, booking bands for dances, and working in a grocery store.

After graduation from Springfield High School in 1930, Mr. Rhodes went to Ohio State University on a minor basketball scholarship but did not last long in academia. Accounts vary on why he left after only one term. The official campaign-biography version is that he dropped out to support his ill mother. Years later, in 1969, OSU began an investigation of a records-department leak after a newspaper report revealed that he was on academic probation after his first and only quarter.

In the meantime, he opened a restaurant - Jim's Place - near the OSU campus, and began to make his way in Columbus politics. In 1934, at the age of 25, he won his first public post, as GOP ward committeeman. From then on, he was clearly a man on the run, jumping from post to post, always moving up.

Scandal touched Mr. Rhodes occasionally, but he had what even his opponents regarded as an amazing facility for shucking off the purported misdeeds of himself or associates. In 1969, as he was preparing to run in the Republican primary election for the U.S. Senate against Robert Taft, Jr., Life magazine published an article headlined “The Governor and the Mobster,” which, while providing no proof, strongly implied that Mr. Rhodes had taken a bribe for commuting the first-degree murder sentence of Thomas “Yonnie” Licavoli, making the 1930s-era Toledo gangster eligible for parole.

Less than a month before the May, 1970, primary, Mr. Rhodes filed a $10.3 million libel suit against the magazine, saying he had commuted Licavoli's sentence on the recommendation of the state parole board because the aging mobster was ill and nearly blind after 35 years in prison. He called the article “a plot by my political enemies to destroy my usefulness as a public servant.”

He dropped the lawsuit when Life issued what amounted to an apology, but he would lose by an electoral hair's breadth, just a day after what would prove to be the darkest hour of his career, the Kent State shootings.

The week before, Mr. Rhodes had ordered National Guard troops onto the Ohio State University to quell student protests against campus racial problems and President Richard Nixon's decision to send troops into Cambodia. Similar protests spread to other colleges and universities, and on Saturday night the Reserve Officers Training Corps barracks at Kent State University was burned during a demonstration.

Mr. Rhodes sent 600 guard troops to Kent and on Sunday personally made a visit. He ignored a request to close the university, said he was going to declare a state of emergency, and held a press conference. According to the report of the President's Commission on Campus Unrest, the governor blamed the disturbances on “the same groups going from one campus to the other” with “definite plans of burning, destroying, and throwing rocks at police and at the National Guard and at the Highway Patrol.” He vowed, “We're going to eradicate the problem. We're not going to treat the symptoms.”

He further castigated the demonstrators as “worse than the brown shirt and the communist element and also the night riders and vigilantes. They're the worst kind of people we harbor in America.”

On Monday, with the university still open and classes being held, 98 guardsmen tried to break up a noon rally of 2,000 students in scattered groups. For reasons never fully explained, the guardsmen, who had been subjected to rock-throwing and harassment, fired a 13-second volley of 61 shots across campus from the top of a hill.

Of Mr. Rhodes' role, the national commission's report said: “Many persons felt that the governor had spoken firmly and forthrightly. Others felt that his remarks were inflammatory and worsened an already tense situation. Some, including many Kent students, believed the governor was hoping that his words and actions at Kent would win him additional votes in the primary election. ...”

In his final term as governor, Mr. Rhodes became increasingly cagey in his relationship with the news media, often flying off to other states or his Florida condo without notice or explanation. He had always had a love-hate jousting with the press, which he described as “like being a dog in heat. You stand still and they'll screw you. You try to run and they'll chase you and bite you in the ass.”

Unfortunately for him, his lame-duck term from 1979-83 was a continual battle with dwindling state revenue, school closings, and related fiscal crises, and reporters delighted in sticking the “no-new-taxes” executive with the responsibility for tax increases that were to come.

He initially resisted new taxes, cutting state spending and pushing hard instead for establishment of a state loan fund schools would have to dip into to stay open. When that didn't work, in late 1980 he presented a $395 million package of “temporary” taxes, including a boost in the sales tax. In the midst of all this, voters rejected another of his bond issues, this one $500 million for new highways.

At the same time, Mr. Rhodes was again flirting with the national political spotlight. He personally shepherded Ronald Reagan around Ohio during his 1980 presidential blowout against Jimmy Carter, encouraging Mr. Reagan to refer to the economic recession as he would - a “depression” - and planting the idea in the former California governor's mind, and rhetoric, that trees cause more air pollution than automobiles.

A Republican with roots in the John L. Lewis coal-mining tradition, Mr. Rhodes consistently displayed a bent for political deals that were distinctly bipartisan when they were to his advantage.

Veteran Ohio political writer Abe Zaidan described this as “the sort of partisan impurity that outrages some Republican thoroughbreds. He is, by most assessments within the party, a `loner' whose political commitments begin and end with his survival.”

In 1968, it was reported that Mr. Rhodes had twice declined entreaties by President-elect Richard Nixon to join his cabinet. Later, he seemed to develop a special kinship with Mr. Reagan, but again preferred to work at the edge of the political radar scope, offering advice on policy and tactics.

During one week in mid-March, 1982, after he had publicly ruled out running for the U.S. Senate that year, he met quietly in the White House with the President and, five days later, joined Mr. Reagan in a private runway huddle aboard Air Force One in Ft. Wayne, Ind., when the president flew there to view flood-relief efforts. “Rhodes,” a Washington source said at the time, “has no compunctions about sitting down with the President of the United States.”

Another side of Mr. Rhodes that he kept even less visible to the public was his apparent distaste for the death penalty, which was carried out only once while he was governor, in 1963. While always sounding tough on crime, he avoided stating his views on sending criminals to “Old Sparky,” as the electric chair was known, while commuting some sentences and making his staff covertly arrange for appeals in other cases. The U.S. Supreme Court reinstated the death penalty in 1976 and it wasn't restored in Ohio until 1981.

With Ohio's economy still declining in the election year of 1982, Mr. Rhodes had to swallow hard once again on taxes. He and legislative leaders eventually presented a $1 billion package that included $411 million in selective spending cuts and $591 million in taxes, including an income tax surcharge and higher rates for the wealthy. Although he clung publicly to the fiction that these tax increases would be temporary, rather than permanent, he was leaving that decision to entangle his successor, Mr. Celeste.

On Dec. 5, 1982, a month before he left office for the final time, a crowd of about 200 on the northeast corner of the Statehouse lawn witnessed the unveiling of a bronze statue of Mr. Rhodes. In classic Rhodes style, authorization for the 6-foot monument had been slipped into a prison construction bill, to be paid for with private funds. During the ceremony, Mr. Rhodes asked the audience to pray for Ohio's unemployed residents. Overlooking the scene, state Auditor Thomas E. Ferguson, a bitter Rhodes opponent, had placed a sign in his office window. It read: “Remember Kent State.”

That Mr. Rhodes would try for yet another political comeback - running for governor for the seventh time in 1986 at the age of 77 - would seem to be a dismal footnote to his long career. Against the wishes of some Republicans, he brushed aside younger opponents, state Sens. Paul Gillmor and Paul Pfiefer, in the GOP primary, en route to a rematch with Mr. Celeste.

By most accounts, he ran an unimaginative, negative general-election race and was outspent, outcampaigned, and outclassed in losing to Mr. Celeste, 61 percent to 39.

But it was further proof of what Robert Hughes, Cuyahoga County Republican chairman, often said about this legend of Ohio politics: “If he's breathing, he's running.”

And Mr. Rhodes remained active throughout the 1990s, regularly attending the opening of his beloved Ohio State Fair.

In 1999, Mr. Rhodes lectured political leaders in Lucas County who were squabbling over the location and size of a new downtown stadium for the Toledo Mud Hens. He said unless city and county officials reached an agreement quickly, the state would not provide funding.

“You have to tell [state leaders] what you want. They can't read your minds,” he said.

Governor Taft, who will return to Ohio from a South American trade mission to attend Mr. Rhodes' funeral this week, said: “His passing closes not one, but several chapters of Ohio history.”

RHODES' SERVICES

Mr. Rhodes' funeral is planned for 10 a.m. Thursday in Upper Arlington Lutheran Church, 2300 Lytham. Burial will be in Greenlawn Cemetery, 1000 Greenlawn Ave. in Franklin Township near Columbus, the Schoedinger Funeral Service said.

Visitation is from 4 p.m. to 7 p.m. Tuesday at the church. His body will lie in state in the rotunda of the state capital from 7 a.m. to 2 p.m. Wednesday.

A private funeral service will be held at 2 p.m. Wednesday in the statehouse atrium.

Flowers can be sent to the church. The Rhodes family had not decided on any foundations for gifts.

Blade staff contributed to this report.