BEHIND THE CURVE: OHIO'S KILLER CORRIDORS

Oregon state effort serves as model for problem roads

‘Safety corridor’ program helps to reduce fatal crash rate

11/16/2004

Part three of a three-part series.

Working the cash register at T.J's carryout, Micci Ries watched the emotion drain from the face of a local firefighter as he talked about the latest crash on the "Highway of Death."

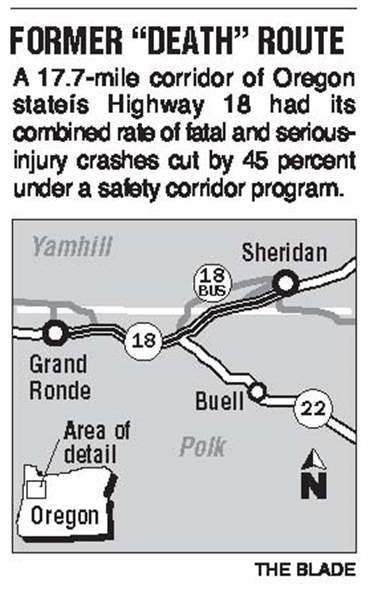

Six people already had died on that notorious stretch of Oregon's Highway 18 in the past year. And now the dead included two teenage sisters - and the fetus that one was carrying.

So that weekend in January, 1999, the 49-year-old part-time cashier from tiny Sheridan, Ore., cried and pledged to devote her time to making the road safer.

Her state lacked a big pot of cash to redo the 18-mile stretch of highway, but it offered a program that teamed up local residents, highway engineers, police, and traffic safety experts to figure out relatively inexpensive ways to cut serious crashes.

Five years later, tears well in her eyes as Ms. Ries describes the results: "It worked. It really worked."

READ MORE: Behind the curve: Ohio's killer corridors

Oregon had designated that stretch a "safety corridor," and under that program the rate of fatal and serious-injury crashes has been cut nearly in half.

Other safety corridors in Oregon have seen drops as high as 80 percent as part of a traffic-safety concept that's spread across the country. In the last 16 years, eight states have adopted some version of safety corridors.

Ohio began a pilot program 10 years ago, but dropped the concept and now relies on more traditional models of traffic safety.

Now, unless the state can afford to rebuild a dangerous stretch of road, which it rarely can, each traffic safety agency generally does its own thing.

Highway engineers calculate the worst intersections and tiny segments of road, and re-engineer them. State troopers make their own lists of bad spots, and they patrol them more often. State traffic-safety administrators funnel cash to police departments willing to combat bad driver behaviors, such as drunken driving.

But agency representatives don't all get together in one room with local residents and talk about a particularly bad stretch of road. They don't all brainstorm together on how to fix the problems on those stretches, and they don't pool resources to get the job done.

They don't do what the state of Oregon did for Micci Ries.

Born from a program developed by the Pennsylvania Department of Transportation in 1988, the safety corridor program gained popularity after the Federal Highway Administration listed it in 1990 as one of the five most promising short-term safety programs in the country.

Helping problem spots

Proponents say it's not a cure-all. Often, the best solution to boost safety is to rebuild a road - such as turning a busy two-lane highway into a divided four-lane freeway. But such rebuilding projects are extremely pricey and time-consuming and often harm the environment. Safety corridors serve as a stop-gap to at least reduce serious crashes on a dangerous stretch of road until money can be found to rebuild it.

That's why Oregon began the program 15 years ago. Its Department of Transportation took suggestions from residents and legislators about bad stretches of road, and then crunched the crash numbers to prioritize them.

Sometimes Oregon's DOT had routes with such bad reputations that they ran the numbers without even being asked. That was the case with Highway 18.

The mostly two-lane highway from Portland to Oregon's Pacific coast had become a popular tourist route to new casinos, with serious crashes skyrocketing on the corridor near Sheridan. The DOT made it a safety corridor in 1996 and began some engineering fixes.

But, showing just how powerful public involvement is in such programs, the safety corridor didn't really improve much until after that crash in 1999. The sisters, 18 and 19, pulled out to pass a car and were hit head-on by a Ford Explorer.

After spending hours on the crash scene, a volunteer emergency medical technician stopped in Ms. Ries' carryout a half-mile away and described the crash. Ms. Ries and the firefighter formed a game plan to gain community and state support. A local committee was formed to work with the state's corridor program. State engineers joined residents, school officials, police, and politicians.

Soon they were taking bus tours of the stretch of highway, and ideas were flowing, recalled committee member Mike Propes. On one trip, the police complained that they couldn't monitor traffic on one part of the stretch because there was no spot to safely pull off the road. A resident offered a simple suggestion: Build a pull-off.

"Then the guy said, 'Well, gosh, we can do that for a couple hundred dollars,' " Mr. Propes recalled. "We did that, and the police sit there all the time now, and it has slowed traffic down tremendously."

On other stretches, where motorists were falling asleep or trying to pass in heavy traffic, the committee got the narrow road widened enough to cut out rumble strips on the shoulder and in the median to alert drowsy drivers or scare aggressive ones.

That first year, as the committee formed a plan, the number of fatalities along the route shot up to 11. But the next year, as the fixes and heavy enforcement and public education programs were conducted, the number of dead dropped to zero. Ever since, the number of fatalities has been one or two a year.

A few complaints

Still, not everybody is happy with every part of the program.

Among the biggest complaints is the program's name. Motorists entering a "safety corridor" can be confused into thinking the signs mean it's a safer place to drive, not a dangerous stretch, said Ms. Ries and committee member Val Adamson.

And, because the route has improved so much, Oregon's DOT wants to decommission it as a safety corridor, which leads Ms. Ries to fear that deadly crashes again will spike.

But those involved still consider the program a major success - and a much more realistic solution than simply waiting for the state to plan and build a new four-lane highway.

"The engineers can engineer something to death, and then they'll turn around and say, 'It's going to cost $35 million and we don't have it, so put it on a shelf,' " Mr. Adamson said. "This was a little nickel, dime fix that came out of maintenance money and shared equipment. It was just a shoestring deal, and it worked."

That's one of the benefits of the program lauded across the country. Some improvements cost as little as $10,000 to $20,000 per mile over the life of a corridor - relatively inexpensive in an era when new highways can cost several million dollars per mile.

Ohio's response

When told of the other states' programs, Ohio Department of Transportation Director Gordon Proctor insisted his agency is among the nation's leaders in safety engineering fixes. And he said the agency occasionally has met with the public and others interested in low-cost fixes over stretches of road.

But he said the agency never has heard of the success of such a corridor program, as employed by the eight states.

"We meet constantly with [the] Federal Highway [Administration]. They have never come to us and said, 'This is a proven program that should be adopted.' Every year we go to the annual summits. It's not come up," he said.

But it's come up in the Federal Highway Administration's awards. California's corridor program snagged one in 2003.

That federal agency's sister - the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration - last year cited New Mexico's program among the nation's most "innovative" state and local safety projects. Washington state's program also won a 2003 award from the Washington, D.C.,-based nonprofit group Public Employees Roundtable.

And the programs have supporters like Richard Pain, the transportation safety coordinator of the Transportation Research Board, which advises the federal government and others on scientific research.

"The impact of this [program] is to go across organizational silos and start combining efforts and maximize the impact instead of spending the same amount of money and not getting much impact," he said.

And to Tom Bryer, the safety engineer who began Pennsylvania's program, every state has notorious road corridors that can benefit from a collaborative program, if states are willing to take a broader, long-term look at the data.

"You shouldn't walk away from something like that when you see it," he said. "

ODOT is in the best financial position of Ohio's three traffic safety agencies to start such a program, with a $65 million safety budget that's second only to California's. But the agency has no plans to start one, although Director Proctor said he'd be open to participating in one if people requested it.

Residents along Oregon's Highway 18 say they're glad their state welcomed their help.

"Sometimes a group of local people really know the problem better," Mr. Propes said.

"And working in a group like this and working as a team, you can really identify some cheap fixes and get better [driver] education. This really shows it worked."

Contact Joe Mahr at: jmahr@theblade.com or 419-724-6180.