Emergency manager: Detroit debt deal necessary

Settlement over debt with 2 banks would end 'sordid tale,' Orr says

1/3/2014

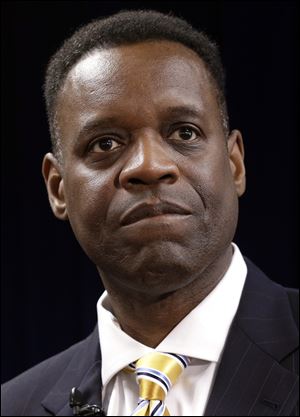

Kevyn Orr

DETROIT — Detroit’s state-appointed emergency manager said today that an agreement to pay off banks and settle millions of dollars in debt tied to an interest rate swap deal resolves a “sordid tale” and fuels a massive recovery plan for the broke city.

Kevyn Orr testified in federal court that the proposal to terminate the deal for $165 million is best for Detroit, adding that it removes significant financial and legal risks and allows the nation’s largest public bankruptcy restructuring to proceed.

“It finally resolves this issue — the whole sordid tale of the swaps — and provides the city with an opportunity to finally do some reasonable, strategic planning for years to come,” he said. “The city needs to stabilize its finances once and for all. It needs to get out from under this whole swap contract. ... The city cannot plan unless it removes this potential risk from the table.”

Detroit, which filed for bankruptcy in July, pledged casino tax revenue in 2009 as collateral to avoid defaulting on pension debt payments. The swaps allowed Detroit to get fixed interest rates on pension bonds with UBS and Bank of America.

The payoff had been $220 million, and Judge Steven Rhodes ordered the city to negotiate a better deal. He must approve the settlement, which is opposed by pension systems and bond insurers. The city also has agreed to lower a financing loan to pay the banks.

Orr said he and his colleagues weighed whether to sue the banks and even approached officials with the Securities and Exchange Commission to investigate. He contended the transactions could have been fraudulent and illegal, but said legal opinions provided to the City Council concluded otherwise and state gambling regulators raised no concerns about the use of the casino tax revenue.

In the end, Orr said, every argument to sue was counteracted by one to avoid litigation. For instance, he said, the city could have recovered millions of dollars in payments if it had won a lawsuit, but a loss could have cost at least as much in legal fees and payments to the banks.

“More importantly from the city’s perspective, the single largest, most secure revenue source for the city would have been imperiled,” he said. “Casino revenue approaches $200 million on a billion-dollar budget — 20 percent of the city’s budget would go away. If that happened to the city, you could not cut enough services.”

Bruce Babiarz, a spokesman for Detroit’s Police and Fire Retirement System, said the city’s two pension systems still oppose the new deal between the city and the banks as “still being too rich” and filed a brief opposing it.

Also finding the settlement unfavorable is Ambac Assurance Corp., which backs Detroit bonds. Caroline English, an attorney representing Ambac, argued while questioning Orr that he never sought a cash-flow analysis showing how much the city could have reaped if it had successfully sued the banks.

Orr has said Detroit’s $18 billion or more debt includes underfunded obligations of about $3.5 billion for pensions and $5.7 billion for retiree health coverage.

Today's hearing was briefly interrupted by a protester. Rhodes called a brief recess as guards removed the man, who yelled, “Jones Day is not the city of Detroit, nor is the emergency manager.” Orr left his role as a partner in the Cleveland-based Jones Day international law firm after the state hired him as emergency manager, and Detroit hired Jones Day to lead a financial restructuring before the bankruptcy filing.

Rhodes told Orr afterward he could leave the courtroom immediately “if there are any further outbursts like this.”