Lake Erie Foundation discusses methods to reduce algae-forming nutrients

12/2/2016

NATIONAL OCEANIC AND ATMOSPHERIC ADMINISTRATION

PORT CLINTON — Western Lake Erie basin agriculture can achieve most of the 40 percent reduction goal set for algae-forming nutrients by doing one thing: Convincing more farmers to inject their fertilizers below ground rather than continuing to spread them along the surface of their land, according to an ongoing research project that involves about 15 Great Lakes scientists.

The project, headed by the University of Michigan, also found that cereal rye cover crops and buffer strips are among the most effective practices at controlling runoff.

Details were presented to about 100 people at an annual forum at Catawba Island Club sponsored by the newly formed Lake Erie Foundation. The foundation is a collaboration between two advocacy groups, the Lake Erie Improvement Association and Lake Erie Waterkeeper. It was set up to encourage more long-term business investment in the lake.

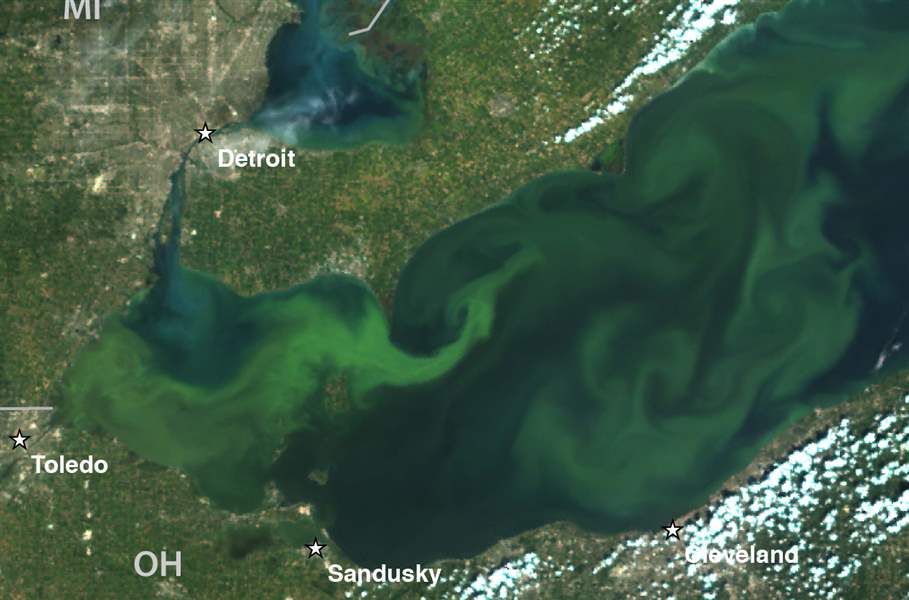

Ohio, Michigan, and Ontario agreed in 2015 that a 40 percent reduction in nutrient loading over 2008 levels is necessary to make meaningful progress in the fight against toxic microcystis algae, which is on the rise globally but getting high-profile attention in the western Lake Erie basin because of the 2014 algae crisis that made Toledo’s tap water unsafe for three days.

Jeff Reutter, Ohio Sea Grant and Ohio State University special adviser, updated the audience on efforts the U.S. and Canadian governments are taking to promote that goal under the latest version of the Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement the two nations signed in 2012 through the International Joint Commission.

The research on most-effective farming practices was presented by Margaret Kalcic, an assistant professor of OSU's food, agricultural, and biological engineering department, who said she was a post-doctoral student under U-M researcher Don Scavia when he began leading the project.

Using a variety of models that show how much phosphorus and nitrogen could be curbed under different scenarios, the research team identified direct injection as the most-effective method at controlling runoff and one that would not reduce crop yields.

The problem is it’s not widely embraced — and needs to be done by at least half of the Maumee River watershed’s farmers to make a big enough impact, Ms. Kalcic said.

“We had hoped that 10 percent on targeted land would do a lot, but found it didn’t,” she said. ”We really have to be looking at actions on farmland.”

The research disputes the notion that a 40 percent reduction is impractical, Ms. Kalcic said.

“We do see there are pathways to that 40 percent and we were able to maintain yields [in their modeling],” she said. ”If we can get the phosphorus into the soil, that does an awful lot.”

Contact Tom Henry at: thenry@theblade.com, 419-724-6079, or via Twitter @ecowriterohio.