Moses Fleetwood Walker gets overdue recognition from state

9/20/2017

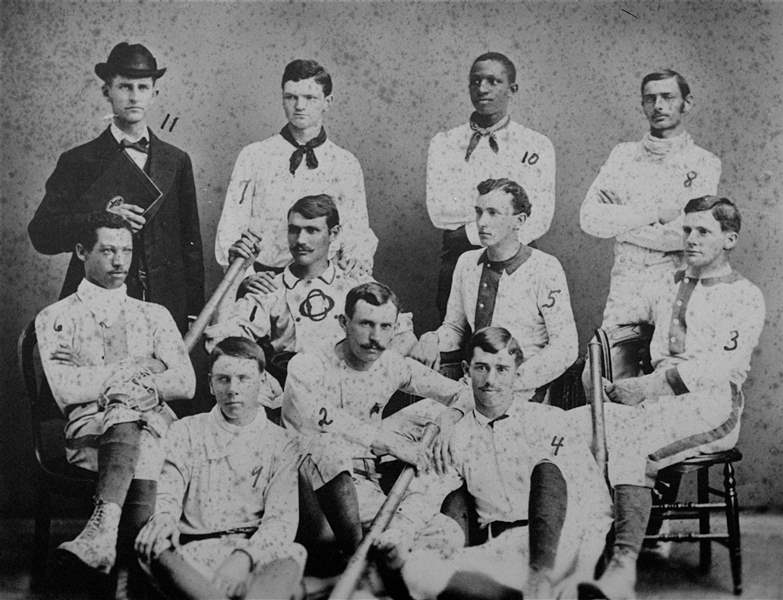

Moses Fleetwood Walker (No. 6 in the middle row) and his brother Weldy (No. 10), pictured at Oberlin College, were the first blacks to play major league baseball for Toledo when the city had a major league team in 1884.

ASSOCIATED PRESS

COLUMBUS — It took three times at bat, but a bill designating one day a year in Ohio to honor the first black man to play major league baseball under contract cleared the decks of the Senate on Wednesday and is on its way to Gov. John Kasich’s desk.

And it wasn’t for Jackie Robinson.

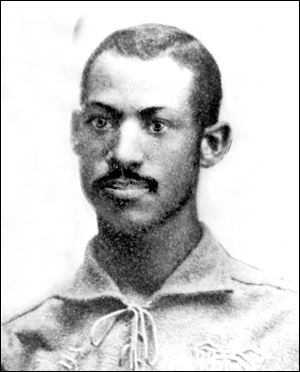

Moses Fleetwood Walker, the first black to play for a major league baseball team. He played for the Toledo team in the old American Association in 1884. He caught 46 games, all barehanded and hit a .251 average.

Moses Fleetwood “Fleet” Walker, played less than a season for the Blue Stockings in Toledo, but the bare-handed catcher unknowingly made history when that short-lived team was retroactively deemed to have joined the major leagues.

The backlash by white players and team owners against playing on the same field as Walker and later his outfielder brother, Weldy, helped lead to erection of the so-called “color barrier” that Robinson would be credited with shattering in 1947.

The Senate approved the measure unanimously.

“Rarely are we given the opportunity to correct past wrongs as members of society, and I think that’s what we are talking about here,” said Craig Brown, an adjunct professor at Kent State University, whose past classes had championed the bill’s passage.

“With Moses Fleetwood Walker, and because of the type of man he was, we are given one of those rare opportunities here,” he said. “He accomplished so much and was as good as any other man in what he chose to do, but due to misinformation and hatred during his lifetime, he was robbed of his due level of success.”

House Bill 59, sponsored by Reps. David Leland (D., Columbus) and Thomas West (D., Canton), recognizes Oct. 7, Walker’s birthday, as Moses Fleetwood “Fleet” Walker Day in Ohio each year. It passed the House overwhelmingly last spring.

“Honoring Moses Fleetwood Walker is more than just honoring a baseball player, because anytime we recognize and celebrate the fight for equality in our society, it moves the whole country forward,” said Mr. Leland, who is on the board for the Columbus Clippers, the Cleveland Indians’ minor league team.

Walker took to the field in 1884 when the Civil War and slavery were still recent history. Injury prematurely ended his season, and the Blue Stockings only survived for a year. But that year was as part of the American Association, which was later considered a major league and eventually merged with the National League.

Walker continued to play in the minors until 1889, but he would never again play on a major league team.

“Though his name is relatively unknown compared to Jackie Robinson’s, he was the first to break the barrier which prevented black men from playing organized baseball,” said state Sen. Edna Brown (D., Toledo), who sponsored an identical bill in the upper chamber.

“In fact, his baseball career began over half a century before Jackie Robinson’s,” she said.

The bill won’t take effect until 90 days after the governor’s signature, so Walker’s birthday will pass this year without the official recognition. But he is slated to be inducted into the Ohio Civil Rights Commission Hall of Fame on Oct. 5 at the Ohio Statehouse.

This marked the third session that the bill has been introduced. On its first pass, it never cleared the House. The next session it passed the House only to be stranded in the Senate.

Walker was born to an African American physician father and white mother near Steubenville in 1856. He was the first black player for Oberlin College, and he played for the University of Michigan before he signed with the Blue Stockings, a new minor league team.

Walker has never gotten the attention that Robinson has, although a timeline credit and photo in an exhibit at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum in Cooperstown, N.Y., mark his place in history.

In 1891, he was tried for second-degree murder for killing a white man who, with friends, had attacked Mr. Walker. Despite the era, an all-white jury acquitted Walker, determining he had acted in self-defense.

He died in 1924. Seventy-six years later the Oberlin Heisman Club financed the erection of a headstone on his previously unmarked grave in Steubenville’s Union Cemetery.

Contact Jim Provance at: jprovance@theblade.com or 614-221-0496.