Biggest peril gorillas face is extinction from hunting

12/11/2000

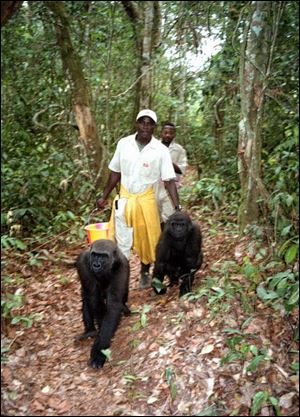

Placido Didi Mouori carries some of the youngest orphan gorillas through the forest at the Project for the Protection of Gorillas.

EDITOR'S NOTE: Commercial hunting is driving apes into extinction in Africa. In September, Blade science writer Jenni Laidman traveled to Gabon, in Central Africa, to document the toll of the bushmeat trade.

Her three-part series tells the stories of the people struggling to save baby gorillas - orphans of the slaughter.

MPASSA, Gabon - A gaggle of curious gorillas shuffles toward the youngster cowering in Linda Percy's lap.

Three gorillas sniff the newcomer in greeting. Ivindo shrinks lower at each inquisitive approach.

Kwam is fourth. He lowers his huge head to Ivindo's shabby fur. The big gorilla smells of the forest, clean and musky. His coat is rich and rough. In the sun, Linda can trace its coarse weave of cocoa browns, grays, and rusty tans.

Ivindo buries his head.

Sophie is next in line. She is the gorilla earth mother, adopting many of the new youngsters when they join the troupe.

Ivindo's fear gets the best of him.

He screeches, pushing his head into Linda's armpit. Linda winces in his tightened grasp. Ivindo screams louder.

The gorillas stop, as though confused by this young one's outburst. Hoping to calm Ivindo, Linda crawls away from the group. It doesn't work. Ivindo keeps pushing and screeching.

Linda struggles to straighten her lanky frame and rise from the forest floor. She's frightened for Ivindo. This is a bad sign.

She had high hopes for this visit. Usually, the orphans rally with this introduction. It helps them settle into their new home at the Project for the Protection of Gorillas in southeast Gabon.

Ivindo was near death when Linda brought him to camp two weeks ago. Until two days ago, he was desperately sick. The trip to meet the gorillas was to encourage his full recovery.

Instead, Ivindo grows sicker.

Returning gorillas to the wild requires a delicate mastery of gorilla culture. The staff at the gorilla project needs to understand gorilla behavior if they are to teach the youngsters to live in the forest. They watch what these sensitive animals seem to want, what makes them calm, what upsets them. It's not always clear. Misunderstandings are inevitable as humans read gorilla minds by interpreting gorilla behavior.

But gorilla culture, though mysterious, is in many ways the easy culture to interpret. Far more complicated, and full of pitfalls for western conservation workers, is the dynamic African culture in which the rescue work takes place.

Even the need to save orphan gorillas is an outgrowth of a culture in flux. Traditional hunting has been distorted into a commercial slaughter. Wildlife experts say this uncontrolled hunting is the main force driving many species into extinction - overtaking even habitat loss as an immediate threat.

These gorilla orphans are all that remain of their slaughtered families.

The ready market for forest meat throughout the cities of central Africa could spell the end for gorillas, chimpanzees, monkeys, and dozens of other species, conservation biologists say. Researchers Margaret Kinnaird and Timothy O'Brien of the Wildlife Conservation Society may have summed it up best in a paper on the worldwide bushmeat crisis published in “Hunting for Sustainability in Tropical Forests”:

“Realistically, if changes in attitude do not occur soon ... a fitting [epitaph] for the loss of endemic mammals and birds may be, ‘They tasted good.'”

Every afternoon when Belinga comes home from playing in the forest with the other gorillas, Liz Pearson gives her a cup of yogurt.

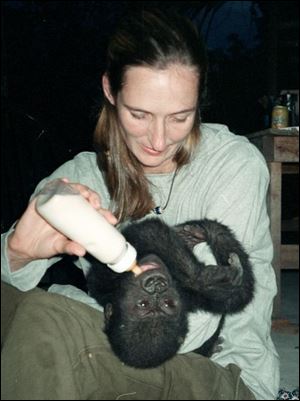

Since Ivindo's arrival two weeks ago, Linda Percy has done much of what a gorilla mother would do: She slept with him, fed him, and carried him wherever she went.

Whenever a gorilla baby comes to the gorilla project along the Mpassa River, a staff member adopts it until it's old enough, or healthy enough, to join the other gorillas in the forest.

Liz Pearson sleeps each night with Belinga, the feisty 6-month-old orphan who arrived with Ivindo. She has the easier job by far. Belinga is a healthy baby. But Ivindo wakes hourly in terror or pain. He's sick and miserable.

Linda sleeps little.

Her emotions grow brittle.

Since the time a visiting veterinarian said Ivindo wouldn't survive the night, Linda has fought stubbornly to prove him wrong. Together with Liz, who's in charge of this rescue project in the bush, they planned a strategy of medication and nurturing. So far, they're succeeding.

But only just.

Camille Moukala watches one of the young gorillas forage for tasty shoots. Like most people, he was frightened of the gorillas at first.

The bushmeat trade that made Ivindo a stranger to his own kind arises from subtle shifts in African culture, a culture under the dynamic influence of money, technology, and urbanization. The emerging landscape is fluid, subtly altered with each influence.

The result is sometimes baffling to visitors who expect the Western cultural snippets adopted by Africans to have the same meanings they do back home.

Men in traditional robes walk hand-in-hand on the streets of Gabon's capital, Libreville. One robed man wears a Nike ball cap. Western jingles play from constantly singing cell phones in the capital: “Shave and a Haircut” announces incoming calls.

On the train that crisscrosses the equator as it bisects Gabon, American Christmas music plays in September - the same recording, over and over, throughout the long night.

A dozen young women in blue-and-white robes and headdresses ride in the back of a pickup, clapping a complex rhythm and singing an African song as they travel past the taverns and fine French restaurants in the Quarter Louis.

Singers on television wear American hip-hop clothing and imitate the moves of American rappers. But they're singing African music.

A bride and groom walk solemnly down a path to take their vows. Pachelbel's Canon booms through a stereo. At the same time, wedding-party members break into a traditional song punctuated by a clapping beat. The bride and groom take their seats before their guests. The Wedding March plays.

Bushmeat hunting is one of the traditional practices remade under the influence of economics and technology.

Paul Aczel of the Project for the Protection of Gorillas drives through remote villages on his way back to the gorilla orphanage in the bush. A villager flags him down for a ride. Few vehicles pass this way, and it's common for Paul to carry messages or goods to and from the city.

He agrees to the lift. The man smiles, waving as he runs back to his tin-sided house. He and two friends emerge. Each carries a rifle. They are going hunting. Paul mutters curses to himself as he drives the men to a logging road a few miles away.

Hunting and the bushmeat trade are reshaping behaviors. Once cultural taboos prevented some ethnic groups from eating certain animals. A study of people in the Republic of Congo found those who previously considered gorilla and hippos sacred now included them in their diets. Researchers also determined that poor people with little access to other sources of protein most often break taboos.

Even in cities, where adequate beef, chicken, pork, and fish are available, bushmeat is popular. David Edderai, a veterinarian researcher with Veterinarians Without Frontiers, says bushmeat is often saved for special occasions.

Consider bushmeat African comfort food - city people eating the food of their village childhood.

Bushmeat is more readily available than ever as the timber industry provides roads into once impenetrable forests. Loggers also often provide transport to market for animals hunted by logging crews. Hunting can boost a logger's income by as much as 40 percent.

While in rural areas bushmeat remains the cheapest way to ensure adequate protein in a diet, in the cities of Gabon, this meat is more expensive than even the beef imported from Cameroon. Still, Gabon is believed to have the highest per capita consumption of bushmeat of any Central African nation, Dr. Edderai said.

People believe bushmeat is healthier for them, says Serge Akagah, the director of the environmental newspaper, The Shout of the Pangolin. And people often prefer the taste of a “natural animal,” comparing it to the difference between eating grocery store chicken and chicken raised in the village.

Even wildlife officials aren't immune.

Isabelle Jourdan often cooperates with members of the wildlife ministry to confiscate illegally sold primates. She works in Libreville for the gorilla project. On one trip far into the interior, they stop for lunch at a restaurant in Okandja where the only thing on the menu is monkey. The wildlife officials have monkey for lunch.

Ex-patriot Americans and Europeans may not share the hunting culture, or the taste for bushmeat, but their simple views of animals work against conservation goals. Westerners buy baby gorillas and chimpanzees as pets, fueling the continuation of such trade. A French banker brags how he has rescued two gorillas by buying them.

While Americans, who grew up with gorillas and chimpanzees as zoo animals, or as stars of wildlife documentaries, are horrified by the idea of eating our close relatives, to Africans, these are dangerous wild animals.

To farmers, wild animals aren't noble, but pests, destroying entire crops in a single night. There is a huge gulf between Western and African reality. So far, no one is quite sure how to build a bridge between them. The Project for the Protection of Gorillas is no more than a small patch on a far larger problem.

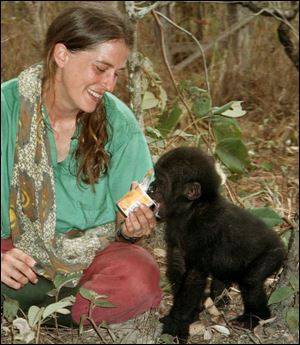

Belinga watches what's going on behind her as Linda Percy tries to give her a bottle before bed.

Linda feels her own part of that patch is a fraying failure as she watches Ivindo fade.

She and Liz take turns carrying him into the forest around camp. He could eat the leaves there, all kinds of things. But he alternates between fear and indifference during these trips.

Such an unusual reaction. So different from Kongo's first encounter with the forest, when Liz brought him to the gorilla project.

Liz Pearson drove across the savanna with Kongo lying in her lap. She placed a towel over the terrified baby gorilla. But her own malaria-fed fears were harder to shroud. She hadn't made this long drive often before. What if the truck broke down? What if she got stuck in the sand tracks that hint at this road?

The savanna buzzed with heat. It's caffeinated with nervous life. But in the truck, time crept sluggishly. Liz's fever rose. The day stretched forever, horizonless. She looked for that place where the forest begins, where the river bends, and a powerboat would dock and take her and Kongo home.

Two days earlier she took the year-old gorilla from the Port Gentil zoo on Gabon's Atlantic coast. There he spent his days lying like a rag doll on the cage floor. She shoved him in a backpack to sneak him on to a plane to Franceville, the closest city to the gorilla orphanage.

The flight was full of trouble: Kongo was gravely depressed in the backpack, biting her when she tried to comfort him. A strike at the Franceville airport forced them to stop in Libreville before heading on. The little gorilla seemed to grow more depressed, even more listless and blank than he was in the zoo.

Ahead, she saw the wall of trees at the savanna's edge.

Kongo sat up.

It was as though he smelled the forest.

As she drove closer, he grew animated. Liz stopped the truck. She and Kongo clambered out. He took a few steps, and looked up at the trees around him.

He wailed - a long, strangled cry.

“I've never heard it before or since,” Liz recalled. “It's like, ‘Where are you, my family?' But, as though he knew they weren't there.

“It was chilling.”

Ivindo won't eat.

At first, he eats bananas. Then he refuses.

They give him bread. After a few days, he won't eat it any more.

They try juice, milk, Coke - he takes them for awhile, then rejects them.

Liz and Linda begin cooking. They prepare everything they can think of to get him to eat.

Rice. He eats it. He refuses it.

Mashed potatoes. The same.

Pancakes. Same.

Yogurt, wild fruits, bread and honey, leaves, bread and jam, fresh shoots, bread and peanut butter, peanuts. Nothing lasts. Nothing works.

He's getting little nutrition. Daily he grows weaker. He takes in only rehydration fluids. Every day the same sad rejection. Linda is exhausted with the effort, and fatigued from Ivindo's night terrors.

Daylight in the bush is a wall of noise, a constant chorus of bees. Some are amber, some yellow, some are small and drawn to the eyes. Kill one, and more come, attracted by the gut smell of their sister. Put down a beer and when you lift it again a drunken bee slides into your mouth. Sit still for a moment and their wing beats rustle the hair on your arms like tiny rotors. Bees circle the head as though it's a busy airport.

Sometimes they sting. Usually they settle for provoking madness.

Linda's day winds out to the nonstop whir of the bees. Her desperation grows in the insect clamor. Over the curtain of hum and drone, she hears the boat start across the river.

Ivindo's face is a death mask, his eye sockets hollow, his mouth slack. With him in her arms, Linda races for the dock. Liz is returning from a morning with the bigger gorillas. Before Liz is off the boat, Linda is begging, almost hysterical.

“We've got to force him to eat. We've got to do this. You've got to help me,” she rattles.

Liz knows these desperate moments. She recalls the day she took Ngoma from his adopted gorilla family on the other side of the river and brought him to camp. He hadn't opened his eyes in five days. He barely moved. His lungs wheezed and gurgled when he breathed. Bubbles popped from his nose. Pneumonia was killing him. Every day a new gorilla got sick and a new one recovered. Except Ngoma. He wouldn't recover. So she brought him to camp. She wanted him with her.

Liz is packaged intensity, a set of the jaw, her angular frame packed with fierce determination.

She bent over Ngoma and sobbed. He opened his eyes. They were wide, unfocused, flitting from place to place. He looked terrified, she thought.

She'd made a mistake. She picked up the infant and returned him to the gorillas across the river, where he belonged.

He recovered there.

Liz feels Linda's panic. She knows Linda's fear. The two women talk. They come up with a plan. Every hour, on the hour, they will force-feed Ivindo.

It's a Sunday afternoon. They put a Friends tape in the VCR (run on solar power), and set alarms. At 1:30 in the afternoon, it begins.

Force-feeding is bitter work. The animal is scared. The women know he'll fight less against Liz than he would against his “mom.” Plus, they don't want to damage the bond he has with Linda.

Marshaling the last of his strength, Ivindo writhes away from Liz. She grips his head. It's this or he'll die, she thinks. There's milk in the syringe. She forces his jaws and squirts. The air is white with milk. Her face covered with it. She holds him and does it again. And again. Every hour she squirts in 16 milliliters. She squirts and blows in his face so he'll swallow. She holds his nose. He gulps it down.

Liz psyches herself - it's for his own good - fully knowing that for some animals, it's the end. They just give up. Ivindo is too near to starving for her to contemplate this long. She has no choice.

When night falls just after 6, he's still taking milk. By 7, Ivindo pulls himself up. He's not well, but he's better. He seems to have more energy.

An hour later, he vomits. Everything comes up. Diarrhea strikes. He looks worse than before, more slack, more sunken.

They begin the force-feeding again. It's getting late. Linda resolves to take over the feeding herself.

“I could take him for the night,” Liz said.

But Linda declines. If Ivindo dies tonight, she wants to be with him.

Liz can't think of a response. Both of them are desperate for him to live, but it seems so unlikely now. Liz touches the infant's head.

“Come get me if you need me,” she says and walks to her cabin.

Linda takes the syringe and milk and heads to her tent for the night. That she is long past the brink of exhaustion isn't quite clear to her. This is the pattern of her life: to work until collapse.

Jean Muofui hopes his work will help save gorillas so his children can see them. In the village where he grew up, people ate gorilla meat. Behind Mr. Muofui is Camilla Mouckala.

If Liz Pearson is the savanna of nervous intensity, Linda Percy is the forest. Her voice is quiet, her words measured, her tone modulated. In no sense is she secretive; she shows little fear of self-disclosure, but there's something enfolded in her silences. Something moving beneath the surface, like a stream out of sight but faintly audible, or the fleeting glimpse of photoluminescent life on the forest floor.

A year ago she was managing a zoo in Cameroon. She was a volunteer. When she left after 18 months, she was spent. She'd invested her own money, saw zoo employees through family crises, stitched their wounds, and helped them pay their medical bills. She cared for abandoned primates, instituted staff training, and eventually raised enough money for the zoo to operate independently for 11/2 years.

It was totally absorbing, wonderful work. It was also heartbreakingly hard.

At the end of those months, “I was shattered,” she says.

But it was a job she was born to do.

Linda grew up in St. Joseph, Mich., her father an assistant school superintendent, her mother a grade-school teacher. She wanted to be a veterinarian. She had a knack with animals.

She was the kind of kid who cried over dead goldfish. Yet she could be utterly unsentimental when required. She volunteered at a nature center where injured animals were tended. She brought some home - squirrels and raccoons - cared for them, fed them, and then put on heavy gloves and let them nip and bite in play. She was toughening them up for the wild. She never kept one as a pet. She saw each released.

Maybe the heat changed her life that day in high school. Or maybe she skipped breakfast. It might have been the flu. Whatever the problem, it sent her reeling during a career-day visit to a veterinarian's office. He made a cut. She passed out. She never knew what hit her.

After the vet visit, she spent the afternoon with a certified public accountant. She was a shy kid. Insecure. She decided on the spot she wasn't fit to become a veterinarian. She became a terrific CPA.

She worked her way up through one of the nation's premier accounting firms, Deloitte & Touche. She was a senior manager in London, on her way to becoming a partner, when she left. She didn't want to be a partner. Reaching senior manager at 30, two years ahead of her schedule, upset her balance.

“All of the sudden it was like, now what do I do? I've reached all my goals.

“There were a lot of times when I was sitting in the office at 10 o'clock at night thinking, ‘What am I doing? I'm not feeding any starving children. I'm not helping anybody.' It was the most empty feeling in the world.”

She went to Bulgaria to visit friends. At a cocktail party, she received three job offers. So she moved to Eastern Europe. The cost of living was low. She banked most of her $100,000 CPA salary. She also taught a full load of classes at a local university. In 1993 she left. She was burned out. Exhausted.

She'd always loved to travel. She headed to Australia for a few months, spent four months touring Africa, headed back to Michigan for the summer, then bought a one-way ticket to Zimbabwe, where she took a job as a guide for cut-rate Africa tours. She lived off her savings. The skimpy tour-guide pay was beer money. She hated accounting, but it got her where she wanted to go.

She was leading a tour across Africa in 1996. They needed to cross the northern tip of the Congo, then called Zaire. But war blocked the road. She was stuck in Cameroon. To kill time, she volunteered at the zoo at Limbe.

Before long, she was running it.

It can be awkward, being the white supervisor, the outsider, in an African country. Linda says she was sensitive to how it must look to the Africans, with whites so often in charge.

In Cameroon, when people tried to sell animals to the zoo, Linda didn't lecture them on the law, or the risk to wildlife. The Cameroonian employees did the talking.

“I didn't like this image of the white man coming and saying, ‘You do this and you do that.' I kind of stayed in the background.”

There's little question that the history of conservation in Africa has been a matter of whites telling Africans how to manage wildlife. For whatever good has come from decades of white-driven conservation, the baggage created by the arrangement is considerable - and some would argue not always in Africa's best interest, or in the best interest of the species in question.

Some consider the 1989 ban on the ivory trade as one instance of heavy-handed Western interference.

“You can talk about a kind of imperialism. You can talk about a total lack of realism. You can talk about what I call eco-apartheid,” says Eugene Lapointe, a leader in international environmental issues. Mr. Lapointe served as general secretary to the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species from 1982 to 1990. This body decides on limits to trade in a variety of plants and animals around the world. And it was through this body that the total ban on ivory sales was enacted by member nations.

Mr. Lapointe says that pressure to ban ivory sales sprung from Western environmental organizations' willingness to reduce a complex issue to a simple, emotional formula. The organizations gained a flood of dollars from donors touched by the elephants' plight. They sacrificed good conservation.

“What started as a conservation objective just became a big political and financial objective,” Mr. Lapointe says. Instead of raising money to save elephants, some organizations “used the elephants to raise funds.”

But groups such as the World Wildlife Fund, which supported the ban, say the ban was the only way to bring poaching to a halt.

“Look at the facts we were facing at the end of the 1980s. We'd lost half of all elephants in about 10 years due to poaching,'' says Ginette Hemley, vice president for species conservation at the World Wildlife Fund. Kenya and Tanzania lost 50 to 80 percent of their elephant population, she says.

But opponents of the total ivory ban said it was unfair to countries that controlled poaching and maintained large elephant herds. In Namibia, Botswana, and South Africa, hunting was necessary to keep herd size under control, says Mr. Lapointe. Ivory sales from culling provided money for wildlife management.

Instead of supporting a flexible solution, which would allow nations with poaching problems and nations with too many elephants to each address their needs, a one-size-fits-all solution was imposed, says Mr. Lapointe.

“Everybody recognized there were some elements of unfairness to those three countries,'' says Ms. Hemley of WWF. “But there was a possibility that illegal ivory could be laundered through those countries. The trade control seemed pretty good, but the systems were too new to feel confident that there wouldn't be laundering.''

Further, she says, any ivory trade could stimulate the trade in the rest of Africa.

A partial ban would be like “trying to carry a bag of water with holes in it,” says Heather Eves, a wildlife biologist and director of the Bushmeat Crisis Task Force.

But Mr. Lapointe says such a solution fails to support successful wildlife management in Africa. Instead of a blanket ivory ban, Western nations should have acted to strengthen trade barriers and environmental efforts.

“This is an incredible imposition of values for Europeans and North Americans. To see an elephant on television is amazing. The reality in Africa, if you have too many elephants, is quite different. We certainly cannot impose those kinds of views on the African people.”

Dr. Leonard Usongo is a field biologist and area manager for the World Wildlife Fund in Cameroon. This spring, he attended a meeting of primate researchers in Chicago. The bushmeat crisis was a prominent theme. By the third day, he was dismayed by his Western colleagues arguing policy for Africa.

“I feel so frustrated when I attend these meetings. I live in the field. I see things on a day-to-day basis.”

While many conservation groups agree with Dr. Usongo's ideas about the bushmeat problem - the need for logging companies to control hunting among their workers, the necessity of educating decision makers - the perspective got little airing among primatologists at this meeting.

Poverty, lack of education, lack of alternative income, and lack of incentives for local people to control hunting are at the root of the problem, says Dr. Usongo. But he heard few people raise these concerns.

Western researchers have had a field day in Africa: “Most of the time, they do their research, they do fancy research work, and then they go. What's left in the end? Nothing. They have done the research work and they have not changed the patterns of the country.”

But Ms. Eves says those practices have been changing over the last two decades.

Calling Dr. Usungo's perspective “valid ... and not uncommon,” she says, “It requires some qualification.

“There are Western types, ex-pats, who go in, do their little research project, and never even leave a copy of their work. But many are working in collaboration with African counterparts ... and are committed to leaving their positions to those African counterparts.

“I do think it's important to have an African perspective,” she says. “I don't think you'll find a conservation organization active in Africa today that doesn't have as one of its main priorities capacity building - making sure that it's not all just ex-patriots.”

At the Chicago conference, a video the first evening showed researchers restoring orphan chimpanzees to the wild. The film, full of interviews with European experts, encapsulated the problem.

“Where were the Africans?” Dr. Usongo asks. “Just carrying the backpack or driving the boat.”

But there is a growing African voice in conservation. Africans manage the World Wildlife Fund office in Gabon and make up most of the staff. Africans publish the Gabonese conservation newspaper, The Shout of the Pangolin.

Its editor, Serge Akagah, also leads a nongovernmental organization called Friends of the Pangolin.

Inevitably, the views of Africans in conservation are sensitive to the needs of African people.

“There is oppression on bushmeat, but the people must survive,” Mr. Akagah says. “If we say don't hunt, what alternatives do we propose to them? The main objective is the conservation of human beings.”

It can be obvious who the bushmeat hunters are. In September, some 50 men from Equatorial Guinea camped in Gabon's central region killing everything that moved for market. But often, it's not so clear.

“If you have one hunter kill two animals, it's a good hunt. He can eat one and sell the second. In this case, it's difficult to say who is and who is not a bushmeat hunter,” Mr. Akagah says.

Numerous studies suggest that even hunting at this low level may not be sustainable for animals with slow reproductive cycles, where offspring are few, and time between births is long.

Martin Heja, chief director of Shout of the Pangolin, says for the hunter with two animals, that second kill is important.

“This is money to buy soap, to buy clothes, to send children to school. If there was an alternative - but what is it? These people have children. These people have families. (People) say hunters should stop, but they don't offer a proposal. That's the main problem,” Mr. Heja says.

It's not that the two men are indifferent to bushmeat hunting. Far from it. Mr. Akagah says it is Central Africa's No. 1 environmental problem. Educating Central Africans about bushmeat is one of the organization's primary goals.

They just want answers that include the needs of African people in the equation.

Leaders in the Project for the Protection of Gorillas in Gabon are all white.

“Black people will lead these organizations someday,” says Jean Muofui, one of four Gabonese men who work in the project.

“It's the idea of whites, but we should have thought of it because it's important work.”

“I really believe in what we're doing,” the 23-year-old says. Every day he goes into the forest with the gorilla orphans and follows them as they forage for food. He takes the place of the missing mothers by carrying the little ones who normally would ride on their backs. It is work both black and white staff members do.

At his home village, people find the whole notion of his work amazing.

“It's hard to believe. Even for me. I grew up with the belief that gorillas are really mean. Usually people don't know what to think, but once I explain, I think they understand. I know my family understands that if we save gorillas, our children will see them. My family encourages my work, but they say, ‘Be careful.'”

Some of the other workers have only seen apes on television, but Jean kept a baby chimpanzee as a pet at one time. He saw gorillas when hunters brought them home. And he's eaten gorilla.

“I feel sorry I ate gorilla before,” Jean says. “They are just like children.”

Ivindo is clearly as close to being Linda's child as is possible. It's nearly midnight, and she's beside herself.

She tried to force-feed Ivindo on her own. But he only seemed to get worse. He's anxious and stressed. All her efforts for all these weeks seem to be collapsing in her arms.

She's crying as she gathers the failing infant and runs into the night. She never sees the billion stars that crowd the African sky. She doesn't hear the racket of the crickets. She doesn't think about the things that live in the forest encircling the campsite.

She raps at Liz's door.

“I can't do it,” she blurts.

“You've got to help me.”

TOMORROW: The gorilla gamble.