COMMENTARY

Seaman floats theory of what really sank Titanic

6/2/2014

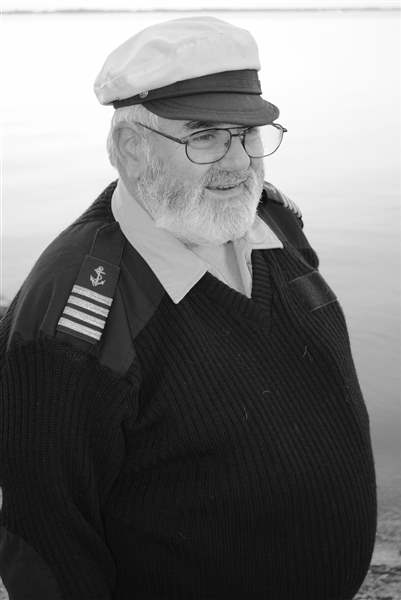

Brown

Walton

It was in the middle of a winter for the ages — you remember January, right? — and David Brown was going stir crazy at his home in Port Clinton.

Brown

His mind wandered to a favorite topic of his: the fate of the RMS Titanic. He had an epiphany: A furnace stoker named Frederick Barrett unwittingly sealed the Titanic’s fate.

Mr. Brown, with his stout build and salt-and-pepper beard, looks like a sea captain, which he is. Captain Brown also is an instructor at the Maritime Academy of Toledo and the author of two books on the mysteries and myths surrounding the most famous shipwreck in history.

Snowbound and bored, he went back to his voluminous research — rereading, rehashing, recalculating. He looked yet again for something he might have missed, something that might further separate fact from Hollywood’s notions of the Titanic.

Poring over his charts and deck plans, painstakingly recreating the time line of events that awful night of April 14, 1912, he saw it. Stoker Barrett, one of the strong-backed grunts in the belly of the Titanic, had consigned the great ship to its place in history when he opened a 10-inch bilge valve. He had been sent to do it to reconfigure the bilge pumps, but the valve instantly began filling the boiler room with water and further aggravated the bow’s downward tilt.

Striking the ice, Mr. Brown is convinced, was not catastrophic enough to send the Titanic 2½ miles to the bottom of the Atlantic. He debunks the notion that the iceberg’s gash in the Titanic’s hull doomed the ship. Water did not rise over any bulkheads, he believes, until human error intervened.

“If [Mr. Barrett] had been an American, he might have questioned the order and closed the valve again right away,” Mr. Brown says. “But being a Brit, he followed his orders.” No counter-order came, and the massive gush of water continued.

Mr. Barrett made no mention of the valve to investigators after the tragedy. He had run for his life, he said, escaping through a lowering watertight door, and survived the wreck.

Mr. Brown thinks Mr. Barrett bent the truth — or at least wasn’t forthcoming about what he knew — for an obvious reason: He didn’t want to be known forevermore as the man who caused the tragedy.

Until the moment the valve was opened, Mr. Brown says, the Titanic was not sinking. Had that singular act not occurred, the great ship could have stayed afloat until help arrived, saving most or all of the 1,500 souls who died when the Titanic foundered.

Is he sure of that?

“History does not reveal its alternatives,” he notes. Pressed for a yes or no — would the Titanic have survived? — he nods affirmatively.

“I did not figure [all] this out until this winter, when icy roads made leaving the house impossible.,” Mr. Brown says. “I returned to Titanic to kill my blizzard boredom.”

His explanation of what doomed the Titanic is complex and laced with the jargon of men who went to sea in those days and steered their ships by the stars. But his beliefs are rooted in mathematics and modern thought. They upgrade the tarnished reputation of the ship’s master, Capt. Edward J. Smith.

Rather than ignore the iceberg peril of the North Atlantic, the captain was quite mindful of it. He instructed his officers to be especially vigilant that night. He carefully plotted ice warnings coming in from other ships and made at least two course adjustments.

In Mr. Brown’s view, myth once again overtook fact. Captain Smith, who went down with the ship, became the victim of a story line that has often made him out to be a fool.

Mr. Brown is convinced that had the accident occurred, say, seven years later, on April 14, 1919, the lessons learned from the premature abandonment of warships in World War I would have saved the Titanic. “Lusitania. Same thing. Brittanic. Same thing. Knowledge gained would have kept them afloat,” he said.

Mr. Brown is a skilled boatbuilder who for years held a master’s license for Great Lakes vessels. He once told an interviewer: “There aren’t many people who can wring as much fresh water out of their socks as I have.” The Titanic and teaching at the maritime academy remain his passions.

His conclusions are especially relevant while the Titanic exhibition continues at Imagination Station downtown. It will end Sept. 21.

There have been two Titanics, he says: the real ship and the mythical one that still sails in our imaginations. “The truth isn’t easy for the average person to understand,” Mr. Brown says. “The myth is infinitely easier on the brain. People like to take the path of least resistance.”

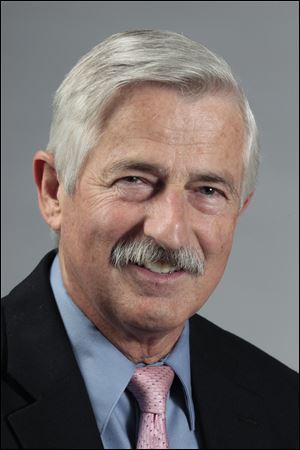

Thomas Walton is the retired editor and vice president of The Blade. His column appears every other Monday. His commentary, “Life As We Know It,” can be heard each Monday at 5:44 p.m. on WGTE-FM 91.

Contact him at: twalton@theblade.com